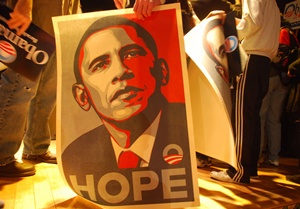

Ever since it became clear that Barack Obama would be the next president of the United States, there has been an unprecedented euphoria among civil society and philanthropy practitioners. Not since these practitioners began to sense themselves a genuine sector of society taking their place alongside the public sector and the for-profit sector almost 40 years ago have we seen this kind of excitement. The promise of unlimited access and substantial influence can almost be tasted. What I fear, however, is that the expectation is too high to be realized and there will be eventual disappointment on the part of civil society and defensiveness on the part of government.

I say this because of the rapidity with which one’s mindset can change when one’s institutional base changes. When I started working for the Ford Foundation in 1971, it was in their Indonesia field office. Although that office accounted for less than 3 per cent of the foundation’s annual budget, my distinct impression was that the headquarters in New York existed essentially to support the work of our field office and its staff. Parts of many staff meetings were spent criticizing the latest unreasonable request from New York and bemoaning headquarters’ inability to understand the local context within which we operated.

When I returned from Indonesia to work at headquarters in New York after five years, I was stunned at how quickly my mindset and perspective changed. I may not have fully understood the change or the rapidity with which it happened immediately, but with the benefit of hindsight, I knew that it did happen. Almost at once, I started being critical of the field for its parochial vision, for its inability to see the forest from the trees, for its refusal to see broader trends at work globally. Needless to say, what changed was neither headquarters nor the field office but rather where I was institutionally embedded. Many see this centre-field tension as a productive tension that spurs innovation and improves programmes.

When I returned from Indonesia to work at headquarters in New York after five years, I was stunned at how quickly my mindset and perspective changed. I may not have fully understood the change or the rapidity with which it happened immediately, but with the benefit of hindsight, I knew that it did happen. Almost at once, I started being critical of the field for its parochial vision, for its inability to see the forest from the trees, for its refusal to see broader trends at work globally. Needless to say, what changed was neither headquarters nor the field office but rather where I was institutionally embedded. Many see this centre-field tension as a productive tension that spurs innovation and improves programmes.

I bring this up because what tends to happen is that we assess the actors going into government, and particularly the ones going into the administration, by what they did and said before they became part of the administration. By that measure, the expectation of unlimited access and substantial influence seems reasonable. The reality, however, is that once these people take up their new positions, their mindset and perspectives will change dramatically. They will begin to feel besieged, to feel that they are not being given the space to perform, that their civil society colleagues do not fully grasp the issues they face. For their part, civil society actors will feel betrayed and will begin to be critical of programmes and policies, engendering defensiveness from the public sector.

Some regimes are friendlier than others towards civil society and one measure of this may be where the staff for the administration is drawn from. There is no doubt that the programmes and policies of the current administration are more in tune with a broad swath of civil society than was the case with the previous administration. But while the euphoria was perhaps not as heightened, when the Clinton administration entered office there was also a feeling on the part of civil society that it would have increased access and influence. While the policy goals of the Clinton administration were more in line with those of the lion’s share of civil society, the means were not necessarily so, and the promised enhanced access turned out to be rather superficial. This ignited the usual criticism, which produced a defensiveness syndrome.

This is the natural order of things. Government and civil society have a love/hate relationship. At one time or another, it may be a little more love than hate or the other way around. As long as civil society is concentrating on the safe activities of providing services, enhancing education or supporting the arts, all governments tend to support it. When civil society moves to the edgier things like advocacy, human rights and social justice, only more mature democracies stay the course.

That is because civil society plays a role far greater than the instrumental activities it performs. As a sector, it provides another layer of institutions that make it more difficult to concentrate and abuse power – a kind of Fifth Estate, if you will. As such, it should recognize that it will always be uncomfortable in bed with the public sector because an important part of its role is to keep that sector’s feet to the fire. The public sector, for its part, needs to suck it up and understand this role of civil society.

Barry D Gaberman can be contacted at bgaberman@gmail.com

Comments (0)