Why are the worlds of philanthropy and the media still so far apart? What could and should be done to bring them together and realize the promise of a reciprocal relationship?

In this special feature, we look at the space where these two worlds collide, and what happens as a result. I argue that now, more than ever, philanthropy and the media don’t just need to work more effectively together, they actually need each other to fulfil their respective missions.

Philanthropy and the media are well defined terms. Philanthropy is roughly the promotion of the welfare of others using money towards causes in the public interest. The media refers to the main means of communicating to audiences, in this case, principally the transmission of news and information.

Yet today, the definition of both philanthropy and media are being stretched.

For example, is the purchase of The Washington Post by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos an exercise in philanthropy?

For most people, it would be a clear no. However, it did save the publication from vanishing. Is the acquisition of a dominating stake in The Atlantic by Laurene Powell Jobs and her company, the Emerson Collective, an act of philanthropy? They argue it is.

Meanwhile, journalism today has many different faces and is delivered by many different types of organizations. Consider constructive journalism, as defined by Ulrik Haagerup at The Constructive Institute and solutions-oriented journalism by Tina Rosenberg and David Bornstein in their NYT column Fixes; consider journalism as a public and community service as defined by Jeff Jarvis and others at the City University of New York. News provision and storytelling is now, as much as ever before, committed to the betterment of the audiences it serves.

But this is not new. Ralph Waldo Emerson, a co-founder of The Atlantic 160 years ago, established the mission of the organization as to ‘bring about equality for all people’, an ideal cited by Powell Jobs in her acquisition of The Atlantic.

But the context has changed.

Political and social events happening across the world over the last two years have shaken our world. As Bruce Sievers and Patrice Schneider argue, ‘civil society’s information base, its norms and its operating mechanisms’ are under attack, presenting ‘an existential threat to democracy’.

If we had produced this special feature two years ago, the arguments would be different: consider today what both journalism and philanthropy need to contend with: hundreds of websites routinely spread misinformation and automated accounts known as ‘social bots’ are being programmed to spread fake news.

Political processes have been damaged such as the peace accord referendum in Colombia, and elections in the Netherlands, France, and the US.

Meanwhile, media manipulation is contributing to the shrinking of Eastern Europe’s democratic space, the fomenting of the far right in Germany, as well as fuelling conflict in Syria, Yemen, Myanmar, Turkey, and shocks such as Brexit or the constitutional crisis in Spain.

All of these events are heavily influenced by cyber-politics operating in real time, with real-time analytics, including social listening – the process of monitoring digital conversations to understand what individuals are saying about a topic.

Regrettably, neither philanthropy nor the media have been ready or able to combat these sophisticated tools. At least, not yet.

Why did we not see it coming and prepare more for it? Should the priorities of philanthropists and their foundations, and the public conversation and discourse shaped by the media, have changed more quickly in response to major shifts in the political landscape?

Philanthropy is reacting… slowly

In the US for example, the prototype fund run by the Knight Foundation, the News Integrity Initiative, funded by Facebook and run by CUNY, is reinvigorating a taste for media literacy and giving new impetus to fact-checking initiatives. As illustrated in our profiles, a handful of US-based philanthropies are trying to mitigate the effects of disinformation and propaganda.

In Europe, a response has come from European institutions and some governments, notably Germany. Some foundation programmes are already in operation, with European foundations such as ZEIT Stiftung and Fritt Ord making important contributions. Other promising initiatives such as the Fund for Democracy and Solidarity in Europe have been announced but are yet to be fully operational.

In truth, this latest political upheaval across the world has brought to light not just how unprepared philanthropies were, how reactive, how little we knew about these possible scenarios. But journalism was also taken by surprise. We, philanthropies, we, the journalists, weren’t curious enough.

The current media environment is not good news for anyone in civil society, and that includes philanthropy. The information base of democracy, its norms and its operating mechanisms are ‘threatened by a storm that takes everything on its path’, as Sievers and Schneider describe.

What should philanthropy do?

As James Deane highlights, philanthropy has come to the ‘sudden recognition of just how much independent media mattered and just how weakened democracies had become by misinformation and disinformation’.

Philanthropic funding of media needs to address what Sievers and Schneider consider fundamental to overcoming the most immediate threat today, ‘the decline of civic media and the resulting deterioration of public discourse’ as a prerequisite for a functioning civil society.

Philanthropy has made possible numerous independent news providers in places where the flow of information is challenging, like MalaysiaKini in Malaysia, most non-for-profit investigative reporting around the world, such as IDL-Reporteros in Peru, and even the organizations behind the coordination of the Panama Papers investigation, among many others. These are some of institutional philanthropy’s most significant contributions.

However, philanthropies are pushed and push themselves in many directions. There are many urgent social needs, beyond confronting failing trust and growing misinformation. For example, foundations play important roles in funding media to maintain and deepen coverage of particular causes such as climate change, resilience and urbanization, global health, and humanitarian assistance, among many others.

But foundations need to develop more cohesive funding strategies. As James Deane notes, philanthropies have ‘different, sometimes competing philosophies, world views, results frameworks and an unusual degree of faddism and inconsistency’.

This is a fair charge: philanthropy has not organized itself with the coherence and at the pace it needs to confront the big problems noted above. Numerous efforts have been made, but are still a work in progress.

These include leading philanthropies organized around different affinity groups focusing on a particular cause or geography, for example, or initiatives such as Media Impact Funders in the US and the Journalism Funders Forum in Europe.

In media, the story is the commodity and trust is the currency

If philanthropy is, at its best, at the forefront of the quest for social justice, then media is, at its best, at the forefront of halting the biggest abuses. At a minimum, it is capable of defining conversations and setting the agenda.

Columbia University’s Anya Schiffrin articulates better than anyone that ‘journalists have been calling attention to some of the same problems for more than a hundred years’. Their writing had significant impact and a wave of ‘committed and campaigning journalism’ always existed in moments where a ‘general climate of intellectual ferment and political activism’ called for it.

Yet, the media has gone through a massive transformation over the last decade, impacted by three distinct trends. First, the technological revolution has made us question most of our assumptions about what a media system looks like, how it is created, what it does, and to what effect. On top of that, a potentially even bigger wave of disruption – anchored in artificial intelligence, robotics, cognitive computing, and big data – is under way.

The most noticeable casualty of this transformation is the funding model. Many in the industry were left feeling that they have no option but to resort to ‘clickbait’ to pursue advertising money, but advertising money wasn’t always there.

The impact of artificial intelligence, robotics, cognitive computing, and big data is likely to bring a potentially even bigger wave of disruption. credit Ars Electronica

Second, and more importantly, the media industry lost its ‘north star’ in pursuit of its own survival.

The reality it faced meant that survival of the industry took precedence over the mission of the industry to provide a service to society.

‘There is no such thing as the news industry anymore’, laments Emily Bell in a report on Post-Industrial Journalism published by the Tow Centre for Digital Journalism at Columbia University.

While this may be over-stating the decline, there is widespread agreement that a continuous disruption of the media industry has resulted in a market failure for public interest journalism and specifically news and information on the issues that were underreported at the best of times, and rarely covered regularly or in-depth.

The third crisis faced by the media is a decline of its credibility. A 2017 survey for the Reuters Institute’s Digital News Project showed that trust in media in the UK fell by 7 per cent compared to 2016. Meanwhile, Edelman’s annual report on trust found declines in public trust in the institutions of government, business, media and NGOs around the world, with the greatest drop for media.

But not everyone is pessimistic. Barbara Hans, for example, writes about a real opportunity for media to ‘return to its true function in society and its vital role in democracy’.

What is behind this optimistic view? While media may be reeling, what is not dying is the authority and influence it exerts. Many agree that news media still matters in setting the agenda. It signals what is important to the public and what the public should be paying attention to, and is a mechanism that policymakers feel they need to respond to in order to retain legitimacy.

Time to pay more attention to audiences and impact

A few years back the mere notion of tracking impact made both philanthropies and media uneasy. Today, both are much more comfortable trying to figure out what works and what doesn’t.

In fact, the more interesting work in this area comes from the media itself. While for philanthropy, there is a responsibility to make the most efficient and effective use of every philanthropic dollar, for media, its survival may depend on its ability to understand if it is informing and engaging a growing audience, or effecting any change in the real world.

Measuring audience response to a journalistic story by means of counting page views and unique visitors is necessary but not sufficient. For example, Anjanette Delgado, digital director and head of audience for largest US news publisher Gannett’s lohud.com and poughkeepsiejournal.com, has shown how they wanted to know more at her Gannett newspaper in Westchester County: ‘What happened when we started asking questions about a story? After we published a story? When a key decisionmaker or a crowd of people saw that story? Did we spark a change in law, a donation, a citation or the dismissal of an unlawful employee? Did the family who lost their father’s Purple Heart years ago finally find it, with help from the crowd? Did we make a difference?’

These questions of impact are at the core of the role that journalism ought to be playing. For parents in Texas who are worried about the best school choice for their children, The Texas Tribune has developed a search engine that allows them to explore and compare Texas’s state districts and public schools.

In Kenya, thanks to the vision of The Star editor and the work of Code for Africa, the media now offers its audiences an opportunity to check if their doctors are as qualified as they claim.

Journalism matters, but the question that philanthropy asks is, what journalism matters most? As media consumers we have access to more and better content that we can ever digest in many lifetimes; the problem media faces is how to inform, engage, target, and influence the right audiences.

The media needs a transformational purpose. Parallel to the crises of media, but completely related, the media still needs to repurpose itself, a service, to become news that can be used.

Journalism now comes in many different shapes, but also new models emerge, such as The Conversation – ‘providing reliable information, working with academics and researchers, based on the premise that just as clean water is vital for health, clean information is essential for a healthy democracy’ – investigative newsroom ProPublica, and mega collaboration projects such as the International Consortium of Investigative Journalism, among many other variations. However, the goals remain the same: to positively affect the societies they serve.

‘Committed and campaigning journalism’ is now part of everyone’s media diet and most times indistinguishable from more traditional definitions of journalism. Building public support for causes is in the DNA of The Guardian, while producing journalism that ‘spurs real-world impact’ is core to the mission of ProPublica.

Philanthropy is not the answer to sustainability

The trap would be to believe that philanthropy is the answer to sustainability. It is not and it must not be. As journalist Gustavo Gorriti notes, ‘there is a great disparity between the consensus on the importance of free, investigative journalism for the health of democracy and the very small percentage of philanthropy allotted to support it’.

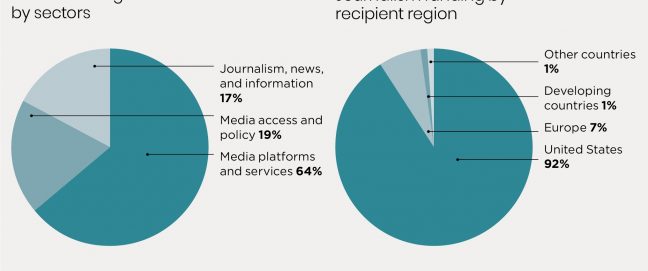

If we look at the size and distribution of global philanthropy, we can easily conclude that the disparity exists.

Venture capital doesn’t invest in media either – less than 7 per cent of all venture capital in Africa goes to support the media, and the funding and geographic expansion of newcomers like BuzzFeed, Vox, Upworthy, and Business Insider has significantly slowed. Entire sectors of philanthropy, such as social investment and impact investment, don’t yet have it on their radar, with a few notable exceptions.

Concluding thoughts

This special feature aims to highlight structural concerns in the relationships between the media and philanthropy.

The philanthropy practitioners who read Alliance will encounter some challenging observations: from Gustavo Gorriti, someone who has received significant philanthropic support over the years, that ‘there is nowadays a measure of enlightened despotism in our relationship with foundations…’ From Tom Rosentiel and Kevin Locker who set out ethical guidelines ‘… adhering to editorial independence, transparency and clear communication articulating their reason for funding journalism’ and Barbara Hans on the opportunities and the boundaries of cooperation.

Like many others, we at the Gates Foundation adhere to guiding principles in our media funding: transparency, respect for the editorial and creative independence of grantees, and mutual respect for the editorial integrity of the content. This means that stories are covered based on editorial merit, and must be evidence-based and of value to the audiences they affect.

However, this special feature also hopes to point to what needs to happen to better work together in solving societies’ problems: seeking alliances to reach goals, achieve missions and fulfil shared commitments. There are challenges for all of us.

Media needs to welcome change, embrace its obligations and help in delivering social change. It needs to do a better job at demonstrating value, evidencing why media matters.

When working with philanthropies, there must be mission alignment, not just an added revenue model, otherwise the partnership model doesn’t work.

For its part, philanthropy needs to step up and understand that first, without functioning media, civil society collapses; secondly, our aspirational goals can be achieved better by working with the media.

Most of all, we need to remind ourselves of the many moments when journalism really mattered. Re-reading Global Muckraking: 100 years of investigative reporting from around the world or Democracy’s Detectives: the economics of investigative journalism would be a great start.

Media and philanthropy must respond to the challenges we face. Now is a critical time.

A spirit of enquiry isn’t an option – it’s a necessity.

Miguel Castro is senior officer, global media partnerships, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Email miguel.castro@gatesfoundation.org

Comments (1)

Indeed, the need of the hour: Media and philanthropy must respond to the challenges we face. Now is a critical time.