The question may seem irrelevant. Many jurisdictions proscribe partisan or party-political activity and legal rulings in the UK, Germany, and elsewhere in recent years have sought to clarify the boundaries of charitable purpose and activity.

Most would agree that there should be a demarcation between philanthropy and politics placing limits on the appropriate use of charitable resources.

Such demarcations are broadly welcomed in philanthropy. Legal guidance enables trustees of philanthropic foundations to reassure themselves – with a little help from a professional class of lawyers, auditors and accountants – that they make or refuse grants in conformity with charitable purposes. It re-enforces the view that the charitable sphere is the place for private citizens to pursue the public good. In its institutional form, charitable foundations recruit staff to gather and deploy evidence to solve intractable problems in accordance with their purposes. There is no expectation of commercial or personal gain so long as we overlook the highly paid salaries of some foundation CEOs. Moreover, mainstream philanthropists and foundation CEOs delight in their posture of apparent neutrality, rising above the political fray – a force for good unencumbered by grubby electoral and populist pressures.

For all these reasons, the conventional view that the philanthropy universe is separate from both the commercial realm and the political arena is an enduring one. For those providing services to support the poor, volunteering to make their communities better or pursuing other non-contentious activities, no doubt that is true. The boundaries allow the unfettered delivery of good charitable works.

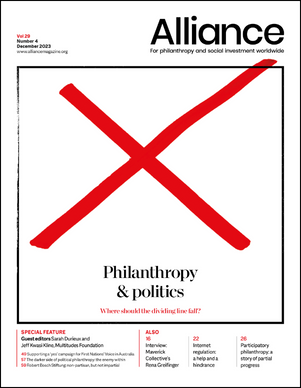

But is philanthropy always a neutral act?

A growing number of progressive voices are challenging that assumption. They argue that philanthropy and politics are inextricably bound and demand that philanthropy assumes a sharper political edge. To them, philanthropy is the pursuit of politics by other means.

Philanthropy’s new progressives will find precedent in interesting places. In the 1980s, conservative philanthropists backed a network of nonprofit think-tanks credited with the rise of the neo-liberal paradigm. That reflected the rightward leaning of many philanthropists who derived their wealth from the fruits of the capitalist system and market economy.

Is the line between philanthropy and politics – while it exists in charity law – existing so sharply in the mind of philanthropists like Marshall? I doubt it.

Today’s capitalism has given birth to a new kind of muscular philanthropy. Take Paul Marshall, the founder of one of Europe’s largest hedge funds, Marshall Wace, as well as the Seqouia Trust, his family’s charitable foundation. Marshall can be credited with influencing the political sphere and wider culture more than most. A committed Christian and Conservative party donor, he funded the successful campaign for the UK to leave the European Union and – more recently – the media titles UnHerd and GB News, the latter alongside Legatum Ventures, a Dubai based company. Marshall has also partnered with its sister body the Legatum Institute – set up by philanthropist Christopher Chandler – to promote its new ‘Alliance for Responsible Citizenship’. The organisation held its first conference in London in October 2023 fronted by conservative firebrand, Jordan Peterson.

Alongside media and political causes, the Seqouia Trust committed £50 million to the London School of Economics’ Marshall Institute for Philanthropy and Social Entrepreneurship. Housed in The Marshall Building, the venture promotes social impact ventures and accelerators and teaching and research on philanthropy and social entrepreneurship. Should this work be seen as separate from his media and political funding? Technically, the answer is probably ‘yes’. But is the line between philanthropy and politics – while it exists in charity law – existing so sharply in the mind of philanthropists like Marshall? I doubt it. Rather, I’d simply see this as the deployment of a spectrum of capital, to use a popular term, to achieve certain goals – strategic philanthropy with a political dimension.

What should progressive funders learn from this?

Today, many eyes are cast towards the future of the Open Society Foundations where a major leadership transition has recently taken place. As the 93-year-old George Soros passed the baton to his son Alexander, can OSF renew its political and philanthropic vision and develop a funding strategy to meet the challenges of the times?

More broadly, will liberal foundations back off or step up in response to the march of conservative philanthropy? That remains to be seen. There are signs that liberal funders are keen to avoid being dragged into ‘culture wars’, instead funding small ‘p’ political projects such as increasing democratic and electoral participation, countering polarisation, and doubling down on support for evidence-based policy-making.

Many will see these measures as wholly inadequate. Demands for progressive philanthropy to develop its muscle and shape up are likely to grow. As it does, they could well learn a thing or two from the – until now – quiet philanthropy of one Paul Marshall.

Comments (0)