A major new survey reflects concerns that philanthropy doesn’t give enough support to peace-building activities. If only it would, its qualifications for doing so are striking

This article gives early results from a survey called ‘Philanthropy for a safe, healthy and just world’. Conducted by Centris and Candid and supported by Peace Nexus, the survey examines issues such as the extent of support for peace-building, the characteristics of peace-building organisations compared with others, and why some organisations engage with peace while others don’t. Findings are based on 823 responses to an open survey conducted between February and March 2019.

Why the survey was done

The premise for the study was that peace is under-represented in philanthropic funding. Groups such as Foundations for Peace have been trying to raise the importance of peace-building for more than a decade, yet have been largely ignored. The findings reported here suggest that such informal observations are supported by hard data.

Our starting point was the Peace and Security Funding Index developed by Candid and the Peace and Security Funders Group. In 2016, this identified 2,605 peace and security grants totalling $328 million from foundations globally. However, only $11.6 million of this – or 3.5 per cent – was specifically for peace-building. This sum is tiny when compared with the $32 billion given by the largest 1,000 US foundations in Candid’s 2016 research set.

Peace-building organisations typically pursued matters of economic equity, displaying a desire to reduce social marginalisation, while pursuing democratic participation and community organising.

Similarly, in The State of Global Giving by US Foundations, a five-year trend analysis (2011-2015) of international grantmaking by 1,000 foundations, peace and security funding accounted for 0.8 per cent of the total.

Given the lost lives and social and economic opportunities, and damage to property associated with conflicts, this is surprising. Why is this area of work underfunded? Is it because foundations are more risk-averse than they like to believe? Is it because they don’t see the connection with peace-building and other everyday basic societal needs? These are some of the questions we try to answer, though the overall goal is to stimulate discussion by examining the broad contours of the field. This article is just the start and the results produced here, which are a small fraction of a much larger data set, will enable the field to engage with the role of philanthropy in producing a safe, healthy and just world. Three-fifths of the respondents to the survey said that they were keen to discuss this.

As a frame for the study, the questionnaire looked at the wider role of philanthropy in social change, delving into the policies and practices of organisations. Such an approach was designed to see how peace-building fits alongside other strategies (for example, advancing human rights or community organising).

Peace as a priority

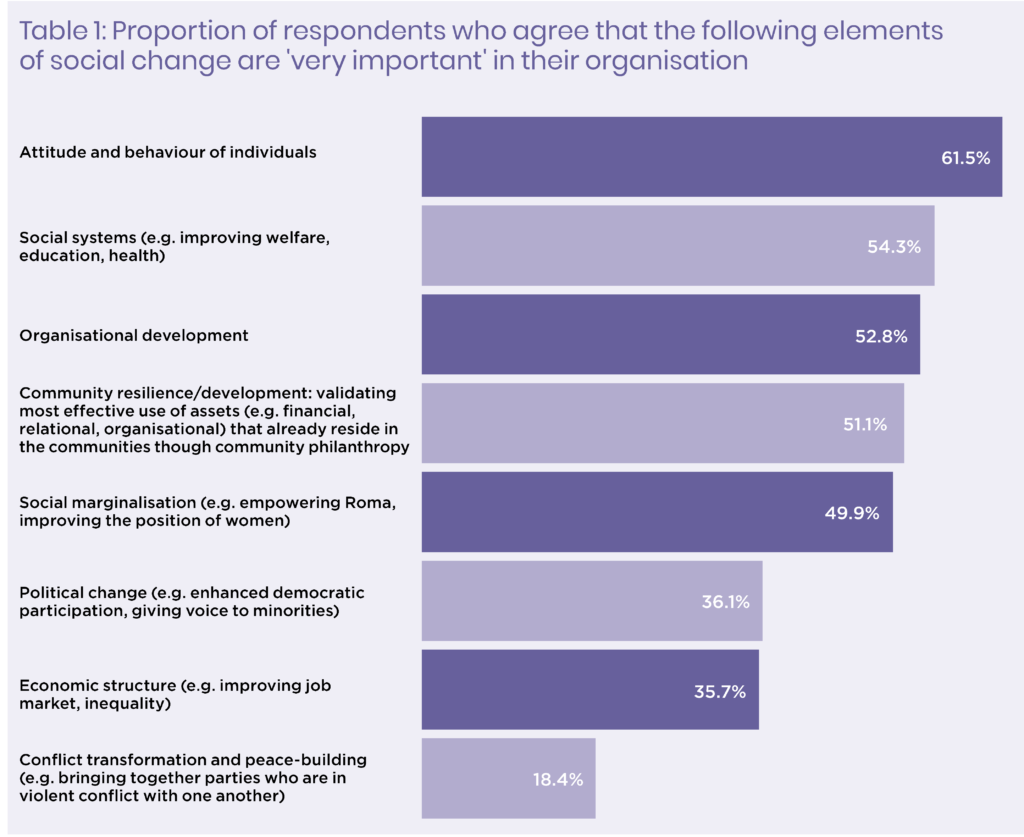

We assessed the strength of peace-building as a priority for each organisation by asking them to rate how important several different elements of social change were to their work. Answers were rated on a five-point scale from ‘very important’ to ‘very unimportant’. The proportion giving the answer ‘very important’ is shown in Table 1.

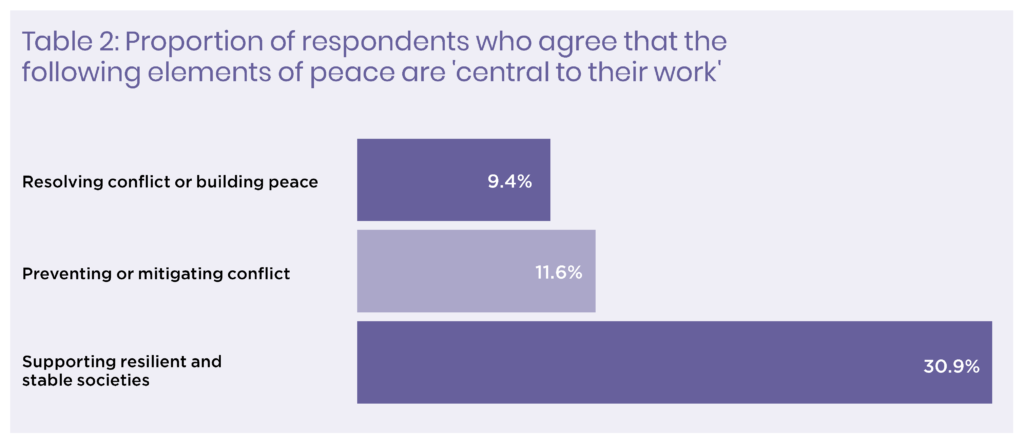

As we can see, peace-building is bottom of the list. Turning now to the question of commitment to different aspects of work on peace, respondents were asked to say the extent to which the three key elements of the Peace and Security Funders Index – resolving conflict and building peace, preventing and mitigating conflict, and supporting resilient and stable societies – were important in their work. Response options were: (a) central to our work, (b) important but not central, (c) some involvement, or (d) no involvement. The proportion of those ‘centrally involved’ is shown above.

Table 2 shows that only around one in ten are directly involved in peace-building. A slightly larger minority – around three in ten respondents – are involved in more indirect forms of peace-building.

Despite these differences, we found that responses to each of the three questions could be correlated, so that a positive rating on one question predicted a positive answer on the others. Using a statistical technique known as factor analysis, we could then construct an index of peace-building giving a score to each respondent according to how committed they were to the issue. We now use this index to compare with other questions in the survey.

Characteristics of peace-building organisations

We identified four main characteristics that tended to distinguish organisations with high scores on peace-building from the rest.

First, those organisations scoring highly on peace-building also scored highly on factors associated with the pursuit of social justice and human rights. Peace-building organisations typically pursued matters of economic equity, displaying a desire to reduce social marginalisation, while pursuing democratic participation and community organising. They were more likely to be involved in political advocacy, protection of the rule of law and equal access to services. They were more likely than other organisations to pursue a partnership approach engaging with many organisations of different types.

Second, peace-building organisations were more likely than other kinds of organisation to be working in an area that has recently been affected by war or violent conflict. Just under a third of respondents said that they were working in such areas and, of those, 46.5 per cent were in the top quartile on the peace-building scale. Of those working outside those areas, only 14.8 per cent were in top quartile on the peace-building scale.

The most committed peace-building agents are NGOs/civil society organisations and the main donors are individuals. Endowed foundations are among the least committed.

The third factor was size. There was a statistically significant correlation between number of staff and a high score on the peace-building scale, with larger organisations being more likely to be involved in peace-building activities.

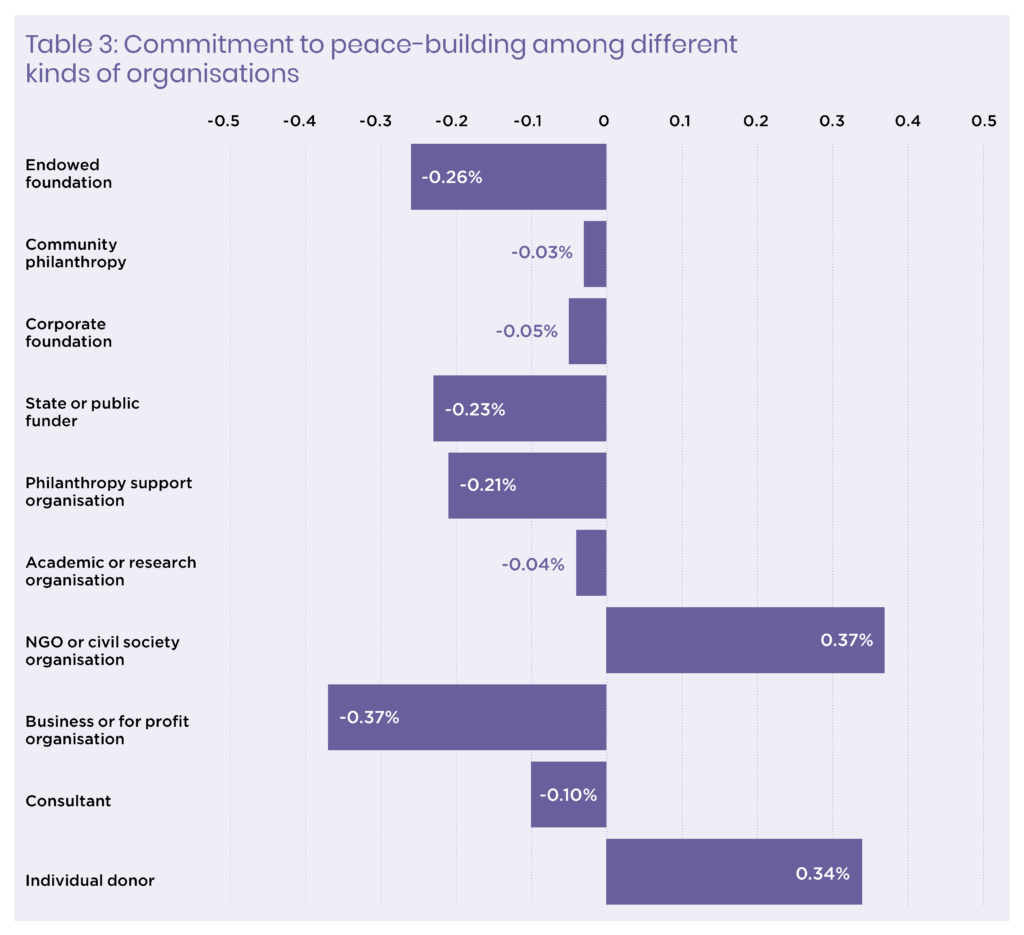

The fourth factor was type of organisation. Since the survey was open, many different types of organisation responded. Table 3 sets out mean scores on the peace-building scale according to organisation type.

Note: The peace-building scale here uses mean z-score for each group. The z-score is the number of standard deviations from the mean data point and can be negative (low commitment to peace-building) or positive (high commitment).

Table 3 suggests one probable cause for the shortage of funds for peace-building, noted earlier. The most committed peace-building agents are NGOs/civil society organisations and the main donors are individuals. Endowed foundations are among the least committed.

Reasons for and against engaging in peace

The survey probed why some organisations engage in peace-building while others do not. Organisations cited four main reasons for becoming involved. The most common, cited by 94 per cent of respondents, was that they were committed to dealing with the root problems in a society and conflicts were often found there. Without a stable basis in society, other development issues could not take hold. A further reason, cited by 80 per cent, was a commitment to a specific country and violent conflict happened to be part of what was going on. Background reasons included the alignment of peace-building with the core values of the organisation and the experience of its trustees or founders.

Philanthropy appears to have a unique role to play in conflict because it possesses three essential qualities – a moral compass, financial resources and patience.

Reasons for not engaging were harder to fathom. A very common position was that they had ‘other priorities’, a statement which describes – rather than explains – their position. When probed more deeply, the main reason (given by 43 per cent) was that peace-building ‘is too political’. Other reasons included ‘it is difficult to measure progress’ (24 per cent), ‘it is not clear what works’ (24 per cent) and ‘peace-building should be the preserve of official donors’ (18 per cent). Many said that they were ‘too small’ or had ‘too few of the right skills’ or ‘conflict is not a problem where we work’. Some organisations said that they would like to engage but did not know how.

What is the potential for philanthropy and peace?

While it is evident that the involvement of philanthropy in peace-building is low, there is potential for it to play a major role.

One way of promoting this might be to encourage people to learn from some of the work that people are doing. The survey has uncovered numerous examples of success stories which, in some cases, have resulted in the transformation of communities by correcting imbalances of power. Scattered examples include the involvement of women in the Colombian peace process; the formation of local peace committees in Syria; the development of cross-community plans in Bosnia and Herzegovina; and the enabling of Muslims and Dalits to live peacefully in parts of India. Among many tangible achievements were support for a Nobel Peace Prize winner and the building of a centre for conflict studies in the United States.

Philanthropy appears to have a unique role to play in conflict because it possesses three essential qualities – a moral compass, financial resources and patience. As one respondent to the survey put it, these qualities mean philanthropy is well-placed to ‘create space for discourse on difficult and controversial issues, supporting and advocating for more support for marginalised and discriminated-against groups, particularly in the context of conflict to enable them to participate in post-war reconstruction and transitional justice issues’.

Peace and conflict go to the heart or our world. Failure to deal with conflict can result in ruined lives and lost opportunities, as well as death and destruction. At a time when philanthropy is under attack from many sides, it may be time to put aside its aversion to risk and to engage in the issue that threatens us all.

Barry Knight is secretary of CENTRIS.

Email barryknight@cranehouse.eu

Twitter @barryjameknight

Lauren Bradford is senior director of Global Projects and Partnerships, Candid.

Email lauren.bradford@candid.org

Twitter @laurenjbradford

Comments (0)