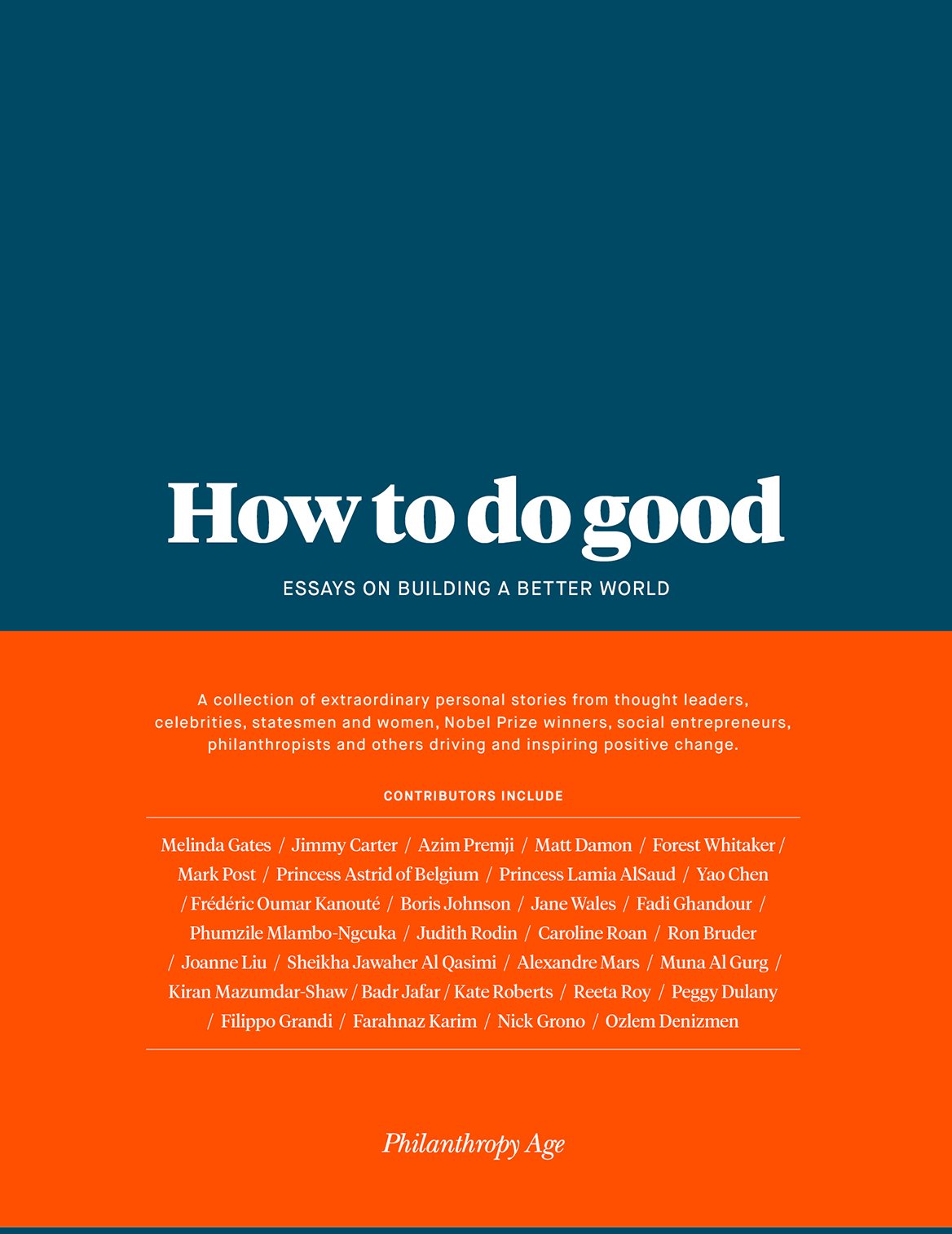

‘How to do Good – Essays on Building a Better World’ is a recently published book that gathers testimonials from a number of prominent philanthropists around the world, but also from actors (e.g. Matt Damon), political leaders (e.g. Jimmy Carter) and sportsmen (e.g. football player Frédéric Oumar Kanouté). Many of them live in English-speaking areas of the world, but there is a plurality of viewpoints.

The book’s core argument is pretty straightforward: Everyone is free to act for the common good; therefore everyone can do their bit and make a difference, albeit modestly.

The book’s core argument is pretty straightforward: Everyone is free to act for the common good; therefore everyone can do their bit and make a difference, albeit modestly.

Yet this déjà vu idea in the philanthropic microcosm still needs strong-minded supporters and unyielding advocates in our rather selfish epoch. At least should it be so until everybody becomes (or effectively intends to become) a philanthropist—i.e. not necessarily someone who writes checks but who actively takes care of their fellows on this Earth.

This blog post stems from a French standpoint. The perspective of extensive citizen’s involvement has admittedly not been quite common in France’s long political history, neither is it widespread today, despite noticeable changes in the general mentality over recent years.

Helplessly witnessing a declining role of the State—which was formerly omnipotent and affluent but nowadays more fragile and penurious—French people are being increasingly encouraged by public authorities to take an active role into funding a growing number of public interest fields, ranging from the arts to education and research, or from preserving heritage monuments to fostering environmental conservation.

It should of course be acknowledged that the legal and administrative framework for establishing private foundations has been greatly softened – namely through a purposeful legislation passed in 2003 – and that fiscal deductibility of charitable gifts has been heightened—to the extent that France now enjoys probably one of the most advantageous fiscal status for households giving, where gifts can be deducted from the amount of taxes due and not the taxable income as in most countries.

Giving by individuals has been steadily increasing over the past 20 years, up to around 4.5 billion euros. Volunteering is widespread among between one fourth and one third of the adult population (estimates vary), and over 1.3 million lively associations are registered to this day.

But a decade of incentives certainly does not suffice to overcome centuries of mutual distrust between taxpayers and the State. The latter had traditionally been jealous from every sort of counterweights, including all forms of endowments – long before the so-called ‘absolute monarchy’ and well beyond the advent of the Republic – while the former had been gradually discouraged to take part in handling issues of the community outside of the political realm, and ended up counting on their sole own merits – this reflex can arguably be seen as the dark side of a ‘meritocratic’ system that praises individual success while downplaying the community’s indispensable role.

The ‘giving-back’ moral imperative that is so prevalent among those who prosper in many English-speaking areas seems to remain foreign to French sentiment. But things are changing for real. Many of the wealthy are actually very generous. Our research enquiries show that they just do not speak up enough about their good deeds, probably by fear of displaying their affluence to resentful crowds, and also because a majority tends to consider that ‘Good does not make any noise; noise does not do any good’.

In this context, the ‘How To Do Good’ tour stopped in Paris after a series of stages in Oslo, Stockholm, The Hague, Brussels, and before a home-run in London and New York. For French audiences, this original event gathering together practitioners of the charitable sector, philanthropists and researchers, driven by a testimonial approach, was a prime opportunity to recall this simple truth: Philanthropy is not a club’s monopoly. Everyone goodhearted can join and amplify this upward movement.

This truly echoes what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., said in a 1968 sermon:

‘Everybody can be great, because everybody can serve. You don’t have to have a college degree to serve. You don’t have to have to make your subject and your verb agree to serve. You don’t have to know about Plato and Aristotle to serve. You don’t have to know Einstein’s “Theory of Relativity” to serve. You don’t have to know the Second Theory of Thermal Dynamics in Physics to serve. You only need a heart full of grace, a soul generated by love.’

Charles Sellen is a Doctor in Economics, specialised in Philanthropy.

About the book

Published by London Wall Publishing

Price £40

ISBN 9780993291784

Order here

Comments (0)