Alliance recently held a webinar on ‘scaling up’ within the sector, sponsored by the H&S Davidson Trust. We were joined by a stellar set of panellists: Ann Mei Chang, a leading expert on social innovation and author of Lean Impact: How to Innovate for Radically Greater Social Good; Yanni Peng, CEO of Narada Foundation, a leading grantmaking foundation based in Beijing; and Maharshi Vaishnav, chief of staff at India’s NGO Educate Girls.

‘Extending a successful social intervention to a much bigger scale often seems like the Holy Grail,’ began Alliance’s associate editor Andrew Milner, chair of the discussion. It has been tested, it works and there are ‘economies of scale’, and you don’t have to go through the labour and expense of starting from scratch. Most beneficial is that a successful initiative can be multiplied many times.

However, there are formidable obstacles: the difficulty of setting reliable measures for social solutions can mean that it’s likewise difficult to tell if scaling up an initiative will really produce the desired results. There is no guarantee therefore that an innovation will work when it is transplanted to an apparently similar set of circumstances, and not all initiatives are suitable for scaling up.

Is it worth it?

Chang kicked off the discussion and began by sharing her own definition of scale, ‘because I think a lot of people mean different things by that word’. Chang believes when talking about scale ‘it’s important to start by anchoring ourselves in the question: what would it look like to truly move the needle on problems that we aim to tackle?’

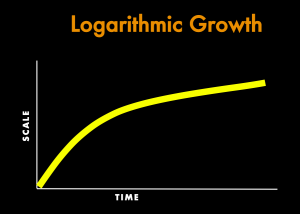

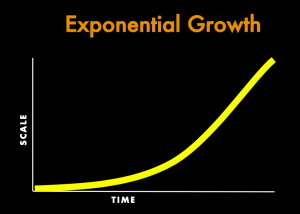

Chang has found that when the focus is on short-term delivery rather than long-term scale, ‘we can experience this initial burst of interest as funders are drawn to an exciting new idea, and then we find that our trajectory flattens out over time as we start reaching the limits of philanthropy.’ This results in an all-too-common fall that is far short of the actual scale of the need.

Chang has found that when the focus is on short-term delivery rather than long-term scale, ‘we can experience this initial burst of interest as funders are drawn to an exciting new idea, and then we find that our trajectory flattens out over time as we start reaching the limits of philanthropy.’ This results in an all-too-common fall that is far short of the actual scale of the need.

Contrast to this, Chang believes that if we’re serious about scaling then it’s important to pay more attention to the slope of the exponential curve than the number of people we reach. ‘That is, do we have an engine that will not only sustain, but accelerate, growth over time? In this case, progress may initially seem slow as you test, iterate and search for a scalable and sustainable approach, because this involves reducing cost and complexity, increasing efficacy and identifying a renewable source of funding such as a host country government or private market, that can allow us to then ramp up that curve and really accelerate growth over time.’

Contrast to this, Chang believes that if we’re serious about scaling then it’s important to pay more attention to the slope of the exponential curve than the number of people we reach. ‘That is, do we have an engine that will not only sustain, but accelerate, growth over time? In this case, progress may initially seem slow as you test, iterate and search for a scalable and sustainable approach, because this involves reducing cost and complexity, increasing efficacy and identifying a renewable source of funding such as a host country government or private market, that can allow us to then ramp up that curve and really accelerate growth over time.’

Chang shared a successful example of a pathway to scale through VisionSpring, a social enterprise providing affordable eyeglasses, in a world where 2.5 billion people need but don’t have them. VisionSpring started by distributing glasses through their ‘vision entrepreneurs’, but quickly realised they were losing money on every pair of distributed eyeglasses. In their first pivot, they used higher-end sales in more urban areas to cross-subsidise outreach to more rural, poorer areas – ‘but they realised it was going to take decades to build the infrastructure necessary to provide these kinds of services around the world.’ In their second pivot, they leveraged their existing network with BRAC in Bangladesh, and used BRAC’s network of healthcare workers to distribute over a million pairs of glasses, and through hundreds of other partnerships around the world, a total of almost seven million.’ Impressive, but nowhere near the 2.5 billion number needed. Most recently, VisionSpring has established the EYElliance, ‘a public-private partnership that brings together companies, non-profits and governments to address the systems issues behind the market and policy failures that have led to this situation.’ An early success has been an MOU signed with the Liberian government to integrate vision screening into public health systems and schools.

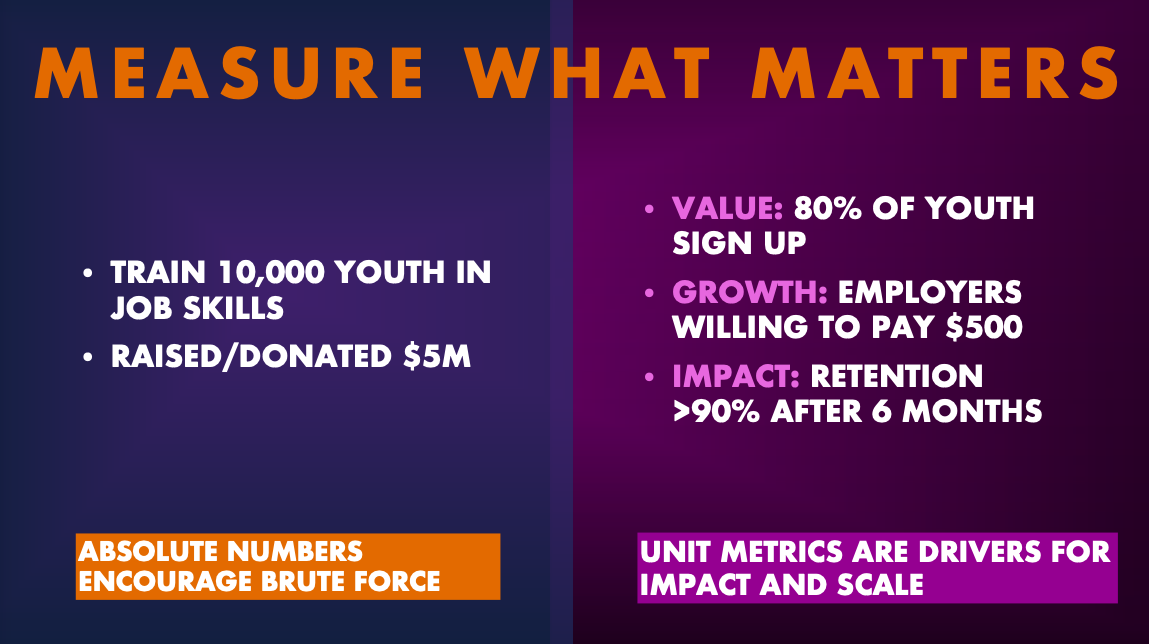

Following on from this, for Chang it’s important to hold onto solutions ‘more lightly, and look to the data to figure out what’s most effective.’ Absolute numbers – how many people have we reached? How much money have we raised? – are what Chang terms as ‘vanity metrics’, because while they sound fantastic, it doesn’t tell us whether we’ve made a difference. Rather, the important metrics are unit ones: for every 100 people reached, what was the adoption/persistence/success rate? The unit cost? ‘When we test and optimise for those unit-level drives of success across value, growth and impact, they’ll pay dividends over time.’ Eliminating basic risks means delivering something more comprehensive to more people. ‘The goal is, if we’re going to fail, we want to fail as small as possible, and ironically it’s scaling too fast that often prevents us from fully scaling to the extent that we need over time.’

Peng was next to speak, sharing her foundation’s learning on building infrastructure for scaling in China using the Effective Philanthropy Multiplier (EPM).

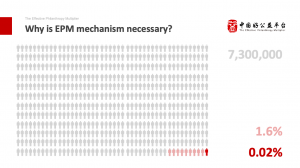

Peng began by talking about why this infrastructure was built – there are currently 7.3 million adults in China with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Yet only 1.6 per cent can expect access to services such as day care. China’s largest NGO working in this area provides services to just 0.02 per cent of adults affected. ‘We can see there is a huge gap between the supply and the need.’

Peng began by talking about why this infrastructure was built – there are currently 7.3 million adults in China with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Yet only 1.6 per cent can expect access to services such as day care. China’s largest NGO working in this area provides services to just 0.02 per cent of adults affected. ‘We can see there is a huge gap between the supply and the need.’

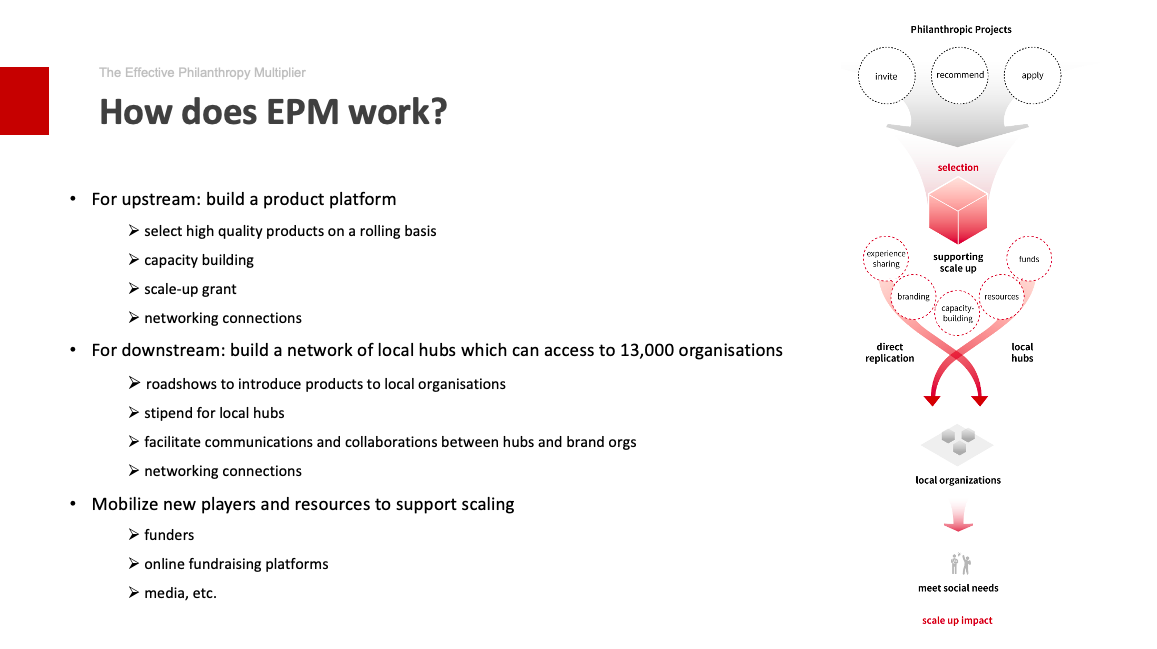

In building the EPM platform, three gaps were identified. Firstly, while there were effective philanthropy solutions, the NGOs typically lacked the capacity, network and the resources to scale up their services.

Secondly, a lot of new NGOs are being set up – in 2016 when this platform was being built, there were 800,000 NGOs in China, the majority of them built in the last 10 years. Those set up at company level ‘are very keen to provide services and do things to meet local needs, but they lack the knowledge of how to do ground-up projects, and how to design products to serve local needs.’ In the last six years, the Chinese government has also begun to procure services from NGOs, resulting in larger and larger budgets for department spending.

Extending a successful social intervention to a much bigger scale often seems like the Holy Grail.

Thirdly, there are increasing numbers of corporate start-ups with large CSR budgets – ‘but they also have difficulty in identifying good projects, so we decided to design this platform to join these three parts together… and join supply with need.’ Over the last four years, hundreds of projects have been selected for the EPM platform, with very strict due diligence processes. Uniquely, ‘when they’re selected, we will do capacity building and also provide small scale grants to support their scale up, and also we plug them into our network of other NGOs, to other funders and to other players in this sector.’ They have also built 39 ‘local hubs’, centres with a close relationship to central government, who are also linked with local NGOs. Through them, there’s access to 13,000 NGOs, schools and local voluntary organisations in China.

The Narada Foundation works with these hubs to run ‘roadshows’ at local level, providing a small stipend and bringing EPM projects to cities and introducing both products and solutions to local organisations.

There are currently 59 projects on the EPM platform, across eight thematic areas: education, environment protection, health and safety, community development, service to the elderly, service to people with special needs, gender and rural development. These projects cover every Chinese province and two thirds of China’s counties. With over 56,000 replications by local partners, an estimated 65 billion people are benefiting from them. Pre-platform, the projects ‘lacked the opportunity to get in touch with local partners, because they don’t have enough channels to reach local organisations. Even when they had the opportunity to get to know them, it’s very hard to find enough funding to sustain services at a local level, even when in a lot of cases when local partners rely on central funding. When they try to scale up it’s very difficult to raise money for a bigger and bigger network of operations. One of the difficulties for replication is to find sustainable funding for local delivery. Because local hubs joined the EPM, they have played a very effective role in terms of leveraging local funding and therefore makes replication feasible.’

Vaishnav was last to present on behalf of Educate Girls (EG), who over the last 13 years have worked in over 18,000 of the most rural and remote villages of India to enrols out-of-school girls and looks to ensure they remain in school and support them while they learn.

‘The first five years went into getting the concept off the ground, where the founder started with a small pilot in 50 villages and demonstrated the result.’ The government then required proof of concept for 500 villages, which they then did. ‘We only operate in the public school system in very rural, very remote, very underserved geographies of India. The reason why we do this is because India has something called the “Right to Education Act”. This basically guarantees a school in every village, and that’s the infrastructure we wish to leverage.’

‘In 2021,’ said Vaishnav, ‘India is one of the fastest growing economies in the world… but female literacy in India is at 64 per cent, and there are 4 million girls who are out of school. In the geographies where we operate in, 67 per cent of girls are child brides and of the 100 per cent of people who are trafficked in India, 76 per cent of women and girls.’ There is a dire need for women and girls to be educated, and is the reason for EG’s existence. How does this then happen? They go door-to-door, with their own census, identifying girls who are out of school. Once identified, there is extensive counselling and dialogue with both the parents, and the community – ‘because oftentimes it’s the community that inhibits a girl’s education, largely because of patriarchy.’

EG has observed that girls are out of school because of two P’s: patriarchy and poverty. From the ‘age-old discriminatory practices right across the board, from a girl being allowed to be born, to education, to higher education, employability, marriage, etc… and the severe marginalisation of poverty.’ Therefore EG’s model works at the behaviour and mindset level, as well as the systemic.

From 50 villages in 2007 to 19,000 in 2021, EG has essentially doubled almost every two years, enrolling over 800,000 identified girls and improving the learning outcomes of over one million across three states – Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. Quality was not a casualty in their growth, due to creating the world’s first Development Impact Bond (DIB) with UBS Optimus Foundation and Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF). There were two distinct outcomes: increase the enrolment of out-of-school girls, and to demonstrate improved learning in Hindi, English and maths, with the target as aggregate learning gains. A small contract with no template from which to emulate, it ran from 2015-2018, working with over 7,000 children in 166 schools and the contract size was about $270,000.

After these three years, 160 per cent of learning targets were delivered and against a 79 per cent target of 613 out-of-school girls identified, they enrolled 768 girls, ‘thereby demonstrating that delivering or achieving quality at scale is a possibility.’ EG then worked with their technology and analytics partner IDinsight to create an algorithm to help identify villages with a higher-than-normal propensity for girl-child exclusion. Now the hypothesis is ‘to target only 5 per cent of villages in India, so out of 670,000 we’re going to target around 35,000 villages, that hold up to 40 per cent of India’s out-of-school girls. We’re targeting 1.56 million girls.’ This has helped EG to ‘pivot from a 100 per cent saturation model to a ‘hot spot’/’high incidence’ rate villages only with the highest concentration of out-of-school girls. This in a way help us expedite impact, optimise resources and enhance operational efficiencies.’

The five-year goal from 2019-2024 is to enrol 1.5 million girls, retain over 1.3 million, to improve the learning outcomes for over 900,000 and provide life skills training to over 70,000 adolescent girls. ‘At the same time, we will also work on school governance and infrastructure across all the schools that we’ll be operational in – that’s 40,000 schools. Over a 5 year period our total budget will be over $100 million.’

Milner followed up on Vaishnav’s presentation, asking if Covid-19 had subjected EG to extra pressures as a classroom-focused charity. ‘Girls and women in India were the worst hit by the pandemic,’ replied Vaishnav. ‘For two reasons: one was because all access to public services, public goods, came to a halt because of our extensive lockdown. And the second most important thing is that a lot of men and boys returned home, with reverse migration. Therefore it became a lot more difficult for us and also a lot more important for us that we kept in touch with these girls throughout.’ The first six months of the pandemic were spent ensuring that the girls were safe and providing relief supplies, and the last six months ‘we have spent running community-based learning centres to ensure that they don’t miss out on school.’

Small is beautiful, but big is necessary.

Milner then turned to DIBs. Other than the ‘payment by results’ incentive, were there any other aspects of that sort of funding which were valuable? Vaishnav responded that the money was unrestricted, ‘so for us it was a grant.’ As the organisation wasn’t accustomed to delivering outcomes, ‘it radically altered the DNA of our system.’ Pre-2015, EG was very activities-focused, and they had to both unlearn and relearn to focus on outcomes and become ‘activities-agnostic’. The advantages are especially noticeable at present. ‘As we speak, community-based learning has happened because the outcome was to improve the literacy and numeracy levels of children. The focus isn’t on running and delivering curriculum in the classroom. Had that been the focus, then we would have waited for the schools to re-open.’ Through the shifted perspective, they were able to operate and maintain community centres across villages, with basic social distancing and hygiene, to reach those most marginalised.

Chang then followed up, agreeing that the DIB forced EG to really focus on key metrics, which is a ‘really good way to align incentives.’ That said, Chang acknowledged that DIBs ‘are incredibly complicated, there’s a lot of overhead.’ The right incentives aren’t only available through these bonds. We need ‘to encourage organisations to track, to gather data… to encourage improvements in some of these unit-level metrics without having it necessarily structured as a DIB. I don’t feel you necessarily have to have that mechanism in order to get that result, but I think the result speaks for itself in terms of the progress that was made.’

Questions were now brought in from the audience. Hugh Davidson (H&S Davidson Trust) noted that there seem to be many successful initiatives around the world, often run by smaller organizations but few ever seem to be scaled. What are the main barriers to scaling through other, often much larger, organizations?

Chang replied that it’s a very complicated issue, but a lot of it comes down to funding. A large part of the driver for NGOs is to run programs where ‘they’re encouraged to deliver some sort of intervention to some number of people in order to fulfil a grant they receive.’ Winning those grants often comes down to the ‘unique value add’ that these NGOs have, resulting in a reluctance to adopt innovations from third parties. While it’s possible – such as through Chang’s earlier example of the partnership between VisionSpring and BRAC – ‘I think we both need to encourage the large INGOs to stretch themselves to do this, but we also need the funders to really encourage it as well… Some of the new innovations coming out of social enterprises are the best way to get there, but that’s not the incentive system that these organisations work under.’

Jim Riker then asked how to design scaling processes with serendipity in mind – that is to say, how do you position your efforts to expect the unexpected and gain valuable perspectives? Peng responded that scaling up doesn’t necessarily have to mean excluding new things. In China, local partners have access to many beneficiaries who can work in different contexts across different provinces, resulting in local NGOs having their own innovations. ‘This means the project can be refined more openly and more frequently.’

Vaishnav answered that EG haven’t always hit the mark, such as relying on inaccurate data. This has meant coming to find a balance. ‘If 90 per cent of our scaling up has been to geographies with the greatest need for the target constituency which requires our kind of intervention where there are no other civil society orgs then we are fine. We’ll do our best in that 90 per cent, and we’ll leave room for 5-10 per cent of geographies where we may end up purely because of other serendipitous reasons.’ However there’s always room for either the system not necessarily delivering, or a hostile community, or another aspect which doesn’t go how it is expected to. ‘I think we have to learn to live with it.’

The last word came from Chang, with a quote from Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, founder of BRAC: ‘Small is beautiful, but big is necessary.’

Amy McGoldrick is the Marketing, Advertising & Events Manager at Alliance.

Watch a recording of the full webinar below:

This webinar was sponsored by the H&S Davidson Trust

Comments (2)

As a result, there is no assurance that an invention would succeed in a seemingly comparable set of conditions, and not all ventures are suited for scaling up.

At the risk of being too blunt and simplistic, here is the essential problemas I see it: Generally life is a parasite/host dynamic. Men are the parasites. Science proves this. Women must dominate to control parasite load and prevent male destruction. Woman is in charge of evolution, not man. Obviously humans are living in opposition to this natural dynamic, and most are too ignorant to notice that man is a parasite and that he is destroying the Earth host and all else. Man is not going to give any power to woman, to Earth, or to any of his fellow creatures. Man is a parasite, and parasites have no conscience. Unless all men can become like Ghandi, there is no hope.