Feminism’s purpose is to disrupt power and funders who support it need to embrace this principle to achieve genuine gender justice

Feminism is about disrupting power, so feminist philanthropy is about challenging and disrupting the power of resources and the power dynamics between those who give the resources for gender justice and those who claim them.

From 25-27 September 2019, 150 women’s, girls’ and trans activists from across Asia and the Pacific and beyond met in Bangkok to unravel the complex reality of feminist funding in the region. Organised by eight women’s funds members of the Asia and the Pacific chapter of Prospera, the International Network of Women’s Funds, the convergence brought together grantee partners, regional allies and funders to talk about power, resources and the processes through which they are negotiated.

Organising around women’s and trans persons’ human rights often flies in the face of tradition.

Money represents power, particularly in Asia and the Pacific where resources for social justice work have come from either government sources or the West. The prevailing philanthropic culture has largely been focused on religion or charitable causes, and organising around women’s and trans persons’ human rights often flies in the face of tradition.

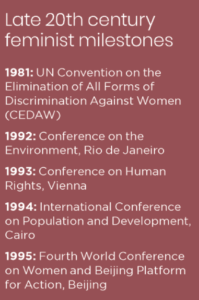

The era of the conferences

This has begun to change, in no small part initiated by a series of landmark conventions and international conferences in the 1980s and 1990s. Prior to these events, the focus of both bilateral and foundation giving in the Global South was on ‘development/empowerment’ models. It was the feminist rallying call that ‘women’s rights are human rights’ in 1992 at the World Conference on Human Rights held in Vienna that reframed and moved the discourse to a rights-based approach.

Those resources needed to go towards unpacking the socio-political relational dynamic that has produced inequality, discrimination and violence.

The era of the conferences also saw the emergence of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, in 1981; pushed through by the efforts of women coming together from across the world. National and regional preparations for the conferences were dynamic spaces for taking the feminist analysis of power and resources further. They led to more conscious support for women’s issues, with an effort to include their voices when designing the initiatives. Leading up to the Fourth World Conference on Women, which produced the Beijing Platform for Action, many global commitments gave rise to national machinery and public institutions for pursuing women’s rights. And for a decade following the Beijing conference, efforts were undertaken to ensure increased feminist understanding of development and of women’s role in it.

Gender mainstreaming has come at a cost

However, in the last 15 years, despite resources continuing to be committed to gender equality, its framing has come from a gender-mainstreaming approach. In the interventions which have followed, feminist leadership has been the greatest casualty. This has led to an absence of sustained and engaged feminist design or even analysis of the programmes with the goal of equality and non-discrimination. The result, for philanthropic giving and international aid, has been that the power of resources has not shifted to those who are claiming them. They have remained mere recipients.

While a significant rationale for the creation of women’s funds was lack of resources, it was also informed by a concern for the ownership of these resources. Simply earmarking resources to address violence against women or support ‘women and girls’ was not enough. Those resources needed to go towards unpacking the socio-political relational dynamic that has produced inequality, discrimination and violence, and be put in the hands of those who have lived those realities. In addition, to be integral to the movements built to challenge and eliminate them, their leadership must be recognised and respected.

The first women’s fund in our region, Tewa, was set up in Nepal in 1995, with the goal of unlocking local philanthropy for women. The Korean Women’s Fund (now known as the Korean Foundation for Women), was set up in 1999 to ensure gender equality, by supporting women’s movements and women’s empowerment. MONES, the Mongolian Women’s Fund, was created in 2001 to provide financial support to women’s groups as well as marginalised women in abusive situations. HER Fund in Hong Kong followed suit in 2004, with the aim of educating givers to fund causes that were about human rights and supporting women. The South Asia Women’s Fund (now Women’s Fund Asia) was also created in 2004 as the first sub-regional women’s fund to work as a catalyst for local giving to women’s rights work in the region. More recently, the region has seen the emergence of South Asia Women’s Foundation of India, closely followed by Urgent Action Fund-Asia and the Pacific, and the Fiji Women’s Fund; the latter two linking the political voices of Asia and the Pacific.

At Women’s Fund Asia (WFA), our model of feminist philanthropy recognises the value of small budget organisations and even unregistered groups at the grassroots who build and sustain gender justice movements. It ensures that the resources unlock the potential of the work and do not become a burden. We make sure that we remain accountable to the movements through the way in which we build and implement our strategies. It is because of our power analysis that the women’s funds are clear that they do not implement programmes. They mobilise resources, they influence resources in a way to make sure that women and trans-led groups are able to control the use of the resources for the strengthening of their movements.

Including trans people in feminist grantmaking

A core value of women’s funds is to listen very carefully and then act on the message. WFA, one of two regional funds in Asia, realised that it was not receiving applications from groups led by trans people, unless they were in partnership with others. In its regional convergence in 2017, therefore, it sought to understand why. It was taken aback to learn that the groups did not think they were eligible, given the emphasis on the term ‘women’.

WFA’s team and Board of Directors reviewed the vision and mission, and the statements were redrafted to ensure that support for and work with trans communities were made explicit.

Accountability, a central tool of dismantling power, was amply demonstrated in Bangkok, as the women’s funds responded to hard questions raised by their partners and allies, from articulating what feminist funding is, to the difference between networks and women’s funds; and even more importantly, clarifying the role of women’s funds themselves, and their relationship to the movements they support.

Accountability, a central tool of dismantling power, was amply demonstrated in Bangkok, as the women’s funds responded to hard questions raised by their partners and allies, from articulating what feminist funding is, to the difference between networks and women’s funds; and even more importantly, clarifying the role of women’s funds themselves, and their relationship to the movements they support.

The feminist philanthropy movement in Asia and the Pacific, in addition to mobilising resources that are guided by feminist principles, engages with resources politically, disrupting power relations of those that give and those that claim, as well as ensuring that the mystery of resource control is made transparent and visible.

As funders, we ask for a political analysis of the control of resources that examines growth, depth of reach and impact; rather than an application of a simplistic ‘efficiency’ model, which bases it grants on size and management.

As we step forward to be held accountable to the movements we support, we call for a more substantive engagement with resources, rather than an adversarial one. Let us be accountable and transparent about ways in which we access and use resources as part of a larger collective; and strengthen the feminist movement for resourcing human rights.

The author wishes to thank Claudia Bollwinkel and Alexandra Garita and all the co-thinkers in WFA for their invaluable contributions to this article.

Tulika Srivastava is executive director of Women’s Fund Asia.

Email: tulika@wf-asia.org

Twitter: @WF_Asia

Comments (0)