It is an odd but interesting fact that local resource mobilisation has never really inspired the interest or support of most funders. Over the years, I have developed a few theories as why this is so.

One reason is impatience. The dominant funding system still favors and rewards the promise of quick – and often, let’s face it, unrealistic – results, in the form of short-term projects and tangible outputs can be easily attributed to specific donors. Building local giving, however – particularly giving for social change – takes time. In fact, getting people to see themselves as having agency and being able to exercise choices by giving – rather than as passive ‘beneficiaries’ – is in itself a form of social change. Establishing and maintaining trust with local donors can also be a gradual process, requiring different forms of accountability from the usual kind of grant reports that land on the desks of distant institutional funders, as is the development of supportive architecture through which resources can flow transparently and of new skill sets (getting your neighbor to give, for example, is rather different from producing a log frame).

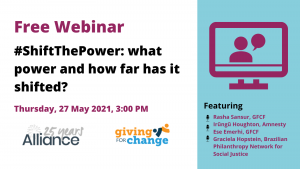

Join Alliance magazine for a conversation on #ShiftthePower 27 May at 3 p.m. BST. Register here.

Another reason is a lingering distrust of ‘ordinary people’ and their readiness or ability to support human rights or social justice, as well as the argument often rolled out by donors and their partners alike that, by accepting local donations, organizations might have to compromise their values (as if those same dynamics don’t accompany most institutional funding).

And then, of course, there is the question of urgency: is local fundraising really a priority at a time of climate crisis or when human rights are being violated?

However, most people working in philanthropy and international development would surely agree that civil society organizations’ over-dependence on external funding has always been – and is becoming increasingly – problematic. The entrenched power dynamics, the ever-changing whims of funders, and general reductions in aid flows are all factors here and when human rights organizations are denounced and criminalized as ‘foreign agents’, reliance on external funding can at times become downright dangerous for those affected. They might also agree that, in the future, the pursuit of equity and justice, of inclusive development, and of the protection and advancement of rights, should all be resourced and led from within countries, and that civil society sectors must be owned, resourced, and defended by engaged and vocal domestic constituencies. Just not yet.

How do you build local? Read a response from Alette van Kralingen, Policy Officer at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of in the Netherlands.

But here’s the thing. Despite all the obstacles, systems and attitudes that seem to discourage donors from focusing on local resource mobilization, change has been happening anyway. In fact, it’s accelerating, and (some) donors are finally starting to pay attention: a new partnership with the Dutch government, Giving for Change, is a great example of this.

The #ShiftThePower hashtag – introduced in Johannesburg in 2016 at the first Global Summit on Community Philanthropy – has accompanied, and cheered-on, and perhaps helped to define some of that change. Our idea was always to use the event to celebrate and shine a light on the new kinds of more democratic and participatory approaches to giving as an important form of civic participation, rights claiming and expressions of empathy, solidarity, and dissent. To focus on ‘development’ as tools and strategies that promote the advancement of trust, dignity and agency, rather than simply the management and administration of external money. Not just as a simple alternative or add-on to the current system, but as part of a broader vision of structural change.

Getting people to see themselves as having agency and being able to exercise choices by giving – rather than as passive ‘beneficiaries’ – is in itself a form of social change.

Since the Summit, we have been particularly interested in the idea of ’emergence’, as reflected in the practices and priorities of our community philanthropy partners and others who are crafting new ways of deciding and doing that nurture energies and resources within the diverse communities they serve and that deliberately seek to break with decades of learnt helplessness towards which donor aid has contributed.

And the broader context for all this is crucial. #ShiftThePower is just one small voice in a much wider global clamor for change. Think of Giving Tuesday, of #MeToo, of recent movements galvanized in Poland (Women Strike) and Nigeria (End SARS), and of last year’s #BlackLivesMatter protests, which saw people from all walks of life express their support for the movement by giving. And think of COVID-19, how international aid failed in so many ways, and how communities all over the world were forced to rely on themselves, their networks and their own resources in ways that were shaped by new forms of mutuality and solidarity.

So what next? It’s fair to point out that many funders have been slow to embrace change, to see the #ShiftThePower movement – like the transformation in, say, the global energy sector, away from giant coal power generators to a looser network of small local wind and solar plants – as an opportunity for truly radical transformation.

But the wind is in our sails.

Jenny Hodgson is Executive Director of the Global Fund for Community Foundations.

Comments (0)