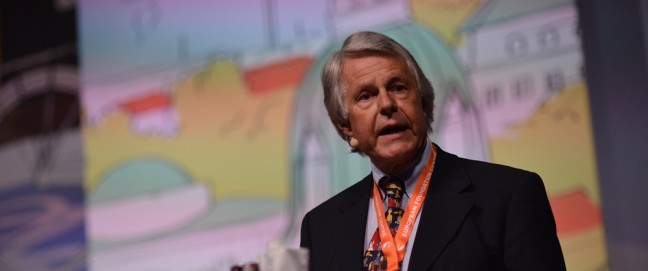

What is it like to come into a foundation which, since its inception, has had a strong and continuous family involvement in its running? How important are family values to a family foundation? And how far do specific beliefs – in this case the foundation’s Catholic roots – either inform or interfere with a foundation’s work? Peter Laugharn, new president and CEO of the Hilton Foundation, talks to Charles Keidan.

The Hilton Foundation was founded in 1944 to ‘relieve suffering’ by Conrad Hilton, who established the Hilton hotels. What were the key drivers in setting up the foundation?

Conrad Hilton was a self-made man who grew up with modest means in what was then New Mexico. He had a strong work ethic but he was also a devout Catholic who prayed before every business deal. He combined strong entrepreneurial skills, moral convictions and great compassion – all grounded in his faith. The Hilton Foundation is not a faith-based organization, but two of our 11 programmes are focused on Catholic education and Catholic sisters. Historically, we have channelled Conrad Hilton’s values and I will continue to do so, because they’re very energizing for an organization and a strong basis for philanthropic activity.

‘Historically, we have channelled Conrad Hilton’s values and I will continue to do so, because they’re very energizing for an organization and a strong basis for philanthropic activity.’

Do you think foundations that have their origins in family wealth have values particular to them?

I wouldn’t say that necessarily. This is my third family-oriented philanthropic leadership role. The first was at the Bernard van Leer Foundation, where the family had passed, but their values were still very present in terms of grantmaking. The second was at the Firelight Foundation, which was started by a couple who didn’t want the organization to be considered a family foundation, but their values were very important in the direction that it took. That’s also true with the Hilton Foundation.

Foundations where the founder was an entrepreneur are energized by their business acumen. One of the things that Conrad Hilton would always say is ‘Think big, act big, dream big’. He also said ‘Assume your full share of responsibility in the world.’ Those are good as value orientations for our work, and great for the internal culture of the foundation.

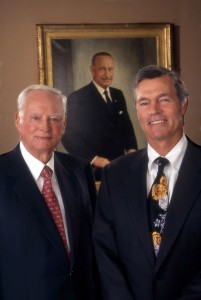

Steven Hilton, Conrad’s grandson and my immediate predecessor, is very much steeped in the values of his grandfather. In the city of Los Angeles, he is recognized as a leader in the fight to end homelessness.

In his comments about the succession, Steven Hilton wrote about the need for someone with both intellect and heart, and he described you as possessing those qualities. Has that made this transition possible?

I think it’s made it smooth. I can’t speak about the motivations of the people who hired me – you’d have to talk to them – but I know they were looking for someone who would carry on the family values; someone who would work well with the family and help them move the foundation to the next level.

Your last job was at the Firelight Foundation, which is a Hilton Foundation grantee. Does your experience as both grantee and donor prepare you well for what is a very significant challenge?

I think it’s an unusual situation in philanthropy, but I think it really helps. I can see things from a grantee perspective and a funder’s perspective.

How do you plan to overcome the often cited issue of the differential in power between the two sides?

As a fund-seeker, I would say either don’t accept a power differential or get over it! This is a partnership and the fund-seeker needs to frame it as such and prove its value. On the other hand, if grantmaking foundations didn’t have the NGO community, they wouldn’t be able to enact their missions. So I think a large part comes from the foundation being humble and constructive, but another part comes from the NGO fully taking on its role of equal partner.

An international perspective is central to your own background and experiences. Can you say a little about the work that you hope to do at the Hilton Foundation, maybe starting with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

It’s nice to work at a foundation that is both global and local in scope. As with the Bernard van Leer Foundation, there is a fruitful interplay between being grounded in your own community and being open to the world. We have 11 priority areas. We have six strategic initiatives, spending approximately $10 million a year on each. Then we have five major initiatives, which we spend $4 million or $5 million on. Our international work involves water in West Africa and children affected by AIDs in eastern and southern Africa; and the domestic focuses on ending chronic homelessness in Los Angeles County, helping foster youth, and preventing substance use; and the Catholic sisters programme is both domestic and global.

Dorothy Edwards in front of her apartment. Dorothy was homeless in Pasadena for eight years before being placed in permanent supportive housing by foundation grantee Housing Works.

How do you balance your involvement in all those programmes with the growing imperative in philanthropy to be effective and focused?

I feel that all the programmes are robust, making important changes in their fields. It is a lot of balls to juggle, and our board and staff will consider how the different programmes dovetail. For example, the three domestic programmes are all quite interconnected. There are probably ways that we could exploit the synergies there and also lower the transaction costs.

The global picture is more disparate, because we work in five West African countries and five eastern and southern African countries. I think the SDGs provide a good framework for us. They help us choose better leverage points, because we know what the global community is trying to accomplish over the next 15 years.

How do you see foundations coming together to form partnerships to make these kind of contributions as effective as possible?

Foundations combine long-term vision and short-term dynamism. So we can keep our eyes on 2030 as the end point of the SDGs and at the same time consider what needs to happen in the next week, month or quarter in order to get to that long-term target. Most other actors are hobbled by an electoral cycle or a business cycle or a fundraising cycle. Foundations aren’t, but they tend to use the same planning horizons anyway, so they need to look farther ahead than they typically do.

‘Foundations are typically very focused on their relationship with their grantees but that’s not the whole picture.’

Foundations also need to understand the ecosystem much better. They are typically very focused on their relationship with their grantees but that’s not the whole picture. That’s why we helped found and fund the SDG Philanthropy Platform.[1] Its purpose is to increase foundation involvement in the SDGs. For example, if you are a medium-sized foundation in Chicago that has made international grants, you won’t necessarily know the UN system or the political system in the country you’re granting in. If we can help people understand the context and help different actors to find one another, it should enable a lot more foundation activity. The SDGfunders.org website provides great resources.

So are you beginning to see the value of data in terms of being able to document and demonstrate the impact of your work?

We’ve long seen the value of data. The Foundation Center has classified international grants according to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for five or more years now. This allowed foundations to see that they were participating in a movement without necessarily even realizing it. It also allowed them to make the case for their role to other actors, like the UN and national governments. I think data will continue to prove its value and it will allow us to spot the gaps in our work. For example, the global community spent a lot of time on the wording of the goals but not nearly as much on thinking through their implementation or their financing. Foundations could make the case for increased resources in the planning phase and convene the brainpower to think about alternative financing models.

The Gates Foundation is not part of the Philanthropy Platform. Why is this?

I see three bands of engagement in global philanthropy. There’s a top level of foundations, like the Gates Foundation, that are designed to work globally. They hire that way, they know the environment, they have the connections. Then there’s a middle band, where organizations have an ongoing commitment to global work but it’s not all they do, and they may not have the networks or know the policy context of the countries they are operating in. Finally, there’s the lower band of engagement, which is the largest, where organizations focus on domestic issues; the only time they think global is the day after a tsunami or an earthquake. I think the value of the platform is really for that middle band.

Does it help to have Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors (RPA) managing the collaboration?

We could not do this work nearly as effectively if we were trying to run it out of our respective organizations. Heather Grady, RPA’s vice-president, has worked with The Elders, Oxfam and Save the Children. She knows a lot of people and is always on the move – which I think we need if we are to deliver on the promise that we can connect foundations to other sectors. We could easily connect foundations to one another but the real value is to say you need to know this person in UNICEF or that person in UNHCR or this live wire in the Kenyan government – you need to know those people.

With this increased influence of foundations, there are some concerns about private organizations that are not subject to the same democratic controls and scrutiny exerting public influence on the development process. Do you share those concerns?

We need to be continually aware that foundations don’t have a public mandate. While it’s a plus that we don’t have to worry about electoral cycles, they exist to make sure that those in power still have the support of the people. The Gates Foundation has done an exemplary job of comporting itself as if it were a bilateral donor. I think it is subject to pretty much the same scrutiny as USAID, if not more, and it has done very good development work. If we had foundations that were taking a very partisan view, then that could be more problematic. I don’t see that right now.

To what extent is foundation work in the international development field non-partisan? What happens when, say, Catholic views on reproductive health clash with women’s reproductive rights?

We’re not involved in the area of reproductive health, so we haven’t had to sort through those issues. There certainly can be tensions and controversies in this area, and foundations have to figure out where they stand, but I think the priority is for us to work on building a consensus because the problems are so big.

Finally, Los Angeles has issues of inequality, poverty and homelessness. How do you see the Hilton Foundation’s work in Los Angeles itself?

Given that Conrad Hilton’s wealth came from the hotel business and he had an interest in relieving the suffering of the disadvantaged, homelessness is an appropriate area for us to be in. For the last 20 years, we have been working on ways to reduce homelessness in Los Angeles County, which has one of the largest concentrations of homelessness in the country. Our current goal is to eliminate chronic homelessness. We’re talking about people who have been homeless for more than a year or multiple times. Their housing situation is often related to problems of mental illness and substance use.

‘There is a consensus among funders, government officials and academics that the solution to chronic homelessness is not to build more shelters but to provide low-cost, subsidized housing that is supported by mental health and addiction services.’

I really liked the goal of our homelessness initiative when I arrived at the Hilton Foundation. There is a consensus among funders, government officials and academics that the solution to chronic homelessness is not to build more shelters but to provide low-cost, subsidized housing that is supported by mental health and addiction services. We’ve helped to bring the City and County of Los Angeles together, and we’ve brought together a funders’ coalition on ending homelessness. I think LA is on track to end veteran homelessness in 2016, and I believe that we will reach our goal of ending chronic homelessness as well.

For more information

http://www.hiltonfoundation.org

Footnotes

-

^ The other founders are Mastercard Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the UN Development Programme, the Foundation Center and Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors.

Comments (0)