Climate change amplifies virtually every global challenge – war, migration, drought, disease, food insecurity and poverty. It will transform the arts, culture and education, and shape human progress. Philanthropy faces a historic moment where we must collectively and convincingly respond. One powerful way we can do this is by divesting from fossil fuels and investing in solutions to global warming.

The historic Paris Agreement set an ambitious target of zero net carbon emissions by 2050. The incontrovertible consequence of this commitment is that three-quarters of known fossil fuel reserves must stay in the ground. The agreement is a blaring market signal that the energy base of our global economy can and must change.

But the pace of change is not nearly fast enough. Renewable energy is growing and the fossil fuel era is winding down, but the transition to a zero-carbon economy is dangerously obstructed by the powerful interests of fossil fuel companies. The biggest companies not only refuse to put the brakes on fossil fuel use, they are shifting into high gear with reckless exploration for new reserves. Don’t be fooled by announcements of investment in renewables – they pale into insignificance alongside capital spend on fossil fuels. Their current plans would take the world well beyond 3°C with devastating effects for humanity.

Governments cannot accelerate the transition to a zero-carbon economy alone. Dramatic, ambitious action is required by the private and non-profit sectors. Philanthropy needs to play a critical role through both its grants and its investments. In an open letter, the presidents of the Hewlett and Packard Foundations cite an urgent need for more philanthropic resources to fight climate change. But they refer to grants only. We have many more tools at our disposal.

‘Philanthropies from around the world representing over $12 billion in assets have pledged to divest from fossil fuels and invest their assets in climate solutions, including renewable energy, energy efficiency, clean tech and energy access.’

Strategic use of philanthropic investments

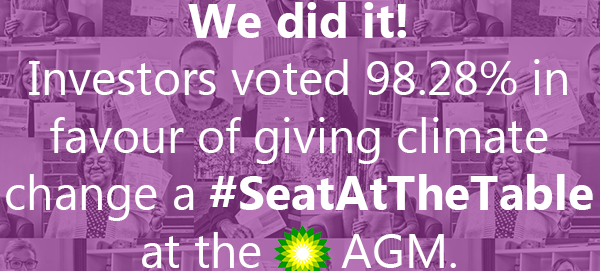

One major tool is the strategic use of investments – the approximately 95 per cent of a foundation’s assets that are not spent on grants or programmes. Divest-Invest Philanthropy was established to catalyse this. Philanthropies from around the world representing over $12 billion in assets have pledged to divest from fossil fuels and invest their assets in climate solutions, including renewable energy, energy efficiency, clean tech and energy access. And in recognition that philanthropy can take a lead, the 140 signatories of Divest-Invest Philanthropy were awarded the Nelson Mandela-Graça Machel Innovation Award for Brave Philanthropy in April 2016.

With this commitment, philanthropy joins the global grassroots movement calling on churches, cities, universities, pension funds, insurers and other institutional investors to divest from fossil fuels and invest in the future. Born on campuses in the US, the movement has exploded globally, spreading to virtually every sector. Today, institutional investors with over $3.4 trillion in assets under management have made explicit commitments to some form of fossil fuel divestment. The global divest-invest movement was cited by Christiana Figueres, executive secretary of the UN FCCC – the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – as a primary driver of success at the climate talks in Paris last December.

The case for divestment/investment is both ethical and financial – and fiduciary.

The ethical case

The ethical argument is a simple one: it is wrong to invest in an industry whose business model is predicated on driving climate change and its harmful impact on the people and the planet. We have a duty to be responsive to the global grassroots movement, doing our part to meet the Paris promise, helping move markets and accelerate solutions. We have a duty to align our efforts with those of our grantees and not the industry driving the problem – one that funded denial of climate science for over 30 years and that today refuses to tender plans to keep the world at the level of warming to which all the world’s governments have agreed.

‘We have a duty to align our efforts with those of our grantees and not the industry driving the problem.’

The financial case

The second argument is financial: investors in coal have already felt the burn of supporting a dying industry. This is just a prelude to similar losses in the oil and gas sector as we electrify our power, transportation and industrial sectors with more affordable renewable energy. The Paris Agreement validates analysis by UK think-tank Carbon Tracker and University College London that most fossil fuels cannot be burned. They are stranded assets whose full economic value will not be realized. Yet the industry counts those reserves on its balance sheets, exposing investors to a carbon bubble recently quantified at more than $1 trillion. Lord Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury and most senior bishop in the Church of England, has called for Cambridge University to divest from fossil fuels, citing the pragmatic, financial case as solid as the moral one.

Policy signals to keep fossil fuels in the ground are intensifying. Over 40 countries and subnational governments have some form of carbon pricing on their books; 90 national governments include carbon pricing as a mechanism for meeting their Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) under the Paris treaty. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund are now advocating that all parties to the agreement implement a carbon price, warning that the Paris promise cannot be met otherwise.

Even without a global and harmonized carbon price system, the value of fossil fuel stocks is declining sharply. The three largest US coal producers have filed for bankruptcy, the US domestic oil and gas industry is in turmoil, and ExxonMobil’s credit rating has just been downgraded for the first time since the Great Depression. Heavyweights like Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, warn markets about stranded asset risk and the looming carbon bubble.

The fiduciary case

Today, both ethical and financial considerations are aligned and both are consistent with our fiduciary duty as charitable institutions. Philanthropy is not just any investor. We enjoy charitable tax status because of our pledge to serve the public good. Moreover, new regulations from the US Department of Treasury are explicit that mission investing is consistent with fiduciary duty. They are clear that when there is tension between values and maximizing profits, charitable organizations have significant discretion to prioritize the former. New guidance from the UK and Canada is consistent with this – in fact, more and more academic and legal weight suggests charitable institutions may actually have a fiduciary duty to divest from fossil fuels.

‘Philanthropy is not just any investor. We enjoy charitable tax status because of our pledge to serve the public good.’

Investing in climate solutions

Meanwhile, the global growth in renewable energy is defying expectations. The International Energy Agency underestimated solar’s growth over the past five years by 300 per cent. Last year, over three-quarters of new energy infrastructure in the US was renewable. A race to innovate breakthrough batteries for transportation and grid storage is under way, and will further disrupt traditional energy markets over the next decade.

Many foundations are joining the ranks of mission or impact investing, but we must do more, faster. We have unique power to accelerate the energy transition and contribute to the ‘Clean Trillion’ that must be invested annually to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. The divest-invest pledge is a straightforward way to make this contribution.

‘Two billion people today live in extreme energy poverty, standing at a crossroads between dirty and clean energy. The path chosen will have profound implications for them, and the world.’

Divest-invest – our charitable mission demands it

Two billion people today live in extreme energy poverty, standing at a crossroads between dirty and clean energy. The path chosen will have profound implications for them, and the world. If all the world’s foundations invested just 1 per cent of their portfolios in clean energy access, imagine what we could do?

In the final analysis, it is our charitable mission that most demands that we divest and invest now. Treating investments and grants as separate is a missed opportunity to put our whole portfolio to work in service to the greatest challenge of our time. It is not enough to divest in silence, as many foundations are doing now.

To stand up, to be counted, this is what the world needs now. We invite you to join the ranks of the 140 foundations and family offices recognized for brave philanthropy.

Ellen Dorsey is executive director, Wallace Global Fund. Email edorsey@wgf.org

Sian Ferguson is trust executive, Sainsbury Family Charitable Trusts. Email Sian.Ferguson@sfct.org.uk

Clara Vondrich is global director, Divest-Invest Philanthropy. Email clara@divestinvest.org

Comments (0)