In a project to which multi-stakeholder dialogue is central, choosing the right stakeholders is paramount. This article describes how social network analysis transformed the mirage of a multi-stakeholder dialogue about groundwater in Jordan into reality.

Water in Jordan is a valuable and scarce resource. Groundwater provides 50 per cent of the country’s total supply, but it is becoming short in quantity and quality. In 2009, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Water Programme partnered with Jordan’s Ministry of Water and Irrigation to set up the Highland Water Forum. This council of water users and other stakeholders aims to reach consensus on the use of Al-Azraq, one of the most overpumped groundwater aquifers in Jordan. This will help the ministry to develop an integrated action plan to reduce groundwater extraction to a sustainable level.

Al-Azraq is the largest of the Jordanian aquifers (12,700 km2). A little less than half of the water that is extracted goes to the major cities of Amman and Zarqa and the remaining extraction is done in situ by farmers. Laws and regulations governing this do exist, but farmers have resisted their implementation. The challenge was therefore not technical; rather it lay in the social structure of the country. Though a modern, peaceful state in the Middle East, Jordan is nevertheless governed by tribal considerations. Its society is based on loyalty to family, clan and tribe.

While it was clear that representatives of the landowners and well-owners and farmers had to be part of the forum, the Jordanian agricultural community is largely unorganized. The only way to establish a dialogue was to ‘hand-pick’ the farmers’ representatives. The task seemed impossible: not only is the basin one of the biggest in Jordan but it has hundreds of registered well-owners. How could one choose no more than 20 farmers without disrupting the social balance of the area?

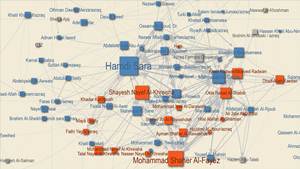

Social network analysis promised an effective strategy. FAS, the research consultants commissioned, designed a questionnaire and randomly selected an initial 20 farmers from the Ministry of Agriculture’s database of more than 1,300. Every interview yielded socioeconomic data, knowledge of the extent of awareness of the groundwater problems, and nominations of representatives to the forum. The nominated farmers were then sought out and interviewed, which produced further nominees. This dynamic and open process whereby one interviewee led to others was called the ‘snowball’ method.

Social network analysis promised an effective strategy. FAS, the research consultants commissioned, designed a questionnaire and randomly selected an initial 20 farmers from the Ministry of Agriculture’s database of more than 1,300. Every interview yielded socioeconomic data, knowledge of the extent of awareness of the groundwater problems, and nominations of representatives to the forum. The nominated farmers were then sought out and interviewed, which produced further nominees. This dynamic and open process whereby one interviewee led to others was called the ‘snowball’ method.

All told, more than 200 interviews took place over a period of two months. The data was sent to the consultants weekly to undergo social network analysis, which made it possible to identify the stakeholders and to analyse the relationships that bind them. The number of nominations or votes that one farmer received was an indicator of the trust that others placed in that farmer, and the 20 interviewees with the highest number of ‘votes’ were asked to represent farmers at the forum. This extensive selection process also served to introduce the Highland Water Forum to more than 200 farmers all over the basin. In effect, it marked the beginning of the dialogue.

All told, more than 200 interviews took place over a period of two months. The data was sent to the consultants weekly to undergo social network analysis, which made it possible to identify the stakeholders and to analyse the relationships that bind them. The number of nominations or votes that one farmer received was an indicator of the trust that others placed in that farmer, and the 20 interviewees with the highest number of ‘votes’ were asked to represent farmers at the forum. This extensive selection process also served to introduce the Highland Water Forum to more than 200 farmers all over the basin. In effect, it marked the beginning of the dialogue.

Many of those selected were both the richest and the most influential among the farmers, but the process was especially important to the less well-connected. It provided a sanctioned and transparent method for them to participate in the decision-making process and to have their views included. In a society that is strongly interrelated, with such a controversial process (dialogue) and an especially unpopular topic (groundwater rights), the choice of representatives was the one thing that was not contested.

Over the three years since the Highland Water Forum was set up, the farmers and the water-governing authorities have continued to contribute their time and effort. The forum has met nine times. During this time, it has produced a paper making recommendations about laws and regulations to govern groundwater use. It is currently working to produce the first draft of an action plan for sustainable management of the Al-Azraq groundwater basin, which it was mandated to develop by the Cabinet of Ministers in 2010. Only recently, the GIZ Water Programme was approached by the Water Authority of Jordan to carry out a similar exercise in Yarmouk River Basin, an important source of surface and groundwater in the north of Jordan. This time, the financing will come from the European Union Delegation in Jordan. Once again, social network analysis will play a key role in forming the Yarmouk River Council.

Nour Habjoka is Technical Adviser at the GIZ Water Programme. Email nour.habjoka@giz.de

Comments (0)