As the articles in this Alliance special feature make clear, philanthropy advice is a small field relative to the growing number of donors and potential donors, but it’s a growing one. Among those increasingly offering philanthropy advice are the private banks. For all those who believe in the growth of philanthropy, this has to be ‘a good thing’. But is it?

This is a completely unregulated field. By their very nature, banks are in a position to abuse the trust placed in them by their clients. There can be bad practice, as illustrated by the following story, told to us by Timo Reinfrank of Amadeu Antonio Stiftung.

A female donor got to know Amadeu Antonio Stiftung, a German foundation committed to strengthening democratic civil society and protecting minority rights, and felt it was the perfect fit for her giving interests. She told her bank about it, but the bank advised her not to invest in the foundation but to set up her own entity, managed by the bank. In the end, she followed her bank’s advice. The bank now hosts a foundation with exactly the same mission as Amadeu Antonio Stiftung but without the experienced staff. The donor is not surprisingly rather disappointed.

It is not hard to understand the bank’s interest in this: to keep their client’s assets within the bank. This is a perfectly legitimate – and natural – thing for a bank to want. Banks are businesses and their business is managing assets. But in this case the bank’s natural interest in retaining as much of its client’s assets as possible was in conflict with its client’s philanthropic interests. If banks offering philanthropy advice are to avoid such conflicts of interest, they will need to be very clear about what they are doing and why.

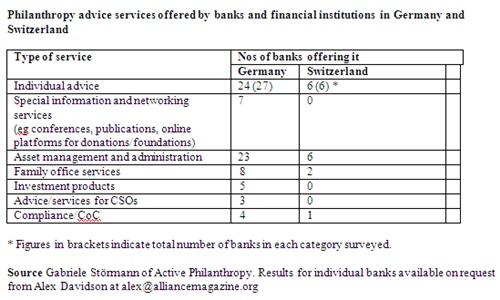

The table below presents the results of a survey of banks in Germany and Switzerland, which demonstrates clearly how widespread the offering of philanthropy services by banks now is – and therefore how widespread the potential for bad practice.

Managing philanthropic assets

I talked to a number of heads of philanthropy at different private banks in connection with this issue of Alliance. (Mario Marconi, Mark Evans, Philippe Depoorter, Nathalie Sauvanet) In addition to the value to the bank’s clients, emphasized by all those I spoke to, it is clear that keeping clients’ assets within the bank is an important reason for offering philanthropy services. Another could be termed simply ‘keeping clients’. This is summed up succinctly by Philippe Depoorter of Banque de Luxembourg. ‘There are two reasons why we offer these services,’ he says. ‘First, because it increases the trust of our clients and strengthens our relations with them. … If we can help them to carry out their philanthropic projects, they’re grateful to us, and more likely to stay with us for the rest of their banking business, which is our main purpose. The second reason relates to asset management. When appropriate, we manage the philanthropic assets.’ He makes no apologies for this: ‘Here we add value for our clients because managing assets is what we do best.’

A similar range of motivations is cited by Mark Evans of Coutts, who also mentions the importance of attracting new business ‘because we can offer something that a lot of other private banks still don’t and we are perceived as a market leader’. What is notable about Evans’ five-point list of reasons is that they all relate clearly to the business. ‘Since we work for a bank we have got to be very precise about the way in which we add value to the bank as well as to the client,’ he says. This is not to suggest that the people who head up philanthropy services at banks are not committed to philanthropy. The ones that I spoke to clearly are. Nathalie Sauvanet of BNP Paribas comes from an NGO rather than a banking background.

Advising clients about charities

The other element in the case cited above is advising the client about particular charities. Depoorter, Evans and Mario Marconi of UBS all say that selecting projects and recommending particular NGOs is something they stay clear of. ‘Our clients’ needs are so diverse that we could never have proper expertise in all the topics that clients are interested in,’ says Marconi. ‘We don’t recommend individual charities,’ says Evans. Depoorter is characteristically emphatic that this is beyond the bank’s competence: ‘As a bank, we do not have experience of these activities and as such are not in a position to add value … If we recommended the wrong NGO, we’d be responsible.’

BNP Paribas is the exception here in that it does advise clients about particular NGOs. But, Sauvanet insists, they have ‘no worries’ because they have ‘a very rigorous due diligence process, taking six to eight months. Second, we never recommend one charity. We begin with a pool of 100, then reduce to 20. Then we work with the client to reduce this to five.’

In addition, both UBS and BNP Paribas have their own foundations, the UBS Optimus Foundation and Fondation de l’Orangerie, respectively. Each offers a small selection of carefully vetted projects that their clients can invest in. Both Marconi and Sauvanet see this as something likely to appeal to new donors, whereas more established ‘top end’ donors are more likely to want what Sauvanet calls ‘tailormade’ solutions.

Sauvanet is clearly aware of the potential issues when a bank suggests that its own clients should invest in a foundation whose assets they manage. Fondation de l’Orangerie is established both in Switzerland, as a fully independent entity, and as a sheltered foundation within Fondation de France. ‘Fondation de France offer two possibilities for sheltered foundations: the assets can stay with them or with the donor,’ she explains. ‘For the sake of good governance, we chose the former for the French foundation.’ She also stresses that they have field experts on the board who ‘have the right to veto projects’.

A case for regulation?

It is a well-recognized anomaly that bankers offering investment advice often work in a tightly regulated environment while those same bankers offering philanthropy advice are completely free of regulation, although the sums involved can be just as large.

Melissa Berman argues for a code of ethics for philanthropy advisers. This is not to suggest that ‘the field of philanthropic advising is rife with bad advice and hidden self-interest’, she says. For her, ‘professional standards, including a code of ethics, are important mostly because they begin a dialogue between the donor and the adviser that emphasizes that this work is being done professionally and thoughtfully’. But this doesn’t mean there is no bad advice or hidden self-interest.

In fact, the first step seems to be to make sure that the self-interest is no longer hidden. This is a point strongly made by Felicitas von Peter. ‘What is crucial,’ she says, ‘is that individuals and institutions giving advice are completely open and transparent about why they are doing it. Otherwise, the client doesn’t know what he or she is buying … I would argue that the biggest flaw in our sector is the lack of transparency towards our clients about what drives each of us.’

For the moment, in a profession that doesn’t have a recognized code of ethics let alone external regulation, it is up to those offering philanthropy services to make sure they are acting correctly, and transparency seems to be the first step. Alliance will be holding a breakfast meeting in September on the topic ‘Should philanthropy advice be a regulated field?’ We will report back to our readers.

Comments (0)