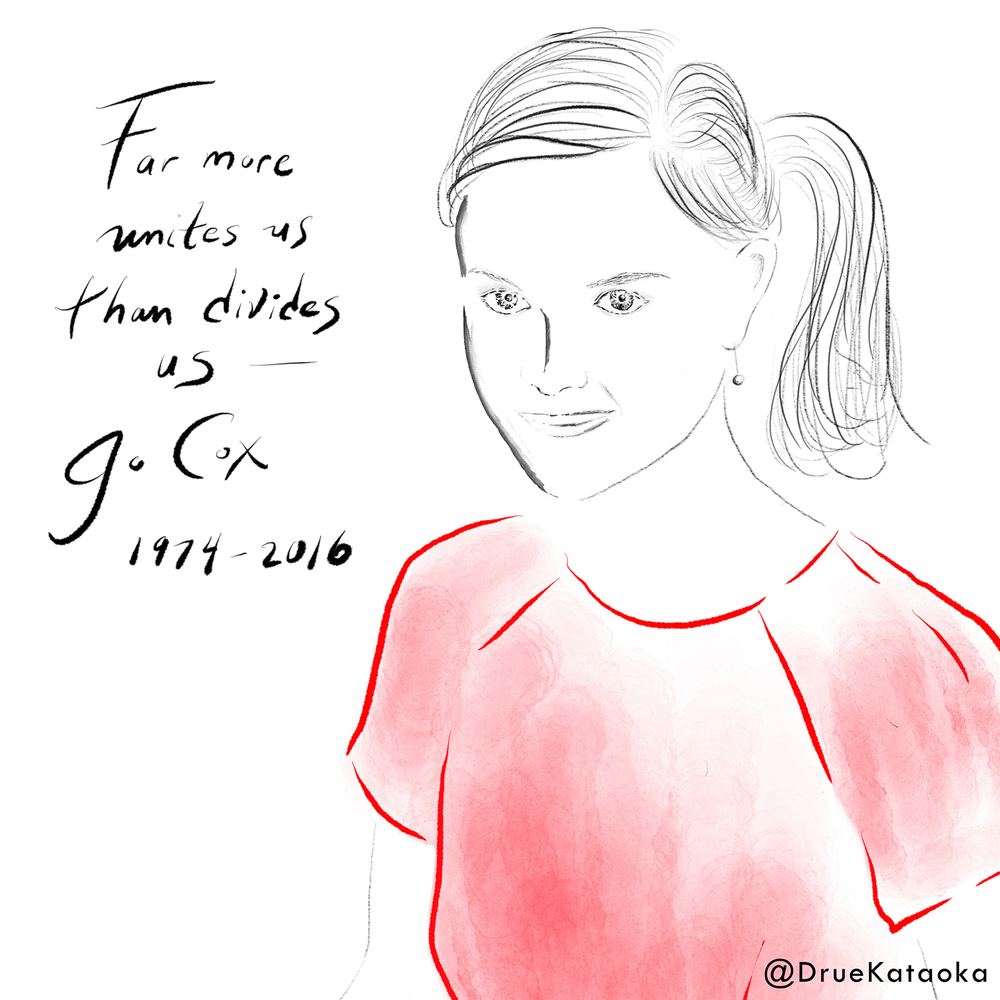

In June last year, just before the Brexit vote, UK Member of Parliament Jo Cox was murdered, becoming the victim of the sort of hate crime she was campaigning against. Her husband Brendan, who himself works on fighting hatred and division, talks to Alliance editor Charles Keidan about the public revulsion and response to her death, setting up the Jo Cox Foundation, the couple’s belief in community, and the need to combat the sense of alienation at the root of unease and tensions across Europe.

In the aftermath of Jo’s death there was a huge public response. Can you tell me what has happened subsequently and how that response has been channelled?

The year before June 2016, I’d been working on combatting the rise of far-right populism and building more inclusive communities. Jo and I had talked about this very regularly.

There is a general view that, since the Second World War, we have been moving in the right direction, with some bumps here and there, but sometime in early 2015 we both started to worry whether that was still true and that there was a threat to community cohesion, to the functioning of our democracies. It changed our priorities.

There is a general view that, since the Second World War, we have been moving in the right direction, with some bumps here and there, but sometime in early 2015 we both started to worry whether that was still true and that there was a threat to community cohesion, to the functioning of our democracies. It changed our priorities.

Both of us had worked almost exclusively internationally – Oxfam, Save the Children, Crisis Action – but just as Jo was standing for parliament in 2015, we started to see the need to focus much more on the threat to communities in Europe and the UK. So the year before Jo was killed, we’d been thinking about rising hate crimes, growing populism, and for it then to come to the centre of our lives was unbelievable and horrific.

When it happened, I knew that I wanted to take forward her causes, and in particular to take on the hatred that killed her, so in the early days, I wanted to provide people with an opportunity to contribute to the causes that Jo cared about.

When it happened, I knew that I wanted to take forward her causes, and in particular to take on the hatred that killed her.

Our friends helped pull together the GoFundMe campaign which tried to reflect the different things that Jo cared about, which are quite disparate at first sight. HopeNotHate works on anti-extremism, the Royal Voluntary Service (RVS) is community-based, and particularly focused on loneliness, which was at the centre of a lot of Jo’s thinking, and the White Helmets, which represents her international work.

Hands in Solidarity: Hands of Freedom mural on the side of the United Electrical Workers trade union building on West Monroe Street at Ashland Avenue in Chicago, Illinois.

The thing that tied together those three strands besides Jo was that sense of solidarity, which connects with your theme.

Whether it’s about bringing communities together, the whole civilian population of Syria, or lonely individuals left to fend for themselves, there is a connection in what we’re trying to build. Solidarity is one word for it.I think Jo would have talked about it more as empathy. At all events, the response was huge and very quickly, we raised extraordinary amounts of money – £1.5 million in a matter of days.

I think that level of public engagement and support came about because people felt powerless and they wanted to do something to send a signal of togetherness and solidarity.

Some of those organizations are quite small, so we didn’t want to give them more money than they could cope with, and we also wanted to make sure we had the capacity to support the other things that Jo cared about.

Is that where the idea for the Jo Cox Foundation came from?

Exactly. She had a range of interests that were broadly coherent, but also very diverse, and what we wanted to do was to make sure that we could facilitate people who wanted to take those forward. Our theory of change behind the foundation is not predominantly to raise money, but to build and catalyse networks of influential, well-connected, creative people from across her range of interests, so we’re working on a number of those themes – loneliness, Syria, protecting civilians in armed conflict, women in public life, family-friendly parliament and autism.

For each of them, we’ve got a group of Jo’s friends or colleagues who are driving forward individual approaches. The work that’s most developed is the work around loneliness. Jo had put together a commission before she died, with the aim of galvanizing public engagement around it, but also thinking about what sort of policies are needed, and what the way forward is.

Rachel Reeves and Sima Kennedy, a Tory and a Labour MP, are taking that forward and it’s being called the Jo Cox Loneliness Commission. It’s backed by all of the major players.

What we want to do is make sure that we suck every last opportunity for impact on the work that Jo cared about. If it becomes harder in three or four years’ time, we’ll do things in a different way.

Did the foundation’s approach of being a catalyst and facilitator come out of discussion with friends and family?

Having worked in the past with trusts and foundations, I didn’t want it just to be a monument to Jo, which she certainly wouldn’t have wanted. I wanted it to be very action-oriented, to be light, rather than cumbersome with a huge bureaucracy, and I didn’t want to spend all my time fundraising.

We’re not trying to set up something that will be there in a 100 years. If it is there in 100 years, because there’s goodwill and we seem to be having impact, then that’s fine. But if we’re there for three years, that’s also fine, as long in that time, we advance the issues.

You talk about the foundation’s basis being the catalyst of goodwill rather than money. I understand it was set up and registered as a UK charity very quickly. Is that an example of the goodwill that you’ve encountered – of people really wanting to back what the foundation stands for?

Absolutely. Our office space is donated, the legal work was taken forward by a firm of lawyers on a pro bono basis, and they did it in record time. It’s been very much a snowball rolling down the hill and gathering momentum.

Obviously that won’t always be the case, but what we want to do is make sure that we suck every last opportunity for impact on the work that Jo cared about. If it becomes harder in three or four years’ time, we’ll do things in a different way.

In a sense, the foundation’s work builds on the work you’ve been doing for years – countering populism and nationalism?

Yes, the work I was doing on building open and inclusive communities predated what happened. We were in the middle of creating a new organization to take that work forward, and that will be happening in the next couple of months, funded by a host of different donors and philanthropists, who funded our initial research work around this theme as well. It seemed appropriate to ensure that work was separate from the work of the foundation in terms of governance and finance.

Obviously there’s a lot of overlap but there are also clear differences. My co-founder, Tim Dixon, and I spent almost two years researching eight European countries – the UK, Italy, France, Germany, Greece, Poland, Sweden and the Netherlands – how otherness, populism etc was shaping politics and how well placed civil society was in each of those countries to respond to this threat.

What prompted that work in the beginning was a sense that the refugee crisis was going to play out in an already divisive environment, and it was going to accelerate the far-right’s gaining prominence.

Also, what became clear pretty much immediately is that this isn’t about any individual demographic group, it’s about otherness, which is different in different circumstances.

Actually what we need to do is try to break down perceptions of otherness, rather than doing it group by group.

On one side, civil society seems very fragmented. You have groups working on anti-semitism, separate groups on Islamophobia, you have another set of groups working on LGBT rights etc, while, on the extreme right, you have this integrated force taking forward prejudice and hatred and going after group after group.

What that means is the strength of the pro-diversity, pro-community force is split, while those who are popularizing hatred are not big, they’re just better organized.

What that means is the strength of the pro-diversity, pro-community force is split, while those who are popularizing hatred are not big, they’re just better organized.

Why do you think that is?

From our research, what’s really clear is that the populists communicate emotion, and they tell stories, whereas the political centre talk about myth-busting and facts, and spend a lot of time trying to rebut individual claims. They don’t tell stories. Look at the effect of the death of Aylan Kurdi on the beach. That was a story, rather than a statistic, and had a very demonstrable impact on public opinion. I think another reason is probably about where the funding comes from.

Funders supporting pro-diversity groups often very carefully delineate their funding and do so in increasingly niche areas, whereas nobody really builds the broader themes about commonality and tolerance. Whereas when the Russians fund the far-right, they are doing so to popularize a theme of intolerance, of otherness.

They don’t really care how they do it, and that gives them some flexibility. If you look for example at the BNP, it went from hating black people to saying ‘actually black people aren’t too bad, it’s Muslims that are the problem’, to saying ‘it’s Muslims and migrants’, so the individual theme changes.

Rather than talking about tolerance and diversity, the starting point would be community. That’s the thing that would unite probably 70 to 80 per cent of the population.

From what you said, narrative and language are really important and there’s work to be done there. How do you think the centre can get more of a purchase in public opinion?

As part of our research, we did a series of detailed segmentation polls in some of the key countries – France and Germany in particular, and we’re currently doing it in Italy and Greece – and what we took from it is that there are five gaps that need to be filled.

In most of the countries, there’s a very significant gap in terms of what the narratives are that work, particularly with swing demographic groups. It’s done quite well in the UK by groups like Hope Not Hate and British Future, but in most other countries it isn’t done to that level of sophistication.

Second, there’s a really important piece of work to do directly with political parties, centre-left and centre-right, about how they can avoid ending up in a situation like France, where you ignore the rise of the far-right for a long time, then you ape its rhetoric without any of the authenticity, and the political party, in the case of the socialists, is abolished.

Third, we need campaigns that target those roughly 50 per cent in most countries who are anxious – they’re not racist, they’re not Islamophobic, but they are worried about otherness, whether it’s because of the economy or whatever. Nobody spends any time talking to that group. They are left to the extremes. Political parties engage with them at election time but they don’t engage with them more broadly. And we know the messages that work with them, we know the themes, we know the way of talking about these issues that reassures and reduces that sense of alienation.

Fourth, how do we activate the existing coalition of support? Because we’ve got unbelievably powerful allies, whether that’s the trade unions and the big businesses, the football clubs and the faith groups, we’ve got all sorts of cultural monoliths that are broadly on our side in this debate.

But their support is latent?

Exactly, and we think the reason is because of the political risk and because that’s not the game they’re in. Football clubs play football, they don’t do politics. We think that by giving them a strategy that they could dock into, we could give them some confidence and also reduce the risk because they will be part of a group, they’re not doing it by themselves.

Finally, how do we build this sense of community at a much more grassroots level? So rather than talking about tolerance and diversity, the starting point would be community. That’s the thing that would unite probably 70 to 80 per cent of the population who worry that they don’t live in close enough communities now.

There’s a big opportunity to really emphasize local community building. So those are the five things that we’re looking at.

The narrative is important, but just as important is the insight that Jo talked about a lot, which is to talk less about difference, and more about commonality. Liberals, progressives, centrists spend a lot of time talking about how great it is there’s difference and diversity, and that’s not a bad thing, but actually to that anxious middle it’s often very alienating, because it’s change that worries them. Let’s talk about the things we have in common.

So is the hashtag, #MoreInCommon, your attempt to find the word that brings together the left and the right?

It comes from Jo’s maiden speech in the House of Commons and her analysis of community. We’ve found a lot of reasons to talk about difference, but very few to celebrate what we have in common. The Great Get Together that we’re organizing in the UK at the moment is an opportunity to do exactly that.

It’s on 17 and 18 June, isn’t it? How many people are expected to be involved?

We have 10 million people taking part in the UK, which is a lot. It’s the anniversary of Jo’s murder and it’s partly about remembering who she was and that her politics really came from a sense of community, but she’d hate the idea of people lighting candles and being in mourning for her, she’d want her death to bring people together.

So we’re asking people to get together with their neighbours, share food with them and celebrate what we have in common. It’s a very basic proposition.

The partners involved are very diverse – the Countryside Alliance, the RSPB, the Trades Union Congress, the Confederation of British Industry, English Heritage, the Premier League, all of the major NGOs, Oxfam, Red Cross, Save the Children, NSPCC.

There is an incredible swathe of support, and the reason we’ve managed to build that coalition, but also the reason that we’re so optimistic about scale, is because I think the political and media rhetoric of division and animosity isn’t shared by the public. I think probably 75 per cent of them are just sick of that. They might have voted particular ways in elections or referendums, but it’s not the only thing that defines them. Most people aren’t spending all the time obsessing about Brexit.

So in spite of the dark background against which this is set, you are optimistic?

Yes. I’m very optimistic, and Jo was, too, that intrinsically people are good and we just need to give them opportunities for that goodness to come out. The reason we live in societies is that people value their communities, they value society, and what we need to do is to find more excuses to celebrate that.

Do you think there’s something about philanthropy being private action for the public good which embodies that?

Do you think there’s something about philanthropy being private action for the public good which embodies that?

Yes. I hope the Great Get Together is one of those moments where the public draws breath and sits back for a second, and realizes that we have more in common than that which divides us. And I hope it will have a longer-term legacy of making communities think more about themselves and even do things together on local issues, whether that is street lighting or loneliness – whatever it is.

Brendan Cox was interviewed by Alliance editor Charles Keidan.

Comments (0)