Few things make so deep or immediate an impression, or can dramatize the human condition so forcibly, as a piece of art, yet it’s an area where funders are reluctant to tread. We asked a number of funders who do support the arts and a number of arts organizations and artists from around the world to answer just one question: ‘Why should philanthropists fund the arts?’ Their answers suggest that the reasons for support resist narrow classification: the arts are neither just a minority interest for those with money to spare, on the one hand, nor simply a means to achieve social change, on the other.

Farai Mpfunya of the Culture Fund of Zimbabwe believes that:

‘The arts offer a unique way of appreciating the creative potential of the human mind, the innovative capacity of ideas, products and services, immensely benefiting humanity, often in immeasurable ways.’

Most of those we spoke to had something similar to say, yet art and culture remains a difficult ‘sell’ to many funders.

India Foundation for the Arts supported Mayabazar, a film on Surabhi, a 120-year-old travelling theatre company from Andhra Pradesh.

Why don’t more funders support the arts?

It’s difficult to measure the impact …

Some of the reasons will be fairly familiar – note the word ‘immeasurable’ in Mpfunya’s remark. It raises the perennial question of tangible returns. If it’s difficult to assess the effects of an initiative where there is at least an expected causal link between a project and its outcomes, it’s even more so with an arts project which works on the imagination and emotions of its purveyors and consumers and whose effects are unpredictable – unless one of the outcomes is simply more people participating in the arts and/or enjoying them as spectators.

For some of our funder respondents, access and involvement per se is a major part of the reason for what they do. One such is Kathleen Cravero of the Oak Foundation. Another is Jackie Netto of Neelan Tiruchelvam Trust in Sri Lanka:

‘The show stoppers have been the projects that take art to audiences that would otherwise never be exposed to it.’

However, Ruwanthie de Chickera of Stages Theatre Group, also in Sri Lanka, sees the question of visible returns as an obstacle for some funders:

‘It is easier for people to feel the “results” of their generosity when they deal with material things. Support education and give children school books, support health care and build a hospital ward, help eradicate poverty and build someone a house… these are all things that stand the test of time, which continue to be monuments to one’s generosity.’

Rania Elias of Palestine’s Yabous Cultural Centre, on the other hand, argues that there can be tangible impact:

‘Philanthropic money directed to the arts can influence economic and neighbourhood growth and maturity. Some in the private sector have already come to this conclusion and collected great return on that investment. Arts revive communities and reinforce the economy, create an active and vibrant society, and enhance safety.’

There are more urgent things to support …

Then there is the idea that art is secondary to the more urgent concerns of our time and there are better uses for funding. Leonard Vary of Australia’s Myer Foundation notes – and repudiates – this view. Ruwanthie de Chickera remarks that the arts are ‘very low on the list of worthy causes to put money into’ mainly because funders see more urgent uses for philanthropic money, what she terms ‘the colossal and critical issues of human survival. Poverty, education, basic health care …’

But Evelyn Iochpe of the Iochpe Foundation in Brazil believes that:

‘It is worthwhile to commit to the arts even in a world where we still struggle with hunger, because in such a brutal world as we are living in we need the space for thought, for reflection, for criticism.’

And, as we’ll discuss below, many of our respondents agree with her.

Funding the arts is like building one’s own pyramid …

Ruwanthia de Chickera also hints at a self-serving element in philanthropy which some see as particularly prevalent in funding for art and culture. ‘Building an art foundation seems to mean building one’s own pyramid,’ says Evelyn Iochpe, who dubs this sort of activity ‘artketing’, while Rania Elias notes that ‘some might see it as investment in prestige – especially if the result is their name being engraved on a new wing in a museum or a concert hall.’

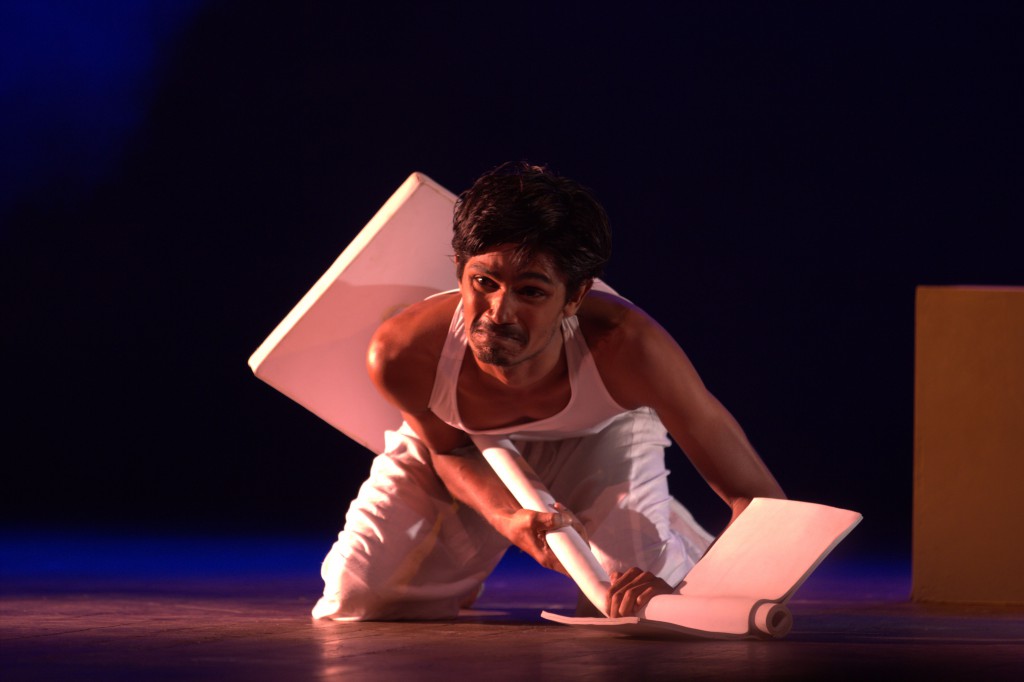

Walking Path, a play without words, produced by Sri Lanka’s Stages Theatre Group and written by Ruwanthie de Chickera. The play examines the widespread urban beautification drive in Colombo.

Arts funding is elitist …

There is also an abiding idea that arts funding is elitist, that it goes to the promotion of so-called ‘high’ art and culture – classical music, opera, ballet – enabling the privileged to enjoy their privileges. Undoubtedly, some of it does, but it doesn’t have to. Even if you don’t subscribe to the dictum that ‘art is anything’, it should be fairly clear that it covers much more than Swan Lake, the Mona Lisa and Ibsen’s plays.

Consider Lia Rodrigues’ description of the founding of the Centro de Artes da Maré in the Maré slums of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the first cultural centre in the area. The Maré is an area of around 132,000 inhabitants, effectively controlled by three different drug-dealing factions. In common with many of Rio’s slums, the area is rarely found on maps of the city, and is practically unknown to most Rio dwellers, as a result of a deliberate tactic by the city which consigns areas like this to silence, neglect and violence. ‘We built this space in Maré not just for the company but for the whole community. It is a common asset.’ She adds:

‘To be based in Maré is certainly a political decision. It means going against this trend of exclusion, invisibility and empty spaces.’

Why philanthropists should fund the arts

For many arts organizations the world over, funds are in short supply, and this is one reason in itself. ‘In Brazil,’ says Rodrigues, ‘there is no real funding programme for culture.’

The same is true in Sri Lanka, says Jackie Netto of Neelan Tiruchelvam Trust: ‘Whether it is art for art’s sake, or art for social change, Sri Lankan artists have limited access to resources. Nor are there established structures or organizations that support them.’

When governments and development agencies support the arts, it is often in the service of economic interests, suggests South Africa playwright Mike van Graan.

‘Freedom of creative expression is often made subject to political and economic interests. It is against this backdrop that philanthropy in support of the arts and artists is necessary to promote and defend independent artistic expression and distribution.’

Promoting discussion of sensitive issues in conservative societies

Funders tend to shy away from the sensitive, the controversial and the political. Neelan Tiruchelvam Trust takes the opposite course, says Jackie Netto, because:

‘We believe that arts (and culture) can be the vehicle for change … when other forms of expression are suppressed.’

It is one of the ways, she believes, that discussion of sensitive issues like gender-based violence (the example she cites) can take place in conservative societies. Since 2001, a quarter of the trust’s funds have gone to support arts projects.

Chris Stone of the Open Society Foundations in the US makes the same point. ‘In closed societies,’ he argues, ‘the connection of artists and their audiences upholds freedom of association and the exchange of ideas in circumstances that otherwise would not be possible.’

For Stone, investment in the arts is a good way of building societies whose difficulties are mediated through discussion, rather than violence:

‘Philanthropic investments in the visual, performing and literary arts are a powerful means of fostering societies where dissent flourishes, scepticism and criticism thrive, and speech – not violence – is the primary instrument of politics.’

You can watch a video about the digital storytelling initiative supported by Neelan Tiruchelvam Trust here:

Changing attitudes

Others emphasize the role that the arts play in changing attitudes. Ruby Lerner of Creative Capital in the US notes:

‘When change happens, one component is always cultural change. You can change legislation, but if people’s hearts and minds don’t change, true progress cannot be made.’

Understanding and shaping our world

Many of our respondents see the arts and artists as playing a role in helping people explain their lives and circumstances to themselves and guiding them in the exploration of solutions. As Omar Al Qattan of the A M Qattan Foundation puts it:

‘A people may be hungry and destitute, or simply troubled and violent, but only when they know why they are so, will they be able to change their condition.’

‘Art can help us reimagine our past and present, and transform our future,’ says Jane Trowell of Platform UK. ‘Supporting the risks associated with contemporary art practice … is the key to expanding the pool of ideas essential for the health, and the survival, of an evolving culture,’ says Mel Chin of Operation Paydirt.

Finding ourselves in a world with increasing inequality, says Arundhati Ghosh of India Foundation for the Arts, with ‘no dearth of wars within and across nations in the name of religion, race, language and ethnicity’, growing intolerance of differences, and freedom of expression continuously at stake,

‘The arts enable us to explore ways of thinking for ourselves, connecting us together through shared experiences – to question, resist, build. Through the arts an individual’s struggle finds voices as many create common spaces to imagine a collective future. The arts make us human.’

‘Social urgency is the most crucial reason why the arts must be supported,’ she sums up.

Shawn van Sluys of Musagetes in Canada takes his starting point in the root of the word philanthropy as meaning love of humanity. ‘That’s a pretty basic criterion for the work of supporting people, projects and organizations in sectors that are in the business of improving life for all people,’ he argues. It also provides the most compelling argument for philanthropic funding for the arts:

‘As a form of inquiry into our ordinary lives and the world around us, the arts lead us to see ever greater possibilities for ourselves and our relationships with each other and our environments.’

Quite simply, believes Marion Potts of Malthouse Theatre in Australia:

‘In funding art, philanthropy funds our ongoing ability to define and shape our world.’

The relationship between the arts and social change

It would be wrong to conclude that funders – much less the artists themselves – see the arts as simply a means to a social end. The relationship between the arts and social change is a much less straightforward one. ‘Everything we are doing is part of an artistic creation, as well as a political stance in the world,’ says Lia Rodrigues. Even funders whose principal purpose is social change seldom see the arts as simply a form of social engineering.

Shawn van Sluys cautions us against assessing the impact of the arts in quantitative ways just to satisfy change agendas:

‘We must eschew the reduction of the arts to mere instruments of social change, measured through the calculus of an over-emphasis on rational thinking. Since philanthropists love humanity, they must play the long game and support artists and organizations for their capacity to help us think deeply, critically and beautifully.’

The Switzerland-based Oak Foundation has no ‘complex theories of change linking art to social justice’, says Kathleen Cravero, but its trustees do believe that there is a connection, and feel strongly that ‘everyone should have access to arts and culture’:

‘We don’t know if these grants will change the world. We do know that they bring joy and beauty into the lives of children and families for whom both are in short supply. And that’s enough for us.’

She instances their support to New York’s Lincoln Center to create new public spaces and wider access to their live events; to Fondation Resonnance in Switzerland, which offers classical piano concerts in hospitals and old age homes; to the Courtauld Institute and the Prince’s Foundation for the Arts in the UK, which connect young people in low-income neighbourhoods to the creative arts and art history.

While Cravero uses the words ‘beauty’ and ‘joy’, others speak the language of rights. Mike van Graan, for example, talks of the ‘fundamental human right of individuals to have access to the arts and to participate in the cultural life of their community’. Most see art as a good in itself, which can produce other goods.

This is why Evelyn Ioschpe sees art education as so important: ‘Through it we can guarantee a school that speaks deeply to the child and involves all her senses. We need brains but we need even more sensibilities to make this and our future world a livable place.’

Part of that wider universe …

None of our respondents see art and culture as something distinct from the rest of life, a diversion from the dour business of living; rather, it is an inseparable part of it. Omar Al Qattan makes this point eloquently:

‘Art is part of culture and culture is that wider universe containing what we see and hear, smell and eat, renege and accept, analyse and consume, and hate and delight in every day.’

All and any experience is mediated through art and can be translated into art, and art can illuminate any experience. This is surely at the root of Ruby Lerner’s remark that,

‘No matter what philanthropists or foundations seek to support, they can find their missions manifested in cultural form, whether it be a documentary film or an art installation.’

You can watch a video about Culture Fund of Zimbabwe’s Children Performing Arts Workshops (CHIPAWO ) programme here:

Why philanthropy must fund the arts

Not only should philanthropy support the arts without blushing; it must do so, in the view of some of our respondents. In societies where artists are critical of the state of things, there may be no alternative source of funding. In addition, suggests Omar al Qattan, ‘there are many societies where the very principle of sharing our wealth, even for something as essential to survival as health or education, is still not accepted’, and this is even more true of cultural life. Until and unless this changes, ‘only philanthropy, or revolution, whichever comes first, will be able to fill the gap’.

Leonard Vary is equally emphatic that philanthropic support for the arts is imperative, not just desirable. More money is being given away than ever before, he observes, and more is going to find cures for diseases or to alleviate poverty and want, and yet these things persist. Why? Because money alone ‘can’t help us navigate our anthropological adolescence’.

‘We need more than money. We need new ideas. We need creativity. We need compassion. And understanding. We need language and we need empathy. Money won’t teach us these things, but art and artists will.’

We can’t dig art up or find it, we have to make it. ‘So we have to fund it. We don’t have a choice. If we’re to survive, we have to support the arts and artists.’

Spanish artist Fernando García-Dory also uses the language of need:

‘The age of Anthropocene needs to define a new paradigm in order for human species to survive. This involves a total reconsideration of art and artists´ role beyond contemporary arts establishment and the limited market and recognition system.’

Can philanthropy be a partner in transformation?

For Mel Chin of Operation Paydirt, the real question is not should philanthropy support the arts, but ‘can it also become a partner in transformation’

‘by being a critical partner, providing means for connections, collaborations, and expertise with the artist to build the capacity to respond to the “storm clouds” of our century.’

The view that funders can be allies is also held by Fernando García-Dory, who sees alliance with like-minded, resourced supporters as crucial to his ‘total reconsideration’ of art and artists: ‘We need those who have an influential position or that have successfully operated in the current economic model, to share in this crucial quest.’

Jane Trowell of Platform expands on the theme – Platform is a group of artists, researchers and campaigners working on social and environmental justice issues.

‘For us it is important that the philanthropists we work with share this commitment and work with us towards joint ends. The most fruitful funder relationships flourish when ideas and creativity flow in both directions.’

There is another side to this coin, however, as she warns. ‘Philanthropy is a fertile part of supporting arts and social change, but not at all costs,’ she warns. Support from the wrong source can be inhibiting as well as damaging to reputation: ‘Tate has been under sustained fire since the Deepwater Horizon disaster for taking money from BP; National Gallery and Science Museum promote Shell through sponsorship. This kind of corporate arts funding prevents transformation instead of enabling it.’ What is important is that there is ‘shared vision, ethics and values’.

With the Culture Fund of Zimbabwe, ‘born out of the collective vision of sector actors to build Africa-driven approaches to nurturing and catalysing creative ideas into activities, events, projects and programmes’, the organization belongs to the sector, says Farai Mpfunya.

Art for all our sakes

In funding the arts, philanthropists need not be afraid that they are fiddling while Rome burns, that they are exalting the inessential at the expense of the indispensable. As our respondents point out in their various ways, artists have been and will continue to be critical in interpreting the world for us, denouncing its defects and proposing alternatives for us to explore. In the words of Marion Potts, ‘art allows us to experience possibility’.

Through the beauty and exhilaration they offer, the arts can lift us out of a condition that might otherwise be scarcely tolerable. Not a bad return on anyone’s investment. If this is impossible to prove, it’s almost equally hard to doubt.

‘I can’t get away from the constant anguish of asking myself if my work is worth it,’ says Lia Rodrigues. It’s something that many funders would probably also ponder, but the constant self-questioning is what keeps artists at the forefront of imaginative and intellectual exploration. In the end, as Ruwanthie de Chickera remarks:

‘It’s an act of faith, for sure, but there is nothing more inspiring to an artist than someone’s faith in the value of their work. It is what keeps us going.’

Alliance would like to thank the following for contributing to this article:

The funders

Kathleen Cravero Oak Foundation, Switzerland

Arundhati Ghosh India Foundation for the Arts

Evelyn Iochpe Iochpe Foundation, Brazil

Ruby Lerner Creative Capital, US

Farai Mpfunya Culture Fund of Zimbabwe

Jackie Netto Neelan Tiruchelvam Trust, Sri Lanka

Omar Al Qattan A M Qattan Foundation, UK and Arab region

Shawn van Sluys Musagetes, Canada

Chris Stone Open Society Foundations, US

Leonard Vary Myer Foundation, Australia

Artists and arts organizations

Ruwanthie de Chickera Stages Theatre Group, Sri Lanka

Mel Chin Operation Paydirt, US

Rania Elias Yabous Cultural Centre, Palestine

Fernando García-Dory Spain

Mike van Graan South Africa

Marion Potts Malthouse Theatre, Australia

Lia Rodrigues Redes da Maré, Brazil

Jane Trowell Platform, UK

Andrew Milner is Alliance associate editor. Email am@andrewmilner.free-online.co.uk

Caroline Hartnell is editor of Alliance. Email caroline@alliancemagazine.org

Comments (0)