‘The philanthropic community should pick up more of the spirit of experimentation of the 1980s and 1990s.’

Crawford Stanley (Buzz) Holling is a Canadian ecologist, Emeritus Eminent Scholar and Professor in Ecological Sciences at the University of Florida, and one of the founders of ecological economics. With over 50 years’ research on socio-ecological systems and networks, he is one of the most profiled and most cited systems thinkers in the world. Why do networks matter, Harald Katzmair asked him.

You are known for your work on resilience and adaptive cycle networks. Could you explain why understanding this cycle is critical to understanding networks and why crises are necessary to networks?

The theory emerged from a group called the Resilience Network started in the mid-1990s and funded by the Ford and MacArthur Foundations. We developed a model of integrative change, which goes like this.

Take, for example, a boreal forest in Canada, where I grew up. When a fire appears, it’s a crisis. The fire is created by the forest, by the accumulation of fuel. The system has become increasingly inflexible and resistant to change. At the same time, it has become vulnerable to a crisis, or even a total collapse – whether from a fire, or an outbreak of an invasive species, or something else. The fire suddenly releases the system’s accumulated capital, which is stored in the trees, the plants and the animals that live in the forest. Yet such a crisis is good because it releases all the constraints on the accumulated capital, which can now be reconstituted in a variety of ways. Typically, it’s quickly reconstituted in a healthy forest.

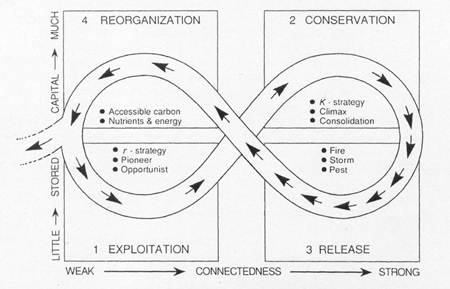

But it’s also a time when unexpected events can occur. It’s an extraordinarily important phase. The system might restart in a radically different way. The key thing is that systems, whether they’re forests or economic systems, reach a point of crisis which can provide the opportunity for experiments. The names are different in different systems, but we see the same pattern of initial growth and accumulation of capital, increasing rigidity, then a crisis, then a period when dramatic new opportunities emerge.

The difference is that in a social system, the changes tend to be resisted by existing vested interests; they want things to continue as they were. This means that in a social system, unlike in natural systems, change takes a long time to start to appear. I feel that’s exactly where we are now, following the financial collapse in 2008. Vested interests are trying to stop transformations in the financial system. They can’t stop them, particularly because of the internet and the networks of people using it to experiment with new ways of dealing with the world. But these experiments are relatively invisible, partly because the media are dominated by vested interests, which makes it very difficult to get a sustained foundation of financial support for them. We are experimenting, but we’re doing it by drawing upon reserves of capital that individuals have accumulated.

For example, I’m involved in an experiment to do with climate change which involves monitoring potential flips in marine systems, all the way from the three oceans that form the Arctic seas right down to the waters of rivers along the west coast of North America. The experiment connects aboriginal communities in those river mouths with the scientific community monitoring marine attributes in the whole of the Arctic. My colleague in charge of the study was having difficulty getting money, so he used his own to buy a small fishing vessel, which he has now fitted out with a laboratory in a box. He can go out to the coast near where we live, in British Columbia, and monitor exactly the same chemical and physical attributes of the ocean that the big icebreakers in the Arctic are monitoring. What we’re trying to do is to get other boats engaged along the coast so that there’s a network of small boats, ideally operated by local people.

The resilience cycle

We call this sort of cycle an adaptive cycle. When it’s healthy, it goes through with sweeps of crisis and reorganization and renewal, and learning continually takes place. If it gets unhealthy, it can flip into traps. When the situation is really extreme, as you see in the Middle East or Afghanistan for example, then the breakdown of the system leads to what we call a poverty trap, where learning slows or stops, or even a rigidity trap, where groups develop such a hostile reaction to change that they freeze any opportunity for learning.

Can you give an example of these healthy cycles?

If we’re talking of social cycles, what is happening in the Middle East now, with the exception of Syria. The so-called Arab Spring was an example of the beginning of a cycle that is searching for renewal.

How do you assess the situation in western countries like the US or Europe?

In the US, vested interests are still dominating the battle, which has produced the kind of polarization that we see now leading up to the presidential election. They’ll break out of that and move into a more collaborative phase, but during that battle it looks really unhealthy! Europe, in my view, is in a much healthier state, though the media identify it as a system in collapse. I see it as a system with diversity, which is one of the key features of a healthy system. Elements might be collapsing – Greece, for instance – but other elements, like Germany or Sweden, are flourishing. It’s a much healthier system for that diversity.

You’ve worked extensively on the idea of an adaptive co-management model for multi-stakeholder networks. I think this type of network will interest people who want to set up or nurture networks. Could you explain this model and how it works in practice?

In the three oceans experiment, mentioned above, we’re hoping to deploy a network of small boats from the local communities along the coast, what we’ve called ‘the mosquito fleet’. You can ignore individual mosquitoes, but not a whole swarm of them. These are small communities whose lives depend upon resources from the sea. They have individuals with knowledge of their immediate world and we are suggesting they expand their knowledge by becoming part of the co-management of the changes that are occurring in their world because of climate change, which ‘cross-scales’, from the local right up to the global. We are trying to involve the school system as well as the individuals with small boats, and the mode of communication is the web, which is used by all involved from the local participants all the way up to the scientists on the big icebreakers in the Arctic. With cross-scale networks the result could be to move deep understanding of local worlds into a deep understanding of the planet in which the local worlds exist.

What are the lessons for philanthropy?

In my experience, the philanthropic world has changed significantly. From the late 1980s to maybe 15 years ago, there was a tremendous amount of innovative philanthropic activity, largely by private foundations like the Ford Foundation or the MacArthur Foundation. It was that support that allowed us to develop the Resilience Network. I don’t find that kind of diverse philanthropic support nearly as accessible as it used to be in the 1980s and 1990s. With the financial collapse, we have new global-to-local experiments emerging, yet funding organizations continue to be dominated by their own culture of giving, which doesn’t support such experiments.

I think what has happened is that these foundations have become more ‘professional’ – that is, they have become more oriented to success and less interested in experiment. Many of their new staff have come from business management organizations, which produce people who are interested in well-ordered and well-structured ways to deal with familiar problems. Such approaches work well when the world is stable, but are very destructive when there’s a dramatically changing environment. Foundations are less amateurish, but fundamentally less innovative.

What do you think should be the priority for philanthropic investors? What would you look for if somebody asked you for money for a project?

First of all, I would look for some foundation of understanding that makes sense of a world that can periodically be in flux. Second, I would look for people who are identifying very specific entry points into such a world. I wouldn’t be looking for people proposing ultimate solutions; I would be looking for experiments primarily. The third thing I’d look for is a network of people who will be engaged in exploring that idea and making it grow into a larger international effort. So it would be context, specific experiments and then people. If I could see excellence in all of those three, I would become very interested in giving them money.

Organizations sometimes come together under the umbrella of a network but trust is lacking. How do you move beyond self-protection into really working together?

We found that lack of trust at the beginning of nearly every workshop we had. The way around it was to recognize that the people you want involved are not only minds, they are also spirits – they like music, stories, limericks. So every meeting had certain features that were focused on motivating and engaging people. And all the meetings had to be held on islands. We found from experience that if you have a group of 50 people on an island without diversions from outside, they create, for a moment, their own society and their own fun.

The second thing was to recognize that not everyone is innovative and open to exploring new ideas intellectually so we used art and literature to engage people. At the first international conference that involved this community, in Stockholm about eight years ago, there was a committee established to find the most interesting kinds of art and music to illuminate the theme, in this case resilience and change. We found that the way to develop commitment among an international network was to recognize that the people you want are good on islands. When we considered whether someone would be good for the programme, the first question we’d ask was ‘Is he/she good on islands?’ and everyone knew exactly what we meant.

What is the relationship between this common identity and the availability of resources?

You have to recognize that in these very innovative programmes a certain proportion of resources have to go to groups or individuals who are not inherently good on islands. We accepted that about 20 per cent of the money would be directed towards activities that at the time were contributing nothing to the whole project, but we had to make that commitment in order to keep the centre of the whole programme going forward. You just have to accept that and hope that these individuals will eventually get to the point where they can integrate what they are doing with the larger purpose. If you’re really doing something novel, there will be a falling away of some people. So resources are extremely important – resources used in a flexible way.

Competition among non-profits for donor money runs counter to trying to build an environment of trust. How do you cope with this intense competition over resources?

Our response is simply to do what we can with the resources we have available, both ourselves and through our networks. The Resilience Alliance, which morphed from the Resilience Network in 1999, for example, includes groups from all over the world that operate with their own resources but also collaborate with others, so the whole activity is magnified. With the ‘mosquito fleet’, we haven’t yet found the money to launch all the small boats we need. But through the Resilience Alliance there’s a project being launched that focuses on early warning signals of what we call ‘regime shifts’ – systems changing dramatically because of climate change. About 15 people, all from the Resilience Alliance, who have worked together in the past, are using their own resources to monitor, and the internet to communicate, early warning signals of systems that are going to flip. We don’t need any money for that, or we need only a little bit of money to meet occasionally.

You once mentioned that we are in the age of the 2 per cent and that people really can make a difference. Yet many people, even those with money, feel powerless to trigger change. What is your advice to them?

First, let me explain why 2 per cent. Surprise and unpredictability lie at the heart of complex systems. It has been said that there are three sets of questions, regarding the predictably predictable, the unpredictably predictable and the unpredictably unpredictable; that is, the known, the uncertain and the unknown. The surprises come from the unknowns and appear about 2 per cent of the time. Those are the times with the greatest opposition from powerful interests but the greatest opportunity for creative innovators.

My first bit of advice is to recognize that you’re not alone, but you’re not a majority. We found that maybe 15-20 per cent of the people who came to our island meetings were truly innovative, in the sense of being fascinated by ideas – sometimes their own, sometimes those of others – and open to working with others, informally initially, to see if a synthesis could emerge. So the first thing I’d say is search for others who are also curious, who are also open to novel ideas, and who are happy to work together in a network.

As for the philanthropic community, they should pick up more of the spirit of experimentation of the 1980s and 1990s.

C S (Buzz) Holling is Emeritus Eminent Scholar and Professor in Ecological Sciences at the University of Florida. Email holling@ufl.edu

Comments (0)