Indian businesswoman and philanthropist, Priya Paul is chair of Apeejay Surrendra Park Hotels and a director of Apeejay Surrendra Group, the family business led by her father Surrendra Paul until his death in 1990. As part of her family philanthropy, Priya Paul chairs the South Asia Women’s Fund, and is involved in numerous non-profits promoting rights and opportunities for women. She talks to Charles Keidan about the springs of her family’s philanthropic work, her views on diversity and representation, and the challenges in a huge and complex country.

How did your involvement in philanthropy start?

My background is not in philanthropy, it’s in business. But as a business family, philanthropy is important because you can’t help but see the disparities of living standards particularly when you live in India.

Also, I went to a Catholic school, so charity and giving back was very much part of growing up. We were living in Calcutta, where Mother Theresa was getting fame for her work at the time. We had just come out of the 1971 India-Pakistan war and there was a refugee problem too.

Was your family always involved in philanthropy?

We’ve always had a family trust which helps us to channel our philanthropic works, the Apeejay Trust. One of my uncles, Jit Paul, was particularly involved. The main focus was setting up schools or other educational initiatives.

In those days no-one talked about what they gave, they just gave. The business was 100 years old in 2010 and one of the things that we did was to identify and fund 100 community initiatives to celebrate our milestone.

How do you decide where to give?

In one sense, our family giving is not that structured or organized. There’s my mother, my brother, my sister and me, and a couple of staff members. If I like something I propose it and if any family member objects, they can raise their objection, but it’s quite fluid, let me put it that way.

Our new strategy at Apeejay Surrendra Park Hotels has been influenced by the 2014 Companies Act, in which the government has mandated that, if you’re a company with a certain amount of equity and wealth, 2 per cent of your profits over an average of three years has to be put into corporate social responsibility (CSR).

We looked at what we’re spending and discovered that we’re already beyond that 2 per cent. But what it prompted us to do was look at how our CSR giving – what we call our Sustainability and Social Responsibility (SSR) framework – aligns with key Sustainable Development Goals.

Based on that, we articulated a policy for the hotel business and chose five areas – community engagement; art, design, culture and heritage; gender equality and empowerment; environment and sustainability; skills and education.

How do you decide how much of your family wealth to give philanthropically?

It partly depends how much you generate from business. Ours is a very traditional real estate business, and I don’t think we generate the same level of income as some European or Western businesses, or some areas like information technology. So we don’t have a rule about how much goes into philanthropy.

And you personally?

I give my time, I give a certain amount of money every year. What I feel I can. But, again, I don’t have a rule.

How much time do you spend on your philanthropic work compared to running the business?

For the past few years I have been chairing the South Asia Women’s Fund, and I am also on other boards. So I spend about 20 per cent of my time on the non-profit side.

When I see the lack of representation of women, whether it’s on boards, or events, those are the things that do concern me.

You’re a woman business leader, a feminist, and with the South Asia Women’s Fund, making sure that women are better represented. Where did the motivation for that come from?

I went to women’s schools, growing up in Calcutta, and then I went to Wellesley College in the US, which nurtures women’s leadership. Hillary Clinton went there, and Madeleine Albright, and many other leaders.

So when I was there, it put this kind of seed in my head about what women could do and basically it taught me that there should be no barriers to what you do.

This was coupled with the fact that ours was a family business and my father was very clear that he wanted me and my sister, who were the eldest two, in the business.

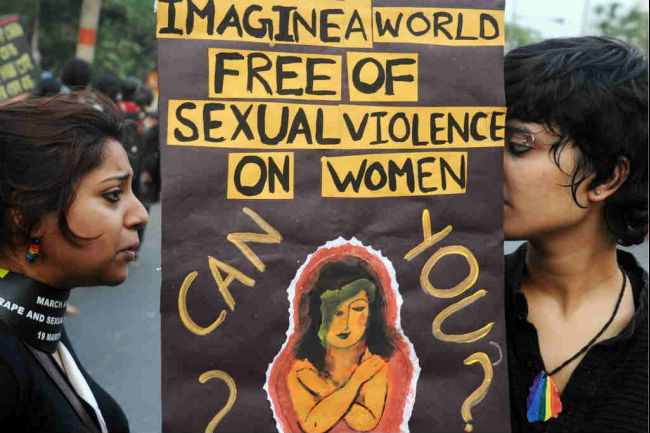

So when I see the lack of representation of women, whether it’s on boards, or events, those are the things that do concern me.

How big is the problem for women’s rights or opportunities in India?

I think less than 30 per cent of our workforce are women.

A law has been introduced that board membership should include at least one woman. Now about 13 per cent of board members are women. It seems like the minimum requirement is being met but some of those may be a male board member bringing a female family member on to the board.

I’m fine with that. That still is an empowering thing. I know people say that these family business people have just brought their women on to the board to meet criteria, but they’re the same family businesses who excluded their women before.

You might think that, in the first year, the women will just say ‘I’ll sign whatever I have to, etc’, but ultimately that situation changes, because women are being influenced by so much other stuff.

But why does the law stipulate just one woman on each board, why not 50 per cent?

Do you know that our women leaders have been proposing 30 per cent representation of women members in parliament, but even in the parties that are proposing it, there’s so much opposition that the bill has not gone through.

What are the grounds for that opposition?

India is very largely a patriarchal society, so while there may be 200 million people in favour of these changes, there are still 800 million on the other side.

Having said that, we’ve had a lot of positive discrimination in government at the local level.

There’s a body called the gram panchayat that governs rural villages and, in that, there’s been positive discrimination in favour of women, which has been very well documented and quite successful.

In India, you still have the reality of the caste system, which creates hierarchies based on birth. Should the laws that require at least one woman to be on boards also be extended to include representation from different castes?

I’m not a great believer in what we call reservations for an endless amount of time. For instance, we have a very peculiar system of getting into higher-end educational institutions that is based on caste. They should be for a limited time until you get that particular group up to a certain level.

If you have, say, a women’s reservation in parliament, it should be say for ten years, and then you let it be. The same with caste-related reservations, which we have in multiple institutions, and in some institutions almost 50 per cent of the seats are reserved for different categories.

Our women leaders have been proposing 30 per cent representation of women members in parliament, but even in the parties that are proposing it, there’s so much opposition that the bill has not gone through.

What about companies?

You cannot have caste-based rules in a company. There are people who are trying to do that and I think it’s completely wrong. I think that you as a responsible company and a responsible person, you should see that there’s diversity.

Why is it right to have these rules for women but not for caste?

Because women really are the lowest, even in the caste distribution. They’re discriminated against in all groups. As far as the workforce goes, women are still very under-represented but it’s also a function of the number of jobs available.

In a lot of cases, men leave their wives and kids looking after their fields in the rural areas, and go to work in the city.

In a lot of cases, men leave their wives and kids looking after their fields in the rural areas, and go to work in the city.

It’s a complex thing. The government has mandated childcare for certain companies, but that’s only in the organized sector.

The unorganized sector is the issue, and you will find actually in the unorganized sector, there are women labourers on construction sites and there are rules that, on some sites, you have to provide facilities so that a woman labourer can work and leave her child there.

So the government is putting in the measures to make it easier for people to work and to get to work. But they’re complex situations and it’s a complex and large country.

Should rules about women’s representation apply to non-profit boards?

I find in the non-profit sector, when you work with women, the board has only women. So, it’s the opposite. You want to get diversity by having a few men in the conversation!

Of course there are many men that work in the sector and men who are very actively involved in those issues, whether it’s human rights for women, or violence against women, but very often I find it’s women talking to women. So in my opinion, we need to get more men on board!

What about women in philanthropic foundations?

My gut feeling is that there are more women in philanthropy in terms of managing organizations. I think that the sector has more women than the corporate sector, definitely.

You have campaigned and shown leadership championing women. Can foundations and non-profits influence businesses and governments through campaigning?

They could, but they haven’t. I have been chairing my own company for a long time so that’s also an example of the fact that women can be in power and can do a good job. But am I part of any network that promotes this?

No, not really. I haven’t gone into it, I’m happy doing the other stuff I’m doing. And I don’t think there’s anything really that organized in India. It’s come through the company law board, but I haven’t been invited to be part of any movement to do it.

In a board, the kind of diversity that’s most important is skills, so that your board has the skills it needs, and it’s certainly important to have all types of backgrounds and of course a gender balance.

And if you were, would you?

Yes, I would. I think diversity of all types is important. Obviously, in a board, the kind of diversity that’s most important is skills, so that your board has the skills it needs, and it’s certainly important to have all types of backgrounds and of course a gender balance.

If you have an Indian foundation that wants to serve the most disadvantaged in society, and especially the poorer classes or castes, how do you ensure that they’re represented in the decision-making of the foundation?

That’s an interesting conversation. South Asia Women’s Fund board has representatives from different fields, but do we have people directly from one of the marginalized communities? No. Are their voices heard?

Yes, on multiple levels. There is a yearly meeting of all the communities that we work in, and they come in and they talk about their issues. Have we helped them? Have we not helped them? Where is their work going? Where do they want to go?

And we listen to them before making a plan and before deciding how to raise money and for what. So the conversations that happen in the field actually shape the programme. It’s not the funders deciding or the people sitting on the board deciding. It’s our job to find funds for groups who are doing the work, rather than the reverse.

Do you see opportunities for people within those groups taking on senior management roles if not board roles?

They could, and there are many organizations where they have done. But South Asia Women’s Fund is a funding organization, we’re not actually an implementer. But the other interesting thing that we do is a lot of women’s leadership, and that’s what helps the organization to achieve success.

So we give grants for travel to attend conferences or leadership events, but we also do a lot of institution building, because that’s how we will measure our success – that we’ve been able to create x number of institutions that can stand on their own and move ahead.

A lot of them are small organizations that are really at the grassroots, so how do you get that? And it may only be three people, but how do you make sure that they’re stable and they’re serving the community? That’s really been the goal of the organization.

Does the Apeejay Trust support the South Asia Women’s Fund or do you do it separately?

I personally support it. There is a programme called Legal Fellows, of South Asia Women’s Fund – first it was in India, now it’s in three or four different countries – where we support and give living grants to lawyers who are working in different parts of the country.

I’m supporting four of them. That gives them their livelihood so they can do pro bono cases, and a lot of those are to do with violence and women’s issues.

And finally, how are things progressing for women in your own hospitality company?

One thing I’d say is that, in our own hospitality company, the number of women employed is at 25-30 per cent, and it’s tough to take it up.

We’ve been actively hiring more women. What we do see with all the tracking is that there’s a lower attrition rate among the women that we hire. In a hospitality business, the hours are long so some staff do drop out, but by and large we find hiring women has a positive influence on many things in the company.

Comments (0)