Last year’s inaugural Next Frontiers conference set the tone for a radical approach to exploring investment and philanthropy. This year’s edition went a step further, with key developments that may well have ushered in a new age of wealth transfer.

With some 460 in person attendees and another 667 joining online, the platform was set for a day of courage, speaking out and visioning “other world’s being possible”, as declared by hosts Yuan Yang and Hettie O Brien, journalists at the Financial Times and the Guardian respectively.

Both demanded in an opening address that all those involved in philanthropy find courage to create exponential change.

“It can feel tough and relentless going against the status quo… showing what’s possible can be exhausting, but also, there is joy and privilege,” said O Brien, before laying out the ground rules that “no one has a monopoly on truth.”

Before panels kicked off in both conference rooms in Kings Place, the audience were invited to pause for reflection and carry out deep breathing exercises. The effect was palpable. A cleansing of the mind, leaving space for new thoughts and being in touch with ourselves.

Keynote

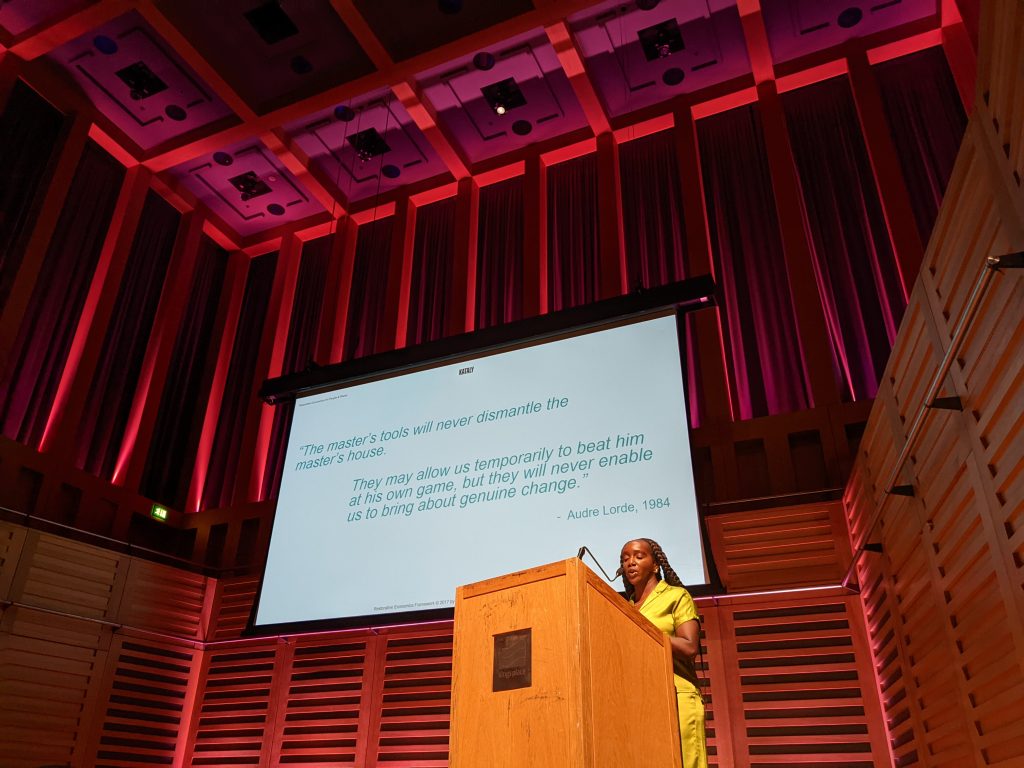

Nwamaka Agbo, CEO of the Kataly Foundation and Managing Director of the Restorative Economies Fund (REF), set the tone for radical exploration as the keynote speaker. She defined her radical approach through the work of the queer, black feminist Audre Lorde – an inspiration for “finding joy and liberation in a world that denied her right to exist”.

“The tools that built this house are racism, sexism, capitalism. All other systems seek to justify repression. It’s not a house I want to live in. As the daughter of Nigerian immigrants, it’s not a house I feel safe in,” Agbo told the 100 strong in-person and virtual audience.

“I want to build a new house, one that gives fundamental human rights. A house governed by principles,” she said, laying down the foundation for a move away from models of philanthropy steeped in colonialism and capitalism.

“We need new tools to build that, or return to the [ancient] wisdoms of native communities. Cultural tools that remember what it’s like to live in balance and harmony with others, even if they’re different from us. [Tools] that prioritise the wellbeing of the collective,” Agbo said.

Her values include supporting black and brown communities, and called on both philanthropists and the communities they serve to “have access to mindfulness practices so they can heal”.

Agbo’s closing statement drew applause from the audience. “This is not an intellectual study. We need to get over this idea that we understand a problem before we act. We are transformed through work. We individuals need to shift how we show up. Do we have the capacity to be in an authentic relationship?”

“The house is on fire”

The first panel talk brought much excitement to the audience.

Just days before, Lankelly Chase had announced that it would disband itself and distrubute its assets within five years. The decision was made acknowledging the roots of their capital in colonialism, as well as a recognition that the traditional philanthropy model is unable to meet the gravity of the global crises we face today.

Now its CEO, Julian Corner, was on stage for the first time since the decision was made public, one that has sent ripples across the industry as it grapples with an understanding that much of the western world’s philanthropy, particularly in the UK and the US, is the child of colonial capitalism.

“It quickly became apparent that we wanted change without knowing what that change would look like,” Corner told panel moderator Indy Johar, co founder of Zero Zero and Dark Matters Labs.

“We needed to step into a space of deep contradiction; being accountable… to community and movements, with the exposure and conflicts that brings to people,” said Corner.

He wanted to navigate “behaviours institutionalised in the sector” while learning from “the margins of community”.

Corner also touched on the subject of trustees and how they “get the blame” from philanthropic leaders.

“I looked at them as the saviours, [which is] a lazy projection. Their question from me was ‘are you prepared to change?’.”

Corner realised that he had to give up the certainties of being a CEO.

“We can’t help but copy frameworks from capitalism. Are those that have held capital in an age of growth, the ones to hold it in the next age?”, he asked, which brought a round of applause.

Dimple Abichandani, fellow at the National Center for Family Philanthropy, tackled the cutbacks taking place in philanthropy, particularly in the headlines after the Open Society Foundation announced a major slash to its staffing.

“We’re seeing a rollback… on commitments to racial justices that weren’t fulfilled. Markets are down, and so are payouts. We are doing less. It’s a truth that has contributed to a paralysis that people are feeling in the sector,” she said.

“How do we move with that and shake ourselves out of the stuck feeling? How do we break out of our deeply held narrative?

Maurice Mitchell, the National Director of the Working Families Party and a community organiser for racial, social, and economic justice, pulled no punches in describing a passivity in philanthropy.

“I can see the house is on fire, and rather than trying to inspire others to put the fire out, there is a spectator attitude to crisis. The activity is how ethically superior I am or factually right I am. What we need is to just solve the crisis,” he said.

He asked leaders and philanthropy to move away from “performance or presentation”.

“Are we reinforcing the status quo? We don’t want to pat ourselves on the back to purely doing activity,” he added.

Johar cajoled both speakers and audience members into finding a new vision.

“We sit at the precipice of a new world view, the end of 400 years. Trauma exists with possibility and we must hold them both.”

Stepping outside the box

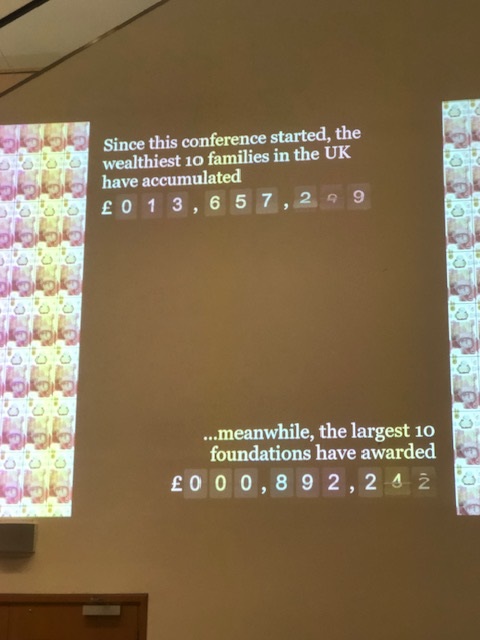

The remainder of the conference continued in a similar explorative vein. A session titled ‘learning to lead change in a complex world’ delved into how to interpret time, to understand whether we currently are in the midst of a period of wealth transfer.

John Schot, founder of Deep Transition, discussed how investments reinforced the industrial revolution.

“We have to move into a deeper change that redirects the economy,” he urged. “Philanthropy must contribute to the shift of an entire paradigm.”

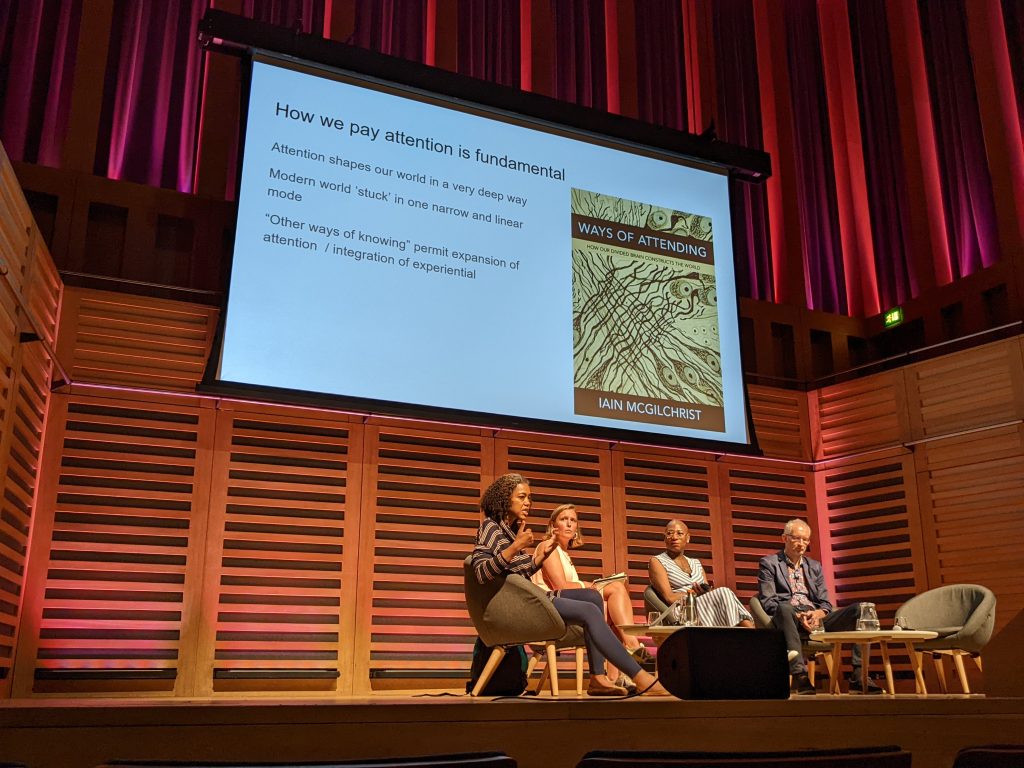

A panel discussion on how philanthropists and those within the sector should take up a practice that goes beyond themselves

He also challenged the idea of impact investing, saying that it only “gets you to a certain level”.

“You must invest without knowing impact for many years,” he said.

“Change takes time,” said fellow panelist Adah Parris, a futurist. “We’ve developed emerging tech at a fast pace, and we have bypassed the questions we should have been asking. We don’t have to see something right now or in our lifetime,” she said.

Parris challenged the audience by bringing together different modes of thinking. For her, nature is a form of technology. Both Shamanism and quantum mechanics come under the umbrella of technology; “we can’t put everything into neat boxes. Thats why we’ve messed up,” she surmised.

The lesson here was for all of us to find “alternative spaces” that we can connect with that, in turn, will help us identify patterns within the sector. Deep reflection, whether it is informed by meditation, religious practice or indigenous wisdom, is essential, say the panellists. Or, as Nkem Ndefo says, “go get yourself an experiential practice”.

From discussions of the future, debates over the past and present followed. A brief ‘provocation’ by Kojo Koram, on how discussions over the legacy of colonialism were “removed from structures of economics and movement of wealth”, and too focused on whether Fawlty Towers should be allowed on TV.

The primary purpose of empire, he reminds us, “was not symbolic. All empires are concerned with material; extortion of material across the world.”

That financial legacy is seen today, with the top three offshore havens located in ‘British overseas territories’ (Bermuda and the Cayman Islands most notably) playing an “insidious role in inequality today.”

“Billions of pounds [are] poured into offshore vehicles, driving up the cost of housing for everyday workers. Even lawyers struggle to afford a decent living in London and Manchester. Part of this is driven by the offshoring of wealth, allowing wealthy to invest in resources people need every day and extract,” said Koram.

He also warned that dismantling financial structures will take more of an effort than the dismantling of statues seen during 2020 and 2021 across the UK and the US.

Ethics and wisdom

The ethics of investing is often a topic that goes without attention. At Next Frontiers, it sparked conversations that opened questions about the kind of society we all want to live in. Panellists all conferred a commonality – that ethics often are laid in our formative years.

Simon Clark, an investigative journalist whose formative years included exploring Pakistan and Palestine, pointed towards an obsession with money as a big part of what holds philanthropy back.

“What hit me was that financial people obsess about abundance of money but not its absence. They’re interested in billions of dollars, not billions of people,” said Clark. “Do we ignore people who have no money? It’s not democratic.”

Influenced by her background in politics and African studies, Delilah Rothenburg, co-founder and executive director of the Predistribution Initiative, wanted to avoid recreating models of co-dependency.

“There is a financial case to be made about thinking about the health of human and natural systems,” she said, hoping investors would work on making new tools that change these practices.

The ethics of investing in private entities was a note of concern for most of the panellists.

For Clark, private entities can play role in philanthropic investment, but should be “constrained”, particularly when delivering healthcare initiatives in developing countries. “The NHS is the model,” he said, with the best investors can do at times is to “pay their taxes to fund universal free healthcare”.

Anita Bhatia, Investment Director at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Foundation, says she has been guided by the “financial trauma” experienced at a young age.

“How can we marry up [the] thinking of ripping off people and then giving back with a pat on the head?” said an exasperated Bhatia.

Next frontiers, new challenges

Whether it was questioning the source of wealth, understanding indigenous perspectives or the psychology of wealth, Next Frontiers stimulated plenty of conversation.

In and amongst the corridors, participants spoke of a newfound motivation to reassess the way they see philanthropy going.

There is no one size fits all. Though, as Next Frontiers 2023 proved, it seems the top-down approach is, perhaps, starting to have its day.

The next frontier beckons.

Shafi Musaddique is news editor of Alliance Magazine

Comments (0)