The underlying message of the Sustainable Development Goals is reflected in the statement no one gets left behind. It is hoped that the SDGs move on from an agenda that is ‘done to’ developing countries towards a far more collaborative vision. They ask wealthier countries to consider how to tackle the poverty and inequality that still exists in their own societies. ‘End poverty in all its forms everywhere’ is pretty unequivocal. The scale of these aspirations is inspiring and intimidating. But that simple clear message – no one gets left behind – is a good starting point in coalescing the efforts of all those working to help people and communities improve their lives. This ought to feel like a global movement rather than another set of development targets for ‘poorer’ nations.

There’s a broad cultural point for civil society funders to consider. Firstly, how do we empower people – who might previously have been left behind – to shape and lead this agenda? Examples include the Fund for Shared Insight – an initiative of US funders that supports the sector to act on and learn from feedback from the people they aim to help.

Global Giving is one of the organizations involved – its funding platform supports and provides incentives to grassroots groups to use information to improve performance and responsiveness to the communities they serve. Better feedback loops ought only to be the start of our efforts and not the conclusion. Funders and delivery agencies need to ensure people shape, deliver, and ultimately own, developments in their communities.

It’s worth taking a look at the Young Foundation’s Amplify ethnographic approach in Northern Ireland. It uses methods ranging from kitchen chats, storytelling groups, and community walks alongside more traditional tools such as focus groups and interviews to build up shared community narratives that could guide investment in community ‘innovations’.

‘Individual funders and philanthropists will need to use their judgement around where they can add value, and who they need to collaborate with to make positive change happen.’

The underlying principle was to engage people on their terms, in their spaces. And as a result, more than 800 people contributed to decisions to invest in 24 innovative, local enterprises that could improve their community, including an upcycling retail unit, and a smart tech company helping people to manage their energy use. Are these the things that funders and philanthropists would have identified on their own?

Beyond this broad cultural point, individual funders and philanthropists will need to use their judgement around where they can add value, and who they need to collaborate with to make positive change happen.

The Big Lottery Fund’s hyper-local focus includes grants of a few hundred pounds through to multi- million pound programmes; we use grants and trusts as well as work with social investment intermediaries. We fund at country, UK, and international levels. In this context, two SDGs particularly stand out to me:

Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, sustainable . . .

The notion of investing in ‘places’ as a way to achieve impact is increasingly important both domestically and internationally. Drives toward greater political devolution in the UK mean that cities and regions will become more important in determining how power and resources are shared locally. Using a place-based lens isn’t new to us. Asset Based Community Development (ABCD) influenced the Our Place programme in Scotland, and Big Local in England. And we’ve recently launched Communities Can, an initiative to reach into areas identified as requiring support to develop the skills, knowledge and confidence of small – with a turnover of less than £10,000 – civil society organizations. This reflects a desire to fund in a way that is more responsive to local context. Internationally, the Global Fund for Community Foundations helps community funds play a key role in fostering community giving and social action that target local priorities.

The challenge in achieving this SDG is resisting the desire for a one-size-fits-all model of an inclusive, safe, resilient, sustainable ‘place’. Across all of our funding approaches, we put people and communities in the lead rather than imposing top‑down solutions.

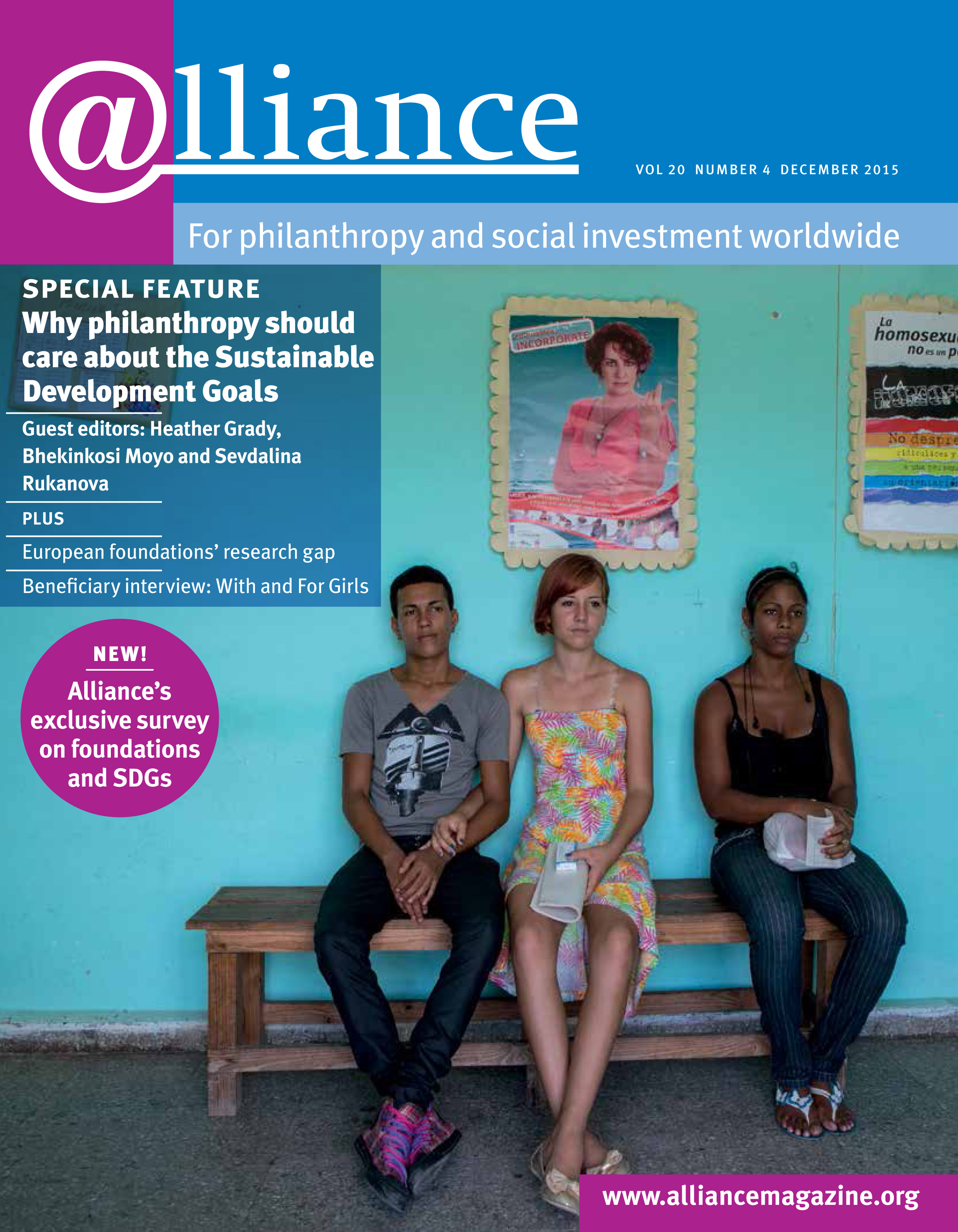

The Young Foundation’s Amplify ethnographic approach in Northern Ireland uses many methods to enhance a sense of community.

Goal 16: Promote peaceful inclusive societies with justice for all in accountable institutions . . .

We’re really interested in where ‘doing good’ will come from in future. Here in the UK, the move away from state institutions providing services to improve social conditions and a greater imperative for civil society to provide for social welfare is a key trend for UK funders – what do people and communities need to thrive in this context? And how does that determine what those ‘effective, accountable and inclusive institutions’ might look like? There’s a wide range of practice to reflect upon. How about the self-help group movement in India, mobilizing over 100 million women since the 1980s, which has now inspired a similar movement in Scotland, supported by Wevolution? Or the work of Strive in Cincinnati, bucking national trends in education outcomes by bringing diverse partners together in collective pursuit of a single set of goals? Both have created new platforms for people to get involved, to demand more from their combined resources, and to hold each other to account for what is achieved.

Our international funding has traditionally focused on using and building the assets and skills of communities, and we now want to do even more to ensure local people and institutions are at the forefront of determining priorities and delivering solutions. At the same time, we need to ensure these efforts inform and promote broader structural change to address the root causes of inequality and poverty. Our partnership with University College London on maternal and child health in rural Bangladesh and India is one example – mobilizing local women to collectively identify problems and solutions, while also working with local stakeholders and policymakers to support improved health systems, and using learning to influence national and global policy.

Testing out how best to empower communities to identify and address local priorities will be a crucial task for all of us as we work towards the SDGs and that essential principle.

Dawn Austwick is chief executive of the Big Lottery Fund. Email dawn.austwick@biglotteryfund.org.uk

Collaboration will be the watchword for SDG implementation – we’ve learned a few lessons:

What can you achieve when you don’t care who gets the credit? The social challenges of the day are too complex to address alone. Rather than ‘slice and dice’ problems into manageable solutions that demonstrate ‘our’ individual impact, funders should seek out more ambitious collaboration with all the players involved in really tackling an issue.

Money talks, but it needs to listen more. Funders are in a privileged position by virtue of the resources we have. But we need to understand our specific role within a wider ecology of people involved in making social change happen, rather than trying to direct that change ourselves. Are we bringing the right people together? Are we doing enough to support people and communities to take a lead on how they improve their lives?

Ask ‘what matters to you?’ not ‘what’s the matter with you?’ Aspirations like ‘ending poverty’ run the risk of focusing our minds too much on what people don’t have. Initiatives like GiveDirectly show how what we might have previously regarded as the most ‘impoverished’ people in the world have skills, ideas and energy that can be unlocked with a little support.

Main image: Credit Newfrontiers.

For more discussion on the SDG debate, listen to our Alliance Audio podcast.

Comments (0)