A couple of years ago I read a fascinating article in Foundation Review by TCC Group’s Paul Connolly called ‘The Best of the Humanistic and Technocratic: Why the most effective work in philanthropy requires a balance’[1]. The article addresses something that increasingly worries me the longer I work in philanthropy: that the growing trend towards rationality will overwhelm the compassion and boldness of the civil society sector. Although I still worry that the scale is currently tipped too heavily towards the technocratic, the article’s emphasis on a balance between the two did calm my nerves.

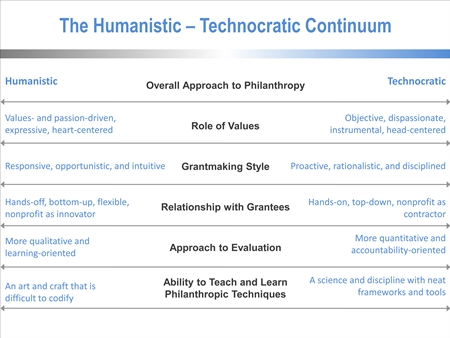

Among other things, the author points out that these two approaches are on a continuum rather than in opposition to each other, as recent counter-productive ‘either-or’ debate has tried to suggest. Connolly encourages the philanthropic field to accept the tension between the two. The chart below, reproduced from the article, ably captures the tension. If you have not read the article, I highly recommend it.

The humanistic-technocratic continuum

This humanistic-technocratic continuum frequently comes into play in one aspect of my work. I call it the ‘foundation programme officer’s dilemma’. On the one hand, grantees would like us to give them maximum flexibility (general operating support, multi-year grants, etc) and support their work without imposing our own agenda. On the other hand, foundation management and boards want to see focused strategies, logic models or theories of change, clear indicators of progress, measurable outcomes and definitive impact. The pressure comes not only from management/board on the one side and grantees on the other. Various external forces – watchdog groups, consultants, experts, philanthrocritics and others – call for one or the other. Sometimes the same people or organizations call for both at the same time.

Naturally, the simplest way to get a desired result is to control the process. I’ll never forget struggling with that when working at the Eurasia Foundation in Ukraine in the 1990s. One of the ways we were supporting democratic development was through grants to NGO resource centres – although structured as project grants, they were essentially for general operating support. When the word came down from our management that we needed to raise non-USAID funds for our work, we had to ‘package’ our NGO resource centre support into a ‘programme’ (I think we called it the ‘Strengthening NGO Resource Centres in Ukraine Program’). In the process of honing our anticipated results so that we could present it as an investment opportunity to others (including the Mott Foundation, where I now work), we ended up narrowing the scope of their grants, defining the technical assistance they’d receive, delineating at least some of their programming, and prescribing how they’d organize their networking and capacity-building activities.

To be fair, there was a lot of benefit to that: it became clearer, even to us, what we were all trying to achieve. We became better able to make the link between the grants to the NGO resource centres and the Eurasia Foundation’s organizational goals. Furthermore (although in retrospect we could have done this much better), we did ask our grantees what they thought would be useful to them. We should have gone a step further and asked their clients.

Strictly speaking, that wasn’t a programme officer dilemma – I was a director at the time and the ‘pressure from above’ was less from my own management than from the imperative of raising funds – but a similar dilemma has played out many times in my career as a programme officer.

A more recent case in point: a couple of years ago at Mott we adopted a revised Civil Society Program plan. One of the organizations we were funding, whose mission falls under a broad grantmaking objective that we still hold, no longer easily fitted into the more narrowly defined strategy that was part of the new plan. It was hard to directly tie the grantee’s work to one of our new indicators of progress for that programme objective. I told the organization that I would not renew the one-year general operating support grant we had been awarding for the previous four years.

Now, there were other factors in my decision, such as a conviction that the grantee was at a point where it could earn more revenue to cover core costs, but I cannot deny that the matter of ‘fit’ with our progress indicator had an influence. Before you judge me too harshly, though, the rest of the story is that I invited a much larger project grant for a period of 16 months and later a renewal of that for another 22 months – and the organization was able to convince another foundation to match our funds. It just so happens that the project was for work that they had been wanting to pursue but had not yet been doing, work that I also am very passionate about, and that fits our progress indicator. I know, because I developed the indicator. But I still have to report on it to our management and board.

Did I limit the grantee’s flexibility? Yes, in the short run. Was it a bad thing? Maybe – time will tell.

Where does the technocratic end and the humanistic begin?

What does this all have to do with the above chart? The tension between just providing resources and attaching strings to those resources is as old as parenting, after all. However, it seems to me that at first glance, for the two cases I illustrated above, I let the technocratic side fully take over. Looking at the chart again, it appears that in both cases my grantmaking style was proactive and rationalistic, and my relationship with grantees ended up being hands-on and top-down. I limited the grantees’ flexibility in the name of being ‘strategic.’

But on deeper analysis, I think there was some humanistic involvement. Although a significant driver of my decisions was strategic alignment with the imperatives of my organization, I feel that in both cases I was driven by values and passion, opportunistic (after all, my actions led to more resources for the grantees) and even intuitive (I had no hard evidence that new approaches would be more effective). Which illustrates Paul Connolly’s point – that what’s important is to balance the two.

Whether I found the right balance is something that only the grantees, or perhaps evaluators, can answer. But I believe that my grantmaking – which to me still seems more of an art and craft than a science – is of better quality when I’m aware of the tension and know where I am on the humanistic-technocratic continuum. No matter what, grantmaking still involves exercising judgement. One other important lesson to draw is that, as a grantmaker, I must not lose sight of the effect of my humanistic and/or technocratic intervention on the grantee, who suffers most the consequences of my programme officer dilemma.

The theme of this issue, ‘Philanthropy in a Changing World Economy’, seems distant from my dilemma – but maybe not. The economy is becoming ever more interdependent. Philanthropy is set to take on more global challenges, work across borders, and tackle very large, ‘wicked’ problems. In a world of ‘big data’ and rapid communications, with market thinking and business approaches becoming more pervasive in philanthropy, foundations are indeed rethinking their role and coming up with new ways of working. But we are still people, and we must not lose sight of the humanistic side of the continuum to complement the technocratic – or vice versa, of course.

Nick Deychakiwsky is a programme officer at the C S Mott Foundation. Email nick@mott.org

[1] Paul Connolly, in Foundation Review, Vol 3 Numbers 1-2, 2011, pp120-36.

Comments (0)