Networks have been the buzzword of the last decade. But what do networks really mean for philanthropic work and what can philanthropists do for networks? Where does their promise lie? What sort of investment is required to utilize the ‘power of networks’?

The problems confronting us are getting graver by the day and the opportunity costs of where we put our money are increasing.

Network scientists in the fields of sociology, computer science, physics, biology and ecology have gained deep insights into the nature of networks in the last 20 years. In this special feature, some of the most illustrious representatives from the worlds of science, management and philanthropy share their insights. The guest editors themselves combine these different worlds.

What are networks and what do they do?

So what are networks? Simply put, everything that is made up of relationships can be called a network. People work together or not, exchange information or not, are friends, enemies or indifferent to each other, trust each other or not – all those relations form what can be described as a network. There are an infinite number of such positive, negative or neutral transactions and relationships in both the human and the non-human world.

Why should philanthropists care about this complex web of interaction? First, networks are probably the most important factor in human economic survival and happiness. Human beings are literally not capable of living without social networks and we as philanthropists should care about those who are deprived of the social capital they provide. But there is a more functional reason why we should be interested in understanding networks: in order to reach our philanthropic goals, we invest resources, but those resources depend for their effectiveness on a network of people setting the right goals, defining the right tasks, identifying and responding to opportunities, working together even in difficult environments. How many projects fail because people do not cooperate due to status rivalry, a do-it-alone mentality or mistrust? How many projects get stuck because of lack of openness and innovation? How many resources are wasted because projects never reach critical mass?

A recent article in the New Yorker describes the trend towards networked teams. Analysis of almost 20 million peer-reviewed academic papers and 2.1 million patents from the past 50 years has shown that levels of teamwork have increased in over 95 per cent of scientific subfields. ‘The most frequently cited studies in a field used to be the product of a lone genius, like Einstein or Darwin. Today, regardless of whether researchers are studying particle physics or human genetics, science papers by multiple authors receive more than twice as many citations as those by individuals.’[1]

When we talk about networks we are literally talking about the social infrastructure of philanthropic success. It’s not a matter of choice: you can’t not have a network, just as you can’t not communicate. Even if you don’t like somebody, it creates a negative bond – just think about the relational charge behind resentment, envy or competition. We can either manage that network or not, but it will have its impact on performance and outcome. You can pour as much money as you want into a network: if it works badly, your money will evaporate without any sustainable impact.

We are not talking about networking technology or social media here (Facebook, Twitter, Wikis, etc) – though technology can help to support networks by reducing transaction costs. We are talking about the wide variety of relationships and interactions between individuals and organizations. Now think of the difficulties we work under. Investors expect more in less time; resources are scarce; we are all exposed to constraints, stress and sometimes drama. One of the key questions in this special feature therefore is: how can we support the emergence of robust, adaptive and stress-resistant networks which are capable of delivering sustainable philanthropic value and staying open to new opportunities even in a rapidly changing environment?

The variables of success

In the last two decades network science has contributed substantially to our understanding of the drivers of such resistant and adaptive networks. At the risk of simplification, let’s break the findings down into two success variables: first, the amount of opportunity for individuals and partners to co-create value. Difference and variety breed opportunity. The greater the resources going through the network, the more likely it is that a diverse network will establish itself through self-organization, so diversity is at the same time a cause and a symptom of richness of resources that ‘feed’ the network with energy. On the other hand, the greater the amount of shared identity, of values and goals that partners have in common, the stronger the network will be. Shared purpose and shared stories not only create identity, they also develop trust, one of the most important means to reduce transaction costs in a network. So there is a correlation between the transactional and relational component in a network, the common denominator being the amount of trust between network partners.

A typology

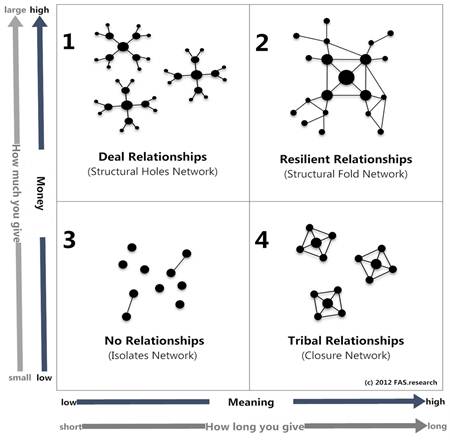

Simply put: when we talk about effective and efficient networks, it’s all about money and meaning. A network in which people don’t share any common story and where there are no resources will not last for long – it’s like a casual affair or a random encounter (network type 3 ).

Types of relationships and networks

Let’s think about another constellation of the two parameters money (resources) and meaning (shared identity and goals): in network type 1, you have a lot of resources and opportunity but no shared values and goals. Networks like this are dominated by utilitarian deal relationships between ‘strangers’ coming from different worlds, usually organized around a single focal actor distributing or managing the resources (eg the main contractor or main donor in projects). After the money is spent or the deal is done, the relationship dissolves.

Whether this is good or bad depends on the goal. If you want to solve a problem quickly and bring in experts for certain tasks, structural hole networks will do well. They span bridges to other worlds and expose network members to new ideas and opportunities. Generally, the risk of deal-based networks is that the bridges are weak and people put their own interests first. Philanthropy seems to be moving more and more in the direction of this kind of short-term deal relationship and value is getting more important than values. From a network perspective, this means that the strength of such links is decreasing and the risk of fragmentation after the gold rush is over increasing.

Let’s look at network type 4. Here people share a lot of common purpose but lack opportunity and resources. Does this sound familiar? For many non-profit communities this is daily reality. Since resources are limited, there is a natural tendency to create boundaries around the community to avoid competition. What you get are tribal-like small world networks with few, if any, connections between them – as is often the case with isolated social movements. The tendency of some more established non-profit communities to shun collaboration with other non-profits is a simple response to the lack of resources. Intense competition for donor money moves networks either to type 3 (competition between individuals) or, where there is considerable shared meaning, to type 4 (competition between tribal communities, social movements or organizations).

Capitalizing on unexpected opportunities

This typology shows clearly what enormous impact philanthropic investments can have on the structure of networks and the relationships within and between them. Steady inflow of resources can transform a tribal network (type 4) into a resilient network with deep relationships and flexible cross-boundary collaboration (type 2). This is the ideal type of network if you want to establish a sustainable, self-reliant network with the capacity to create value and take advantage of unexpected opportunities. Many social movement activists and scholars believe that anticipating and responding effectively to unexpected political opportunities is the key factor in creating social change. Philanthropy can help social movements leverage these unexpected opportunities by building trusting relationships within loose networks in advance.

The Arab Spring is full of examples of existing high-trust organizations that were able to leverage very small amounts of resources to achieve huge political and social changes once they formed a loose network – from the non-violence trainers with the Academy of Change to the highly disciplined Muslim Brotherhood. Once these diverse independent organizations found their common meaning they could consolidate resources into a loose network with powerful results.

No successful network without money and meaning

Money obviously matters. Experience has clearly shown that you can’t moralize starving organizations into collaboration. If investors want to foster more collaboration between small organizations to leverage resources, they are more likely to succeed if they commit themselves to mid- to long-term investment and avoid short-term utilitarian mergers. But giving more money works only if grantees can move to a new common narrative and identity. It’s hard to give up one’s own old tribal story, but working in a larger network requires members to feel part of a new common identity.

To know that there is a common road ahead of us completely changes the perception of costs and returns. In a deal-based network partners want immediate returns. But building trust takes time. Networks without common meaning will decay in times of stress due to lack of bonding. Resilient networks stick together in times of crisis because the shared values mean partners help each other out through their access to different resources and solutions. The best investment in an uncertain future is in a portfolio of diverse long-term relationships. Without shared meaning, no network can resist stress in the long run. Deal-based networks give you only a short-term solution.

A portfolio approach

Should philanthropic investments move from short-term to long-term engagement? It depends on what you want to achieve. To fix problems quickly, structural hole networks are the way to go. If you want to raise awareness and spread the word, the same. Bridging fast to spread the idea is more important than the slower process of bonding. But if you want to be really transformative, there is no alternative to mid- to long-term engagements. A portfolio approach allows you to make short-term, small grants to trigger and initiate network formation for specific tasks, and long-term, large grants to foster resilient, adaptive networks with a strong identity that also bridge worlds.

Philanthropy can make a huge difference in creating and shaping networks, which need both money and meaning. And both these elements need to be managed.

Managing money and meaning

How can the transactional (money) and relational (meaning) capital be managed in a network? Every relationship in a network has its own cycle, similar to our own intimate relationships: you meet someone, you fall in love, there is a honeymoon, then routines kick in; in order to keep the relationship alive you have to renew or sometimes even reinvent it. The same holds true for each link in a network and for the whole network.

How can the transactional (money) and relational (meaning) capital be managed in a network? Every relationship in a network has its own cycle, similar to our own intimate relationships: you meet someone, you fall in love, there is a honeymoon, then routines kick in; in order to keep the relationship alive you have to renew or sometimes even reinvent it. The same holds true for each link in a network and for the whole network.

How can the network keep up and renew its capability to produce value and be valuable for the network members? Network science in the field of systems ecology has shown that the secret of healthy networks capable of growing and developing over a long period is what might be called ‘stable instability’. You need a group of people different enough to sometimes surprise or even disturb each other but who have enough in common and share a common goal.

In successful start-up companies, you typically have the charismatic founder/entrepreneur who starts the project but gets bored quickly. Then you need a manager to establish structure and scale processes, but they tend to become bureaucratic. You need the seductive salesperson who closes the deals but tends to sell products that are not yet developed and is hated by the engineers for that. You need the out-of-the-box thinker who comes up with new solutions all the time but constantly wants to change everything, which drives people around him crazy. Above all you need the investors, mentors and board members who provide start-up capital and good advice. So there are different roles and different tensions, but if the purpose is big enough and the conflicting forces are focused on the goal, you have a powerful, resilient network.

Meaning and money first, technology second

Managing ambiguity and imbalance is therefore the main challenge for a network. Diversity always means friction, and friction creates heat. Where there is no heat, there is no work and no impact. And of course all the modern social technologies like Wikis, Twitter and Facebook, which help to manage the imbalance in the network by making things visible and more easily accessible (visibility always fosters trust!), should be applied wherever and whenever possible!

But social media are not a panacea. They are in many respects very useful, but no technology in the world can fix a wrong mix of personalities or roles, a lack of resources or a lack of shared vision and intention. As Malcolm Gladwell points out in his renowned New Yorker article ‘Small Change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted’, strong ties between individuals are central to the success of the high-risk activism that leads to fundamental social change. Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam documented this ‘strong-tie phenomenon’ in Freedom Summer, his study of the high-risk, high-commitment activism that many believe led to the eventual success of the US civil rights movement in the 1960s.

You don’t start building a network by setting up a technology-based platform. Technology helps to reduce transaction costs and synchronize behaviour and thus saves resources, but it can’t substitute for a lack of values and value. The most sustainable and effective way to reduce economic transaction costs is to establish trust; technology will always play an important supportive role but it can’t be a primary driver in this regard. According to Gladwell, ‘Facebook and the like are tools for building networks, which are the opposite, in structure and character, of hierarchies. Unlike hierarchies, with their rules and procedures, networks aren’t controlled by a single central authority. Decisions are made through consensus, and the ties that bind people to the group are loose.’

Hierarchies and networks

Gladwell goes on to say that ‘the drawbacks of networks scarcely matter if the network isn’t interested in systemic change – if it just wants to frighten or humiliate or make a splash – or if it doesn’t need to think strategically. But if you’re taking on a powerful and organized establishment you have to be a hierarchy.’

Understanding the need to link hierarchical organizations to self-organized networks was key to the founding strategy of the Global Greengrants Fund – a pioneer in global small grants philanthropy for environmental and social change. Greengrants was originally structured to blend the opposite strengths of hierarchy for fundraising and networks for grantmaking. For fund aggregation, Greengrants reached up to elite networks of grantmaking foundations such as the Environmental Grantmakers Association and the Consultative Group on Biological Diversity. For grantmaking strategy, it reached down to the grassroots through existing global networks of environmental NGOs such as the Rainforest Action Network, Friends of the Earth and Earth Island Institute. As Greengrants evolved it become a semi-classical philanthropy for fund aggregation in the US, on the one hand, and a radical, trust-based global distribution network for strategic grassroots grants on the other. The emergence of the internet at the same time facilitated both hands by enabling rapid, unambiguous global communication and low transaction costs.

The importance of people

We have talked so far about two success variables – money and meaning – but we would like to add a third, complementary personalities, into our formula for effective networks:

Effective Network = Money + Meaning + Complementary Personalities

In practice, this means that a philanthropic investor should come on the scene as soon as possible to see if there is enough diversity and bandwidth among the network members, or if they are too similar to each other in what they are good at. We don’t see any real alternative to doing this other than by meeting the people in person or having somebody you trust to do this for you. This holds true if you want to assess the internal network of an organization or an alliance or coalition between different organizations.

Consider, too, the power of story, the meaning. Ideas can be a real energy source that helps a network get through a crisis or bridge a short-term squeeze in resources. And decide, given your goal, how to allocate your investments – long-term or short-term, and how much. In terms of network formation this is a fundamentally strategic moment. By deciding on timeframe and quantity you are not just helping individuals to work for the good; you are influencing what kind of network it will become.

If you need help in this decision-making process, science-based social network mapping can help you to see the health and shape of a network. Social network graphs show you how people are connected; you can see as in an X-ray picture the form/type of a given network and whether the form is aligned with the goal. If it isn’t, you have three levers (money, meaning and people) to move in the right direction to get the best outcome for your philanthropic investment.

The other articles

Based on what our scientific work and practical experiences have taught us over the last years and what we thought our readers would find useful and interesting, we invited a group of leading systems thinkers to share their perspectives on what philanthropy can learn from a wide spectrum of natural sciences, including physics and biology as well as social sciences like sociology and economics.

Geoffrey West, a theoretical physicist at the Santa Fe Institute, outlines his research into the universal scaling principles of networks in nature and how those principles can be transferred to social networks such as cities and corporations, and what that means for philanthropists who want to harness empirical evidence about how complex adaptive systems scale. Renowned conservation biologist Buzz Holling talks about how adaptive cycles in ecology lead to resilience systems and what philanthropists can take from this. We asked ecological network theorist Bob Ulanowicz what philanthropy can learn from coral reefs, which are reasonably stable because there are multiple ways of feeding back. Author of Macrowikinomics Don Tapscott applies a set of five key business principles of ‘networked intelligence’ to philanthropy.

Other contributions include Lori Bartczak of Grantmakers for Effective Organizations and Diana Scearce of the Packard Foundation looking at how we can combine a network mindset with strategic grantmaking; Ezra Mbogori of Akiba Uhaki Foundation on the emergence of the new African Grantmakers Network; and network guru Beth Kanter describing a vision for a future in which chief network officers play a central role. Nour Habjoka of the GIZ Water Programme describes how social network analysis helped with a multi-stakeholder dialogue on water issues in Jordan, while Jennie Curtis of the Garfield Foundation explains how the RE-AMP Network helped to address complex climate and energy challenges in the US upper midwest.

We hope you find this discussion about networks and complex adaptive systems useful in combining money and meaning to influence social change. If not, we’re sure you’ll adapt …

1 Jonah Lehrer, ‘Groupthink: The brainstorming myth’, New Yorker, 30 January 2012. http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2012/01/30/120130fa_fact_lehrer

The guest editors for the Alliance special feature on ‘Networks and philanthropy’ are:

Harald Katzmair Executive director of FAS.research – Understanding Networks, based in Vienna, Austria. Email harald.katzmair@fas.at

Chet Tchozewski Founder of Global Greengrants Fund and a member of the boards of the Council on Foundations and the Environmental Grantmakers Association. Email Tchozewski@gmail.com

Comments (0)