New Philanthropy Capital’s (NPC) new report, 10 Innovations in Global Philanthropy, aims, say its authors, to bring more money into philanthropy and to see it spent more effectively. As its subtitle, ‘concepts worth spreading to the UK’, suggests, UK philanthropists are its main intended audience. Alliance asked observers from around the world what potential they see for these ideas in their country or region and how much adaptation they would require. But are innovations the whole of the answer? As Katherine Fulton, Gabriel Kasper and Justin Marcoux of the Monitor Institute point out, such a list drawn up 10 years ago would have covered pretty much the same areas. Is something besides new ideas required?

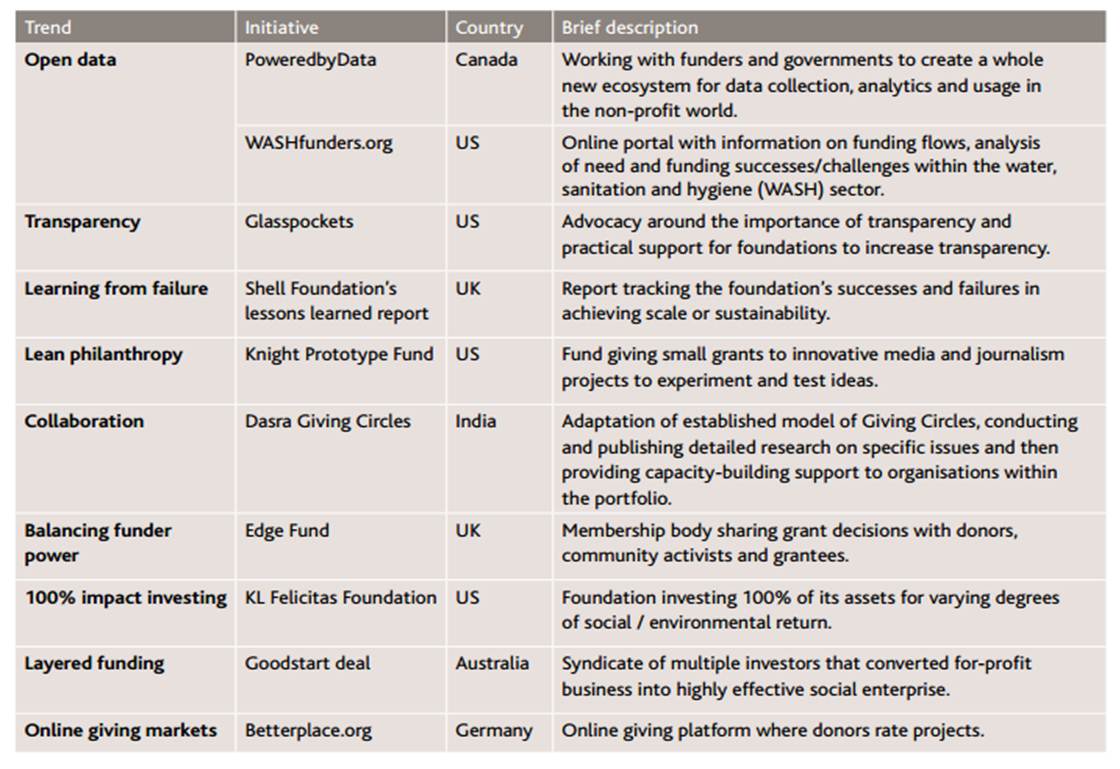

It is worth noting for the sake of clarity that the 10 innovations are grouped under nine themes (see table below). While some of our respondents talk about the specific initiatives highlighted in the NPC report, others talk more generally about the relevance of the themes in their part of the world.

Who likes what?

First of all, the ranking: what did most people like? Given that some people chose just one innovation and some mentioned half a dozen, there is nothing scientific about this, but here goes. Top of the list came Glasspockets, under the transparency label, with five people mentioning it. Next came the Shell Foundation’s learning by failure report, with three mentions, while all the others had a couple of mentions each.

What did the different respondents mention?

- Maria Chertok, Russia: Glasspockets, Edge Fund, Knight Prototype Fund

- Jennifer Gill, New Zealand: Glasspockets

- Halima Mahomed, South Africa: collaboration, Glasspockets, Edge Fund

- Cathy Pharoah, UK: WASHFunders.org

- Pieter Stemerding, Netherlands: transparency, learning from failure, collaboration, new ways of funding (layered funding, 100% impact investing, online giving markets)

- Carolina Suarez, Colombia: all innovations relevant, especially open data, transparency, learning from failure, lean philanthropy and layered funding

- Clare Woodcraft, UAE: learning from failure, 100% impact investing

- Tao Ze, China: PoweredbyData, Betterplace.org

Glasspockets: top of the pile

Maria Chertok of CAF Russia is one of those who particularly likes the Glasspockets idea: ‘transparency is always an issue with foundations, and Russia is not an exception.’ Glasspockets is also top of the list for Jennifer Gill of ASB Community Trust in New Zealand. She sees it as serving the double function of creating transparency and providing a basis for greater sharing of information. As many donors, new and established, are effectively working alone in both Australia and New Zealand:

‘A southern hemisphere Glasspockets has the potential to span the divide between Australia and New Zealand, and within our countries, bringing grantmakers closer together. It would be a leap into the 21st century for both countries.’

Transparency is also rated highly by Carolina Suarez of AFE (Association of Corporate and Family Foundations) in Colombia, while Pieter Stemerding of the Netherlands-based Adessium Foundation stresses the need for transparency both about funding and about the impact of the money spent, which he describes as ‘an ongoing concern’.

Open data

NPC’s report includes two open data innovations, PoweredbyData and WASHFunders.org. There is a hunger for data in the philanthropy sector, says Cathy Pharaoh of the UK’s Centre for Charitable Giving and Philanthropy. However, without guidance on how to use it, data won’t be much use. This, for her, is what WASHfunders provides.

‘WASHfunders focuses on one area but it is a model which could be easily adapted to many other issues. Its great strength is that it pools experience and information from many sources, enabling critical dialogue and evaluation as well as potential for collaboration, and avoidance of duplication.’

Tao Ze of the China Foundation Centre (CFC) believes that PoweredbyData, along with onling giving platform Betterplace.org, is the innovation most likely to find a receptive audience in China – both because the initial public offering of Alibaba shares has captured the public imagination and because

‘Top foundation leaders believe that data and the internet will rebuild the ecosystem of the Chinese philanthropy sector.’

As he points out, moves towards greater transparency are already well in hand in China through CFC’s transparency index (favourably mentioned in NPC’s report).

Platforms for data sharing are being developed in Colombia, notes Carolina Suarez, including one by AFE itself, but the biggest challenge is to get people to update the information. ‘They have to see the platform as a strategic tool in order to create an ecosystem.’ In Colombia, she says:

‘Foundations are constantly accused of lacking transparency. We frequently witness cases in which some entities called “foundations” are involved in mismanagement of public funds or corruption … while initiatives for the promotion of transparency and accountability are worth nothing.’

Learning from failure

‘The idea of learning from failure resonates hugely with Emirates Foundation,’ says Clare Woodcraft. She goes on:

‘Our model of venture philanthropy is all about learning from failure and assuming a certain level of failure just as a venture capitalist would.’

If something is not working, ‘we stop, assess, revise and then redesign a programme’. It’s an approach that has been ‘heavily influenced’ by the Shell example used in the NPC report.

Pieter Stemerding agrees that learning from failure is something foundations should always be doing, but Maria Chertok has reservations. While she sees the virtue of admitting – and learning from – mistakes, she sees the example NPC gives as problematic because she believes Shell Foundation ‘disclosed their failure to underline their success’. Still, in principle, she says, the notion of talking about failure is valuable and one that Russian donors have yet to take on.

What about collaboration?

Halima Mahomed of TrustAfrica sees collaboration as a key area for innovation in Africa. She notes, however, that:

‘Informal issue-based collaborations are not new in Africa … For instance, village members pooling funds to support a child’s education is a feature of communities in so many parts of the continent and has led to opportunities for many, many children that would never have been available otherwise. In fact, the value and impact of this ongoing form of giving is completely discounted.’

But she also recognizes the limitations of issue-based collaborations. While they are valuable, thematic interventions need to be placed ‘within a more integrated understanding of the complexity and multiplicity of issues and contexts’.

Pieter Stemerding also emphasizes the need for collaboration to avoid the ‘solo action or silo thinking’ which reduces the impact of philanthropy.

New ways of funding

For Stemerding, layered funding (Goodstart), 100% impact investing and online giving markets can all be seen as ‘new ways of funding’. Another new way is ‘lean philanthropy’. The Knight Prototype Fund attracts Maria Chertok not so much because of its ‘leanness’ but because of its willingness to invest in experiments – a feeling echoed by Carolina Suarez, particularly in a region which has seen withdrawal of overseas bilateral funding, coupled with the tendency of many local funders to play it safe, says. Such a fund could give NGOs the means to experiment, she says.

Suarez also mentions Goodstart, the layered funding initiative. ‘To build peace in our country, we need to bring together our knowledge, capacities, skills and funds.’ Initiatives like this represent ‘a good opportunity to learn how to design a successful collaboration across sectors’. Maria Chertok likes the Edge Fund idea (balancing funder power), another new approach to funding:

‘Though the issue is not even on the agenda of Russian donors, it’s an important one, because lack of beneficiaries/communities involvement in funding decisions is apparent.’

Mission-related investment (100% impact investing), says Clare Woodcraft, is the ‘elephant in the room when we look at funds under management in the sector and funds allocated to programmes’.

‘Too often the real financial value in foundations lies in their endowments and yet all the focus of attention is on actual programme delivery. There is a huge opportunity for foundations to become much more innovative in how and where they invest driving direct social change through the sheer size and scale of their investments.’

How easy will it be to adapt?

How easily could the innovations be adapted? In terms of the mechanics, Jennifer Gill believes her southern hemisphere Glasspockets would be relatively straightforward to set in motion since ‘New Zealand has a well established, national database of sources of funding (FundView)’. The challenge, she believes, ‘will be to find funders prepared to see the value of and invest in open data for both the grantmaking and grantseeking sides of the equation.’

Neither Pieter Stemerding nor Cathy Pharaoh feel there would be any problem ‘naturalizing’ the innovations. Pharoah sees the WASHfunders model as readily adaptable to the UK. Though its focus ‘would need to be extended to domestic issues, and it would need to draw on UK data sources’, there is already a great deal of information available on local needs. A good starting point, she feels, ‘might be homelessness or access to legal advice.

‘Finding funding for innovations in data and research “brokerage” is always a challenge in the UK, because many funders and donors hesitate to invest in building the philanthropy infrastructure, despite its huge potential to increase effectiveness in use of resources.’

For Tao Ze, time is the key factor. In his view, Chinese foundations ‘need another two to three years to be ready to implement’ the innovations he sees as most necessary. Maria Chertok echoes this: adoption of many of the innovations would require a culture change in Russia, which takes time.

A question of attitude

For Clare Woodcraft, among others, the major obstacle to a culture of learning from mistakes is attitude: ‘We still see aversion to even mentioning the word “failure” so tend to focus on “lessons learned” or “institutional learning”.’ Carolina Suarez laments that ‘too many egos surrounded the philanthropy network’. One of the main difficulties, she says, is to share information and recognize that not all philanthropic interventions are successful.

Halima Mahomed also admits that transplanting the innovations might not be a simple matter, for three reasons:

‘The environment/context within which we operate is so very different on the African continent; the developmental stage of formalized philanthropy and of the philanthropy infrastructure is still relatively nascent; and non-formalized giving is often so intertwined with formal giving.’

Pieter Stemerding wonders more generally ‘whether innovations (and new hypes) are needed to move the sector or is it about (more structurally) changing/adjusting the culture/underlying values in the sector?’

What’s missing from the list?

Bearing in mind the differences local circumstances make to the practice of philanthropy, we also asked respondents if there was anything they would add to NPC’s list. Mirror funds, suggests Jennifer Gill. Pioneered in the philanthropy sector by GuideStar in the US, mirror funds allow individual donors to follow the donation choices made by a larger or more experienced donor, say the Gates Foundation, effectively piggybacking on the expertise of that foundation.

‘In a small country with a relatively well connected philanthropic sector and an emerging group of new individual donors, mirror funds make lots of sense.’

‘I would have included Spacehive,’ says Cathy Pharaoh, ‘a crowdfunding initiative aiming to raise local funds for civic spaces.’

‘Local crowdfunding has fantastic potential to bring local donors, funders and interests of all kinds together to create better local facilities, and build a shared sense of community identity and purpose.’

Clare Woodcraft cites social impact bonds as another promising area, but she feels that the vocabulary needs to change:

‘Too often it’s too complex or alienating to talk about mission-related investment or social finance bonds and much easier to talk about how many grants we make. But if the sector is to professionalize, and create real solutions to wicked problems, this is where we need to be headed.’

The Monitor Institute team have several suggestions. Their first is ‘high-risk, high-reward philanthropy’ to pursue breakthrough social change.

‘As the strategic philanthropy movement has swept across the field, funders have aligned their programmes and grantmaking with carefully designed theories of change to produce clear and quantifiable results. In doing this, they have gravitated toward safer and more established programmes.’

Lean philanthropy is just one method for experimenting with transformative new ideas, they say.

Another issue for the Monitor Institute is how funders find new ideas or stay abreast of relevant trends. They cite the Rockefeller Foundation, which uses its grantees to help with scanning, and provides additional funding to a group of ‘searchlight partners’. Others are investing in ways to comb through massive amounts of ‘big data’ and social media information to see what communities are buzzing about.

They also mention foundations exploring how they can leverage their non-monetary assets to affect change: their convening power, their voice in advocacy or public policy issues, using their reputation to influence others to give. Here they give the example of the Dodge Foundation’s use of Kickstarter to promote and recommend local art projects.

Finally, Pieter Stemerding makes a wider point:

‘The innovations seem to be more focused on the process of giving/investing (ways to give, transparency about giving, lessons from giving) than on impact/effectiveness of giving. The former is indeed important, but strengthening the process of giving/investing is only one aspect of increasing the effectiveness of the sector. The effectiveness and impact of the money spent is a huge challenge which should be an ongoing concern.’

An artificial separation

Implicit in many of the responses is the idea that many of these innovations are not separable. Discussion of open data often leads on to transparency and so on. Fulton, Kasper and Marcoux of the Monitor Institute take this a step further and suggest actively bringing these innovations together, seeing their ‘potential to intersect, combine and build on one another to create even larger changes in the field’.

‘For instance, combining the two trends “open data” and “collaboration” could lead to a fundamentally new way of bringing people and organizations together to use data and data visualization techniques to make better, more informed decisions.’

Another potential intersection, they feel, ‘is between giving markets, open data and transparency’.

‘Giving markets like Donors Choose and Give Directly are already connecting donors to individuals. With more robust markets, better transparency and the right data, it is likely that more donors (of all shapes and sizes) will connect directly to people and causes they care about, creating lasting changes in both the way philanthropy is done and who is involved in doing it.’

Innovation and novelty

Some of these innovations or similar ones are already occurring, as our respondents have noted. Carolina Suarez cites AFE’s work on open data in Colombia; Emirates Foundation has taken on the culture of learning from mistakes; while the Monitor Institute team see the relevance of NPC’s list to the US, they feel that many of the ideas are already being implemented.

But innovation is not the same as novelty. Halima Mahomed reminds us that innovation need not come from something entirely new. It might come from the recombination of existing elements in a new and imaginative way. She cautions us not to lose sight of potentially innovative elements of existing means of giving:

‘I worry sometimes about the focus on innovation when it is placed in a context that disregards age-old mechanisms that have been ignored or discounted. I think that there is enormous potential to look at existing mechanisms and channels of giving on the African continent that don’t fit into formal or external definitions of philanthropy. For me what is missing is a better understanding of what lessons and innovations are contained within these existing practices.’

The next question …

The Monitor Institute team, meanwhile, open up a new line of debate. The initiatives themselves ‘are certainly new and creative’, they note, but the underlying themes – transparency, the need to learn from failures, the use of all of a foundation’s resources, the need to fund experiments – have been discussed in philanthropy circles for a good long time. Moreover, the specific innovations listed by NPC are not the first examples of their kind.

‘The Ford Foundation used layered funding back in 1981 to seed the Grameen Bank, CDFIs have been doing 100 per cent impact investments since the mid-1990s, and giving circles have been around for decades.’

The inescapable conclusion is that having an idea is not enough. ‘Why have these innovations, some created decades ago, spread so slowly?’ they ask. Although this was not the question addressed by NPC’s report, Monitor Institute would ‘love to see more consideration of what it takes for innovation and new thinking to take hold in philanthropy’.

Perhaps part of the answer lies in what our respondents say about impediments to the spread of NPC’s innovations in their own regions: attitudes need to change. As Maria Chertok puts it, how does one get the philanthropy community to ‘own’ the need for these innovations? Having led your horse to water, how do you get it to drink?

Alliance would like to thank the following for contributing to this article:

- Katherine Fulton, Gabriel Kasper and Justin Marcoux, Monitor Institute, USA

- Jennifer Gill, ASB Community Trust, New Zealand

- Halima Mahomed, TrustAfrica

- Cathy Pharoah, Centre for Charitable Giving and Philanthropy, UK

- Maria Chertok, CAF Russia

- Carolina Suarez, AFE, Colombia

- Pieter Stemerding, Adessium Foundation, Netherlands

- Clare Woodcraft, Emirates Foundation, UAE

- Tao Ze, China Foundation Centre

Comments (0)