Delwin Roy’s column for the March issue of Alliance contained a review of Jem Bendell’s new book Terms for Endearment: Business, NGOs and sustainable development. Bendell’s central thesis is that NGO campaigns are constituting ‘a new and emerging form of regulation for international corporations, called civil regulation’ – a thesis that Roy finds ‘a bit disturbing’. Who regulates these new regulators? Here Jem Bendell and Delwin Roy continue the conversation.

Jem Bendell

Why did I want to advance the idea of ‘civil regulation’? Simply because the new fashion of voluntarism is anti-democratic. The existence of win-wins in certain cases should not lead us to assume that for-profit organizations will always act in the public interest. Standards for economic activity need to be discussed and established, at least to a degree, separately from commercial interests in that economic activity. The old idea was that government provided this function. But now?

Non-profit organizations working solely in the public interest (this does unfortunately discount an increasing number of NGOs) are seen by society as having something valid to say by the very fact that they are non-profit (opinion polls across Europe show this). This isn’t frightening. On the contrary, I find the converse view – that for-profit/non-profit status has no bearing on an organization’s articulation with matters of the common good – to be frightening.

Much of my work at the New Academy of Business is about breaking down the ‘compartmentality’ of managers where morality is left at home, but the fact remains that most companies are the legal property of shareholders, mostly seeking maximum returns. This governs the way managers can incorporate their values into their work.

Where does this leave CSR and corporate citizenship? The conclusion to my book talks about a more radical version of corporate citizenship, which upholds democracy. But that means giving up some control, and companies don’t do that willingly. History teaches us they have to be pushed. Hence the uncomfortably confrontational language you highlight in the book.

Delwin Roy

I think you ought to consider what a ‘workable partnership’ with corporations needs to entail. A shift of decisive power in the negotiation of partnership – from corporations to NGOs – somewhat belies the intent of partnership. We have all read tracts on the unfettered power of large corporations. Is it so unrealistic, then, that one might wish to raise questions about the possible negative effects of that same concentration of power in NGOs?

I have just returned from Malawi, one of the poorest countries in the world. NGOs abound, but one would be hard put to find a local, community-based, Malawian-led NGO. It seems that many NGOs are happy in their role presiding over the poor and black African. Most are no doubt well intentioned, and would qualify for your designation as the ‘new civil regulators’, but should they qualify if they do not have in their governance representation and leadership drawn from what I call ‘the community of the affected and afflicted’?

I am currently establishing a fund to support education in Africa, a memorial to my son, killed in an accident in South Africa last year. A major aim of this is to incorporate in the company in which I have now inherited a sizeable ownership a sense of corporate responsibility – and, in so doing, to try to mobilize the indigenous and multinational business communities to create indigenous foundations to enable the community to address its own problems. So far, the response has been good. I’m also seeking NGO partners for the fund, but a partnership in the vein of which I have spoken.

Jem Bendell

I am also concerned that the NGOs with the most sway over corporations are those based in the West. Companies’ concerns about bad publicity have led to codes of conduct that focus on emotive issues such as child labour rather than issues of primary concern to workers and their communities such as pay, conditions and freedom of association. However, we are seeing more mature approaches from NGOs as they begin to act as loudspeakers for workers and communities in the South. One example was the campaign by the World Development Movement and Bananalink to bring consumer attention to the concerns of the unions and NGOs in Costa Rica involved in the banana trade. There are still some NGOs who assume a moral authority in their own right rather than acting as channels for the disempowered to have their views heard. We are right to question this.

It’s heartening that companies in Malawi are responding well to your attempts to engage them in helping poor people to help themselves. But we shouldn’t forget the root causes of their poverty. Malawi is a poor country in part because its main exports are tobacco, sugar, tea and coffee, which are traded in grossly unequal terms with Northern businesses. Fairtrade is one answer, but I don’t see any companies prepared to change the terms of trade with their suppliers. Let’s recognize the limits of the ‘win-wins’ between corporates and society. Although NGOs and businesses may cooperate on specific projects, they may still have fundamentally different visions of the future.

I don’t think that we can rely on companies to evolve towards corporate citizenship of their own accord. Until recently an annual course of HIV/AIDS drugs cost thousands of dollars. It was only after campaigns by UN agencies and NGOs like Medecins Sans Frontieres that Merck and Bristol Myers-Squibb (BMS) announced in March that they were cutting the cost of their treatments. Before we start considering this to be corporate citizenship, let’s not forget that 39 international pharmaceutical companies, including BMS, went to the Pretoria High Court that same month to challenge a South African law aimed at easing access to AIDS drugs.[1] It still seems that to some pharmaceutical companies you don’t count as a human being unless you’re a human buying.

Delwin Roy

TNCs mobilize vast resources across borders and cultures. This is a fact and a given. My question is how do you make it civil? How do you give it a ‘human’ face? We catalogue its shortcomings endlessly, as though the negative message will somehow inspire it to be other than it is. There are corporate voices heard in response. A good friend of mind, a CEO of a multinational, once said to me: ‘Del; I don’t know too many CEOs who sit around trying to figure out how best to be “irresponsible”.’

Why, then, is it that the NGO community finds it so terribly hard to understand that corporations are in fact ‘peopled’ with individuals with ethics, values, opinions?

Only recently, when approaching an NGO as someone trying to build a corporate responsibility ethic in a firm, I was treated to the comment, ‘Well, you know, NGOs find it very hard to accommodate corporate thinking and private sector methods.’ Yet it was this ‘corporate thinking’ that had just led the private sector entity to seek the NGO’s wisdom and guidance on the matter.

We’re both trying to do the same thing. I just think that my approach may be a bit more flexible in accommodating both points of view, corporate and NGO, for I clearly recognize the need for both. I am just not willing to accord NGOs the position of ‘moral superiority’ that they seem so desperate to occupy.

A footnote from Georg Kell

What would a world with civic regulation look like? What exactly would private corporations be expected to do? Do we really want them to be the caretakers or providers of public goods? And, if so, who would decide what kind of public goods, and for whom?

What we see today is, in essence, an opportunistic race to leverage narrow agendas onto global actors. This is not necessarily ‘bad’ – on the contrary – but, as Jem Bendell says, it is certainly deeply undemocratic. Delwin Roy’s pointed comments on NGOs reinforce this view.

At some point governance issues must be tackled. A good point of departure for such a debate would be the search for an agenda concerning what exactly one should expect from corporations. Working with the United Nations, I have no doubt in my mind that development efforts and global public goods are by far the most important concerns. CSR issues should primarily be aligned with the priority goals established by the international community. Imbalances between the economic, social and environmental spheres are most pronounced at the global level. Alas, the CSR movement is characterized by fragmentation; agendas are narrow and too often national in design. Defining a common agenda is crucial if purpose and direction is to emerge from the current ad hoc approaches.

Business and civil society can both do a lot, individually and collectively, to make a real difference. But the current debate about access to life-saving medicine demonstrates that comprehensive solutions can be found only if all actors work together: governments, business and civil society.

1 The 39 pharmaceutical companies withdrew from their legal action against the South African Government on 19 April in the face of mounting public and government opposition across the world.

Delwin Roy is a consultant on strategies for global corporate community involvement. From 1985 until 1998 he was President and CEO, The Hitachi Foundation. He is now Director, Loita Capital Holdings Africa, based in Johannesburg, and Chairman and CEO, the Eric Edward Roy Fund for Education in Africa (a Washington DC-based non-profit). He can be contacted by email at DARoy@aol.com

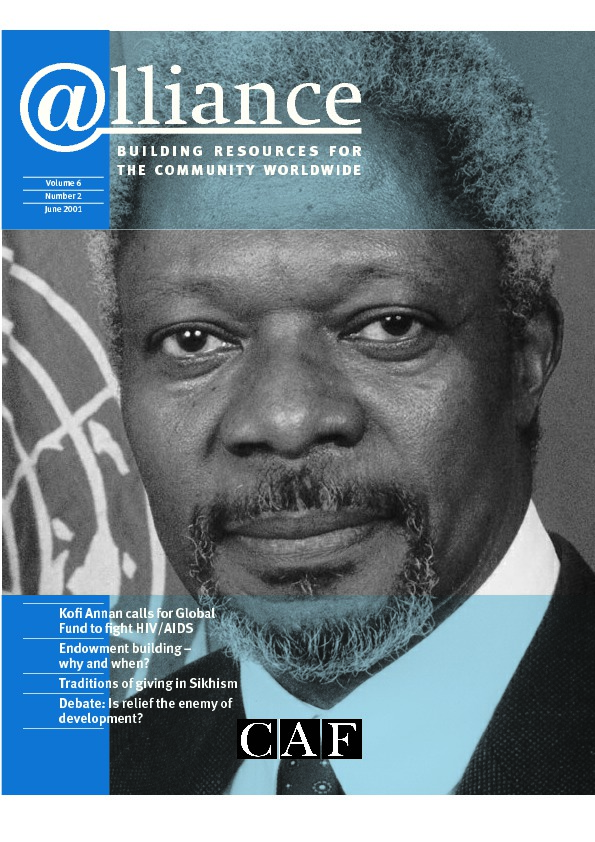

Georg Kell is a senior adviser to Kofi Annan, responsible for devising the Global Compact – see http://www.unglobalcompact.org. He can be contacted at Globalcompact@un.org

Jem Bendell writes, consults and campaigns on issues of corporate social responsibility (CSR). An associate of the New Academy of Business, a progressive business educational organization, his clients have included ILO, INTRAC, DfID and the Rainforest Alliance. Bendell recently founded the CSR recruitment service, Lifeworth.com He can be reached at jembendell@email.com

Terms for Endearment: Business, NGOs and sustainable development is published by Greenleaf Publishing/New Academy of Business. Price £19.95/$40 (paperback).To order visit the Greenleaf website at http://www.greenleaf-publishing.com

These debates are continuing on the business-NGO relations discussion group moderated by Jem Bendell at http://www.mailbase.ac.uk/lists/business-ngo-relations

Comments (0)