Despite the fact that 40 per cent of the 116 environmental activists murdered in 2014 were indigenous[1] and a significant portion of the oil, gas and mining production (39 per cent now and 46 per cent of future reserves) is on or near indigenous land[2] — the Paris Agreement removed all references to indigenous rights from the binding portion of the agreement. Indigenous rights were relegated to the preamble, where they serve as an aspiration rather than a commitment. Why are indigenous peoples systematically eliminated from the climate debate?

One reason is because climate change is addressed almost exclusively through a western science-based lens and approach; yet volumes of scientific literature recognize the efficacy of traditional ecological knowledge and land stewardship practices in protecting the environment and biodiversity. Legally owning 11 per cent of forests and inhabiting 22–24 per cent of the earth’s land surface,[3] indigenous livelihoods are typically low-carbon or carbon-neutral, and contribute the least to global warming. Simply put, it is not a coincidence that 80 per cent of the world’s remaining biodiversity is to be found on indigenous lands. So why aren’t the climate scientists collaborating with indigenous peoples (IPs) on a global framework for preventing, mitigating and adapting to climate change that includes traditional ecological knowledge?

‘It is not a coincidence that 80 per cent of the world’s remaining biodiversity is to be found on indigenous lands.’

Support for IPs to work on climate change is virtually non-existent. Less than one tenth of a percent of the hundreds of millions of aid and philanthropic dollars going to prevent, mitigate and adapt to climate change goes directly to IPs. Of the funding going to indigenous organizations, the majority comes from government agencies within the European Union, which have official policies for working with IPs.

‘Less than one tenth of a percent of the hundreds of millions of aid and philanthropic dollars going to prevent, mitigate and adapt to climate change goes directly to IPs.’

European support for IPs has been effective in three major ways: Europeans stress process over discrete one-off projects; support is long-term and continuous over decades; and rather than imposing their own priorities or agenda, most European support responds to the needs of indigenous communities. The US counterpart – the Agency for International Development – has no policy for IPs, and lacks the interest shown by the Europeans, leaving philanthropy as the greatest source of support. Yet the efforts of US foundations tend to be uneven; funds are to implement the donor’s agenda, and grants tend to be routed through other NGOs and intermediaries. Why isn’t philanthropy doing more?

‘The philanthropic community attributes such a low level of funding to the lack of IP capacity, but often the philanthropic lens limits the donors’ capacity to adapt their paradigms to the worldviews of IPs.’

The philanthropic community attributes such a low level of funding to the lack of IP capacity, but often the philanthropic lens limits the donors’ capacity to adapt their paradigms to the worldviews of IPs. Donor bureaucracy fails to adapt funding models in ways that allow IPs to define their own development destinies according to their own understandings of success. It is true that many indigenous organizations have difficulty with the application, budgetary and reporting forms of different donors. It is equally true that one of the most profound successes of the 21st century is the global adoption of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, clearly evidence of a sophisticated range of IP capacity.

So why should foundations increase support to IPs? A 2008 World Bank study of 140 successful climate change strategies found that 100 per cent were implemented by local community organizations. Not a single successful solution was found within governments or the private sector. The report concluded that the typical big institutional approach to climate change was counterproductive to the kind of innovation, creativity and practice found in all the successful solutions for mitigating and adapting to climate change. What is needed from philanthropy is a ‘bottom-up’ financing system that provides flexible, agile and incremental funding, and links local organizations with partners at the national, regional and international levels.

Rebecca Adamson is founder and president of First Peoples Worldwide. Email radamson@firstpeoples.org

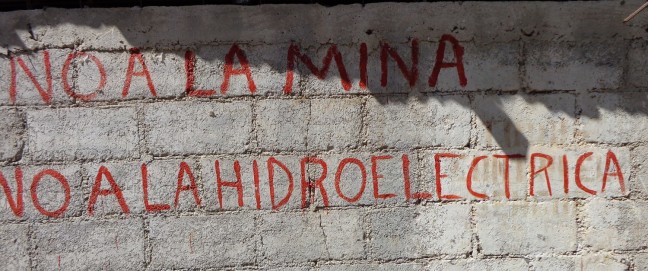

Lead image: Wives at a hearing for their husbands in October 2015. All three husbands were political prisoners related to the hydroelectric dam, Hidro Santa Cruz in Santa Cruz Barillas, Huehuetenango, Guatemala.

Comments (0)