Philanthropy has often shied away from tackling mental health. Do the reasons usually given for this mask a deeper unease among funders?

As a person who is passionate about both philanthropy and mental health and whose work spans both these realms, it was an honour to be given the opportunity to be the guest editor of Alliance magazine’s special feature on mental health philanthropy. Articles like this often highlight facts and figures – these are very important, because numbers and percentages illuminate the importance of an issue and the progress made in addressing it.

Mental health touches the very core of how we relate to ourselves, those around us and the community and world we live in – so it’s important that numbers and percentages don’t inadvertently depersonalise the issue, and that we don’t overlook the relational aspect of the topic and skip straight to a discussion of problems and solutions.

Mental health touches the very core of how we relate to ourselves, those around us and the community and world we live in.

Paul Connolly of social sector consultants, TCC Group writes that ‘effective’ philanthropy involves balancing ‘humanistic’ and ‘technocratic’ approaches and this has particular relevance to mental health. It is a topic that requires a good dose of the heart, as well as the head – passion and expression, as well as objectivity and evidence.

An ongoing cognitive dissonance

Although mental health is, obviously, a ‘health’ issue, it also has certain distinct characteristics. In some ways, because of its nature, it is more tied up in societal dynamics and cultural attitudes and norms than other areas of health, especially those where it is more obvious a person is ‘experiencing’ an illness.

People experiencing mental illness may not realise they are. Even if they do realise, they may not feel comfortable reaching out to others for fear of the reaction they may get, while those who do seek support from the mental health system may also get let down by it.

Australia, where I live, has come a long way in the last two decades when it comes to awareness about mental health and the support available for people experiencing mental illness. But the mental health system is still far from adequate, and more broadly, the messages given regarding mental health reflect an ongoing cognitive dissonance within society – we say we want to be more supportive of people with mental illness, but they can also be judged or excluded using arbitrary and insensitive generalisations.

If that is the situation in Australia, in other countries, where cultural attitudes have made less progress, it can be even more challenging.

This is starkly illustrated in 2020’s Living in Chains report from Human Rights Watch, which focuses on the practice of shackling people with mental illness. I am Polish Australian, and I can see the role of cultural attitudes from that perspective as well.

We say we want to be more supportive of people with mental illness, but they can also be judged or excluded using arbitrary and insensitive generalisations.

As Raj Mariwala and Natasha Mueller point out in their contributions, globally over a billion people are living with a mental illness and 80 per cent of those live in low- and middle-income countries. Rory White and Danielle Kemmer highlight how mental health is the leading cause of disability around the world and contributes to millions of premature deaths every year.

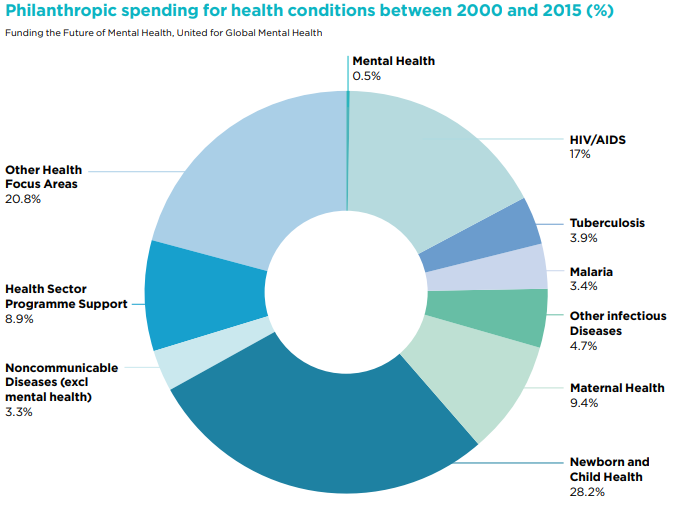

Government funding is still inadequate both within countries and in terms of development assistance, despite efforts to change this. The available data – and it is a bit out of date – also shows that philanthropic funding is, frankly, woeful – with mental health receiving just 0.5 per cent of all philanthropic health spending. When compared against the fact that mental illness accounts for 4.9 per cent of the global burden of disease, it is difficult to summarise it better than in the words of the Funding the Future of Mental Health report from United for Global Mental Health: ‘As things stand, philanthropic spending on mental health is minuscule and fragmented, and does not reflect the needs of the sector.’

This disconnect between societal rhetoric on mental health, the impact of mental illness across the world, and philanthropic action raises a question – does philanthropy have a mental health problem?

In my peer dialogue with Joshua Haynes of the Masawa Fund, his comment about the reticence he’s seen in the case of family offices in particular, was notable. Could it be that mental health stigma is still so strong that some people may be reluctant to fund mental health because it may lead to uncomfortable questions or unsaid insinuations about motivations for doing so?

Could it be that mental health stigma is still so strong that some people may be reluctant to fund mental health because it may lead to uncomfortable questions or unsaid insinuations about motivations for doing so?

While many of us are comfortable to share our own lived experiences, not all of us are. White and Kemmer highlight some insightful research undertaken in Australia by the Future Generation Group (which uses an innovative approach to grow mental health philanthropy in Australia) and EY. The research found that 85 per cent of philanthropic funders that responded believe Australia is facing a mental health crisis – however, only 28 per cent directly fund mental health themselves. It concluded that they are reluctant to do so for a number of reasons:

- Mental illness is complex and the mental health sector is convoluted

- There is significant duplication across mental health delivery

- Most mental health charities have little profile and their messages are not resonating

- Measuring outcomes is a requirement for funding

- They are not aware of their place in the mental health sector

- There are not enough leaders encouraging other funders to invest in mental health

Some worthwhile recommendations are put forward aimed at addressing these issues. However, there is a sense from the research of an ‘it’s not me, it’s you’ attitude among some philanthropic funders.

Striking the right balance?

Two issues identified make me wonder whether philanthropy’s lack of focus on mental health could reflect the fact that it isn’t striking the right balance between the humanistic and technocratic approaches I discussed earlier.

First, as Haynes mentions, mental health is relational. As noted, mental illness is less easy to ‘see’ than many other forms of illness, as are the approaches to supporting mental health. Could the strong and continually growing emphasis within philanthropy on demonstrating ‘outcomes’ and ‘impact’ be part of the problem? Mental health is certainly not the only space where this question is relevant – but could philanthropy be focusing too much on wanting to ‘see’ impact, and is therefore not having as much impact?

To illustrate this with a perhaps oversimplified example: it is relatively easy to evaluate the benefits of bed nets as a way of reducing harm from malaria, so much so that estimates for ‘cost per lives saved’ can be derived, of the kind popular within Effective Altruism.

This is not as easy when it comes to mental health. For example, I have the honour of being chair of Mental Health First Aid Australia International. In the two decades since the programme was first devised here in Australia, four million people have been trained around the world, with mental health first aid now being delivered in 24 countries.

Two issues identified make me wonder whether philanthropy’s lack of focus on mental health could reflect the fact that it isn’t striking the right balance between the humanistic and technocratic approaches.

Guidelines developed by Mental Health First Aid Australia and used around the world are firmly grounded in evidence. They are also rigorously evaluated, and consistently show the benefits of undertaking mental health first aid training. However, it is hard to track the impact of the training on people experiencing mental illness and determine the effectiveness of support provided by a person with mental health first aid training, so it’s not as easy to assess the benefits as it is in the case of malaria nets.

Of course, there are many different ways to measure outcomes and impact, and the evaluation of mental health first aid reflects that, but I wonder if the complexity that needs to be navigated is acting as a deterrent to philanthropy.

Second, it is certainly true that ‘mental illness is complex and the mental health sector is convoluted’. One quote from the research undertaken by the Future Generation Group, also referenced by White and Kemmer, really stood out to me:

‘There’s not really a coherent story about mental health – you know – causes, research, services, what works, what doesn’t. I don’t think there’s a very coordinated picture.’

Practical steps can and should be taken to address this. As White and Kemmer propose, a comprehensive global strategy focusing on mental health is needed, though as they highlight, developing such a strategy is a complex undertaking in itself. But is the lack of a coherent story and the inherent complexity of mental illness and the mental health sector really such a barrier? Or is the bigger barrier within philanthropy itself?

Uncomfortable in the chaos

Could it be that philanthropy, again borrowing the words of Haynes, is not ‘Okay in the chaos?’. Perhaps when it comes to mental health, philanthropy isn’t living up to its ideal of being ‘risk capital for change’, as it expects too much certainty?

The tone of this article may seem rather negative but there are of course developments to celebrate – such as changing societal attitudes to mental health and the progress made in reducing stigma in recent decades (even if there is still more work to do). Mental health is now openly spoken about, as is the need to develop systems and responses that are better suited to the needs of those experiencing mental illness – and despite overall low levels of funding, philanthropy is playing an important role, one which it can and must build upon.

There is a lot philanthropy can learn from charities and non-profits working in mental health, from experts and those with lived experience – and from organisations within philanthropy that are already funding in this area.

In Australia, philanthropy has played a critical role catalysing the development of the Headspace model and leveraging government investment and policy change through the Colonial Foundation’s long-term multi-year support for Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health.

In 2021, one of the world’s largest philanthropic funders, the Wellcome Trust, made a significant strategic shift when it included mental health in its three priority areas.

Hopefully this is the start of a broader shift in philanthropy.

As part of trying to make this shift, introspection could help philanthropy better understand what it needs to change within the sector. It could help avoid externalising – expecting others to change before more funding towards mental health will be allowed to flow.

The reality is that the challenges are likely to come from various directions, and of course philanthropy is comprised of many different organisations, with different approaches, and they will respond in different ways. There is a lot philanthropy can learn from charities and non-profits working in mental health, from experts and those with lived experience – and from organisations within philanthropy that are already funding in this area.

Hopefully this special feature will play a role in shaping this important discussion, and help lead to tangible progress in terms of philanthropy’s role in supporting mental health across the world.

Krystian Seibert is an industry fellow at the Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, and a policy and regulatory specialist at Philanthropy Australia. He is chair of Mental Health First Aid Australia International, and serves on Alliance magazine’s editorial advisory board.

Email: kseibert@swin.edu.au

Twitter: @KSeibertAU

Comments (0)