The world is facing a challenge. The number of people forced to leave their home has reached a record high of 60 million. While the spotlight has been on Europe, more than two-thirds of the displaced people are still living in their own country. Of those who have crossed national borders, 86 per cent are hosted by nearby developing countries. In fact, none of the top ten destination countries for refugees is classed as a high-income country; the bulk of Syrian refugees are living in the neighbouring countries of Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. If those countries are to cope, they will need help from the international community with the financial strain migration can place in the short term on a country’s social and economic fabric.

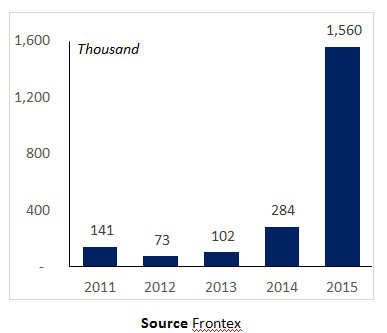

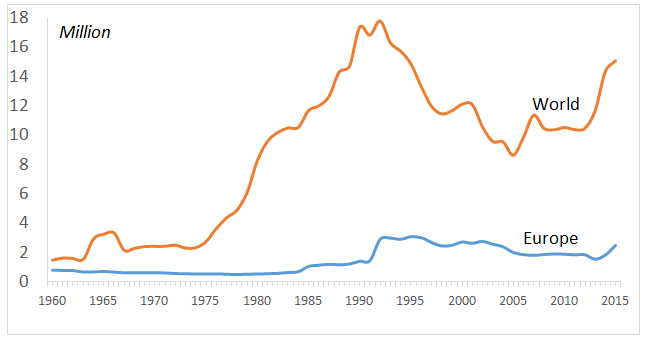

Over 1.5 million people crossed into the EU in 2015, compared to an annual average of 100,000 during 2009-13 (Figure 1). As a result, the stock of refugees and asylum seekers in Europe increased from 1.9 million to 2.5 million during the same period (Figure 2). Germany alone received nearly 1 million asylum applications last year. Most of the migrants are refugees from Syria, although there are refugees and migrants from Afghanistan, Iraq, Eritrea and Pakistan and other countries as well.

Figure 1: The number of migrants and refugees crossing into the EU rose sharply in 2015

However, while Europe’s migration crisis has been highly visible in the media and public discourse, the biggest burden of hosting refugees is being borne by Syria’s neighbouring countries. The number of Syrian registered refugees in Turkey stands at over 2,180,000, while there are 1.1 million in Lebanon, and over 600,000 in Jordan. The refugees in Lebanon represent nearly 25 per cent of the population, and in Jordan, 10 per cent, compared to Germany’s 1.3 per cent.[1] According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 86 per cent of refugees worldwide are hosted by developing countries. The top ten host countries are Turkey, Pakistan, Lebanon, Iran, Ethiopia, Jordan, Kenya, Chad, Uganda and China; none of these is a high-income country.

‘While Europe’s migration crisis has been highly visible in the media and public discourse, the biggest burden of hosting refugees is being borne by Syria’s neighbouring countries.’

Challenges of hosting refugees

Unlike economic migration, which is largely beneficial to the migrants as well as their countries of origin and destination, forced migration entails considerable suffering for migrants. While, as discussed below, refugees can be economic assets for the host countries in the longer term, they often impose a substantial short-term burden, through increased public spending on schools, hospitals and public infrastructure. Higher demand for food and housing pushes up prices, while refugees competing for lower-skilled jobs pushes down wages.

The large number of Syrian refugees in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan has imposed significant fiscal costs on the respective governments to safeguard the human, social and economic capital of the host countries and the displaced communities. The government of Turkey has reportedly spent $8 billion already. This year’s Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan estimates a funding gap of nearly $3 billon for Lebanon and Jordan. Host countries need to arrange short-term and long-term financing, since the refugee situation could go on for several years. Since concessional financing is not available for these middle-income countries, the World Bank Group – in partnership with the UN and the Islamic Development Bank Group and other stakeholders – is seeking to mobilize grants and concessional financing to strengthen the capacity of countries and communities hosting refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) to absorb the shocks to their economic and social fabric.

The burden of hosting refugees is also high for Europe, although Europe has coped with even larger numbers of refugees in the past, notably in the early 1990s. At a practical level, European countries are finding it difficult to agree on a formula for burden sharing based on absorptive capacities of nations, and the lack of agreement has prompted many countries to tighten border controls for movement of people within the EU. While it is generally accepted that individuals should not be forcibly returned to areas where they are in danger of injury or persecution, countries are adopting more restrictive rules for who qualifies as a refugee. This has led to new challenges for managing economic migration, the demand for which is large globally, and arguably even larger in the slowing, and ageing, economies of Europe.

Figure 2: The current stock of refugees and asylum seekers in Europe and worldwide is still short of the historical high reached in the early 1990s

Economic migration vs forced migration: the bigger picture

Economic migration has always been significantly larger than forced migration. Globally there are around 250 million international migrants – persons born in a different country from the country of current residence. Refugees make up less than 8 per cent of that number at just over 15 million (excluding 5.1 million Palestinian refugees).

Migration is an integral component of economic growth. As countries industrialize or transform into service economies, people move to places where the jobs are located. Migration is largely within national borders, but often people cross over to work and live in foreign countries.

Voluntary migration driven by a search for employment is overwhelmingly beneficial to all concerned – the migrants themselves, the countries of origin and the countries of destination. In 2015, worldwide remittance flows are estimated to have exceeded $600 billion. Of that amount, developing countries are estimated to receive over $440 billion, nearly three times the amount of official development assistance. These remittances are used for purchasing food, housing and healthcare for the family, education for children, and business investments. Over time, migrants facilitate exports and imports between countries. They also share their knowledge and expertise with people back home. Some of them return home after years of working abroad, bringing with them skills and savings. In the destination community, migrants provide cheap labour and scarce skills for their employers; over time, many of them invest in real estate, businesses and new enterprises that create employment.

Many of these observations apply to the victims of forced migration, too. In the longer term, refugees can be economic assets if they are integrated into the host communities. They augment labour supply in economies where the work force is shrinking; they bring new, complementary skills; many come with new sources of financing and create new businesses and employment for native workers; they increase demand, providing stimulus for economic growth; and they can expand international trade through their networks.

A global perspective

Refugees make up under 0.3 per cent of the global population. Viewing the current refugee crisis as a global problem would make it more manageable. And in the long term, the root causes of forced displacement must be addressed through development efforts in the countries afflicted by conflict and fragility.

Dilip Ratha is head of the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development and a lead economist in the development economics unit of the World Bank. Email dratha@worldbank.org

Footnotes

- ^ Figures taken from the 3RP Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan 2016-2017

Comments (0)