As this special issue of Alliance goes to print, record droughts in Mexico and the Horn of Africa are affecting millions of people. The failure of harvests, along with higher food prices, raise fears of famine, mass migration and political instability. 2011 was another year of records for extreme weather events, wreaking havoc in places like Australia, Brazil and Thailand – with up to US$45 billion worth of damage in Thailand alone. Seven countries had all-time temperature highs: Armenia, China, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Republic of the Congo and Zambia.

Two new protagonists in this arena – re-insurance companies and military forces – are each in their way looking at climate change as a defining factor of risk and instability. Water availability and food security top the agenda as possible drivers of political and economic risk.

But the resilience of our food system (its capacity to cope and adapt to these changes) is not just affected by climate change. It is also critically affected by the loss of biodiversity and by desertification. (Pictured below: The contraction of the Aral Sea is widely regarded as one of the world’s worst manmade environmental disasters. The ‘ships’ graveyard’ is just outside the town of Moynaq in western Uzbekistan, once the main shipbuilding and fishing port of the region.) These three trends – climate change, biodiversity loss and desertification – are interconnected in rather straightforward ways.

In 1992, the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro devised three separate UN conventions to deal with these global problems. This year sees the 20th anniversary of that event. Despite some positive developments, we have consistently failed to take decisive action on all three accounts. The world will gather in Brazil in June to celebrate ‘Rio+20’, where an optimistic focus on a ‘green economy’ could disguise the unprecedented risks we face.

In 1992, the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro devised three separate UN conventions to deal with these global problems. This year sees the 20th anniversary of that event. Despite some positive developments, we have consistently failed to take decisive action on all three accounts. The world will gather in Brazil in June to celebrate ‘Rio+20’, where an optimistic focus on a ‘green economy’ could disguise the unprecedented risks we face.

As fragile ecosystems, food production, water availability, health systems and shelter are set to become strained in many regions of the world, we believe that building resilience is about to become a defining principle in everything we do: from the allocation of capital and investment to the management of natural resources, economic supply chains and human settlements; to basic accounting principles in business and government.

We have coined the term ‘resilience investing’ not as an attempt to create another buzzword in an already jargon-heavy sector, but rather to initiate a discussion of how the impact investing sector, and the philanthropy world at large, can now embrace the notion of ecological and resource limits and resilience as a central way of defining its ‘impact’.

We identify three ways in which this agenda can now develop, and have invited a broad range of contributors to this special issue of Alliance to provide their views. First, to translate data on ecological trends in such a way that investment by countries and companies is increasingly guided by resilience indicators’. Second, to direct investment to proposals that build the resilience of communities and ecosystems in critical regions. And third, it is especially critical to reallocate capital to influence industries that are accelerating the loss of our resilience, in areas such as energy, food and agriculture.

A spotlight on commodities

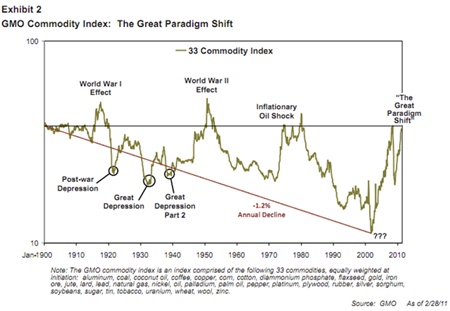

Global investors and an agribusiness industry that is driven by global commodity markets are not helping to manage these long-term risks. According to investment analysts, the now decade-long climb of commodity prices (see graph) is likely to continue given a growing demand for raw materials pitched against the reality of limited resources.

A shift is underway where international investors perceive that owning what grows on the land – or better still, owning the land itself – may be a safer hedge against the risks of more volatile financial markets. For asset management funds in London and New York, fertile land is becoming (in the words of a London-based fund manager) the ‘new gold’. But for countries like China and Saudi Arabia, where water scarcity is already compromising domestic food production, ensuring the steady supply of resources is a matter of national security.

A decade-long rise in commodity prices: the great paradigm shift

These two trends combined are resulting, for example, in large-scale acquisitions of land in regions where the soil is still fertile and water is still available. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, in just 10 years over 100 million hectares have been reportedly leased to investors for agricultural development by host governments often accused of ignoring the interests of communities living on their ancestral lands. In places like Sudan, Mozambique and Ethiopia, land deals are raising widespread concerns over forced evictions and social vulnerability. In the process, a new geopolitical map is being drawn. This pressure for access to resources will continue to challenge the protection of forests, wetlands and, in the case of fisheries, the oceans.

Upgrading country risk profiles

In this special issue of Alliance, Major General Muniruzzaman (Retd) from Bangladesh’s army explains why the military in developing countries is paying growing attention to climate change and resource scarcity. As many as 25 million Bangladeshis are likely to be forced to migrate due to rising sea levels, soil degradation and desertification in the next 40 years, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s conservative projections. The problem stems, among other things, from the unsustainable use of rivers across the Himalayan basin, aquifers and soil. For the government, security concerns include the growing tensions over a (now militarized) Indian border, and the limited capacity of the state to cope with a perfect storm of pressures on its water, sanitation, health and food systems. Despite millions of dollars being poured into Bangladesh in aid funding, very little of it seems to focus on building this type of resilience.

Haiti, for example, shows what the consequences of losing ecological resilience may look like in practice. The loss of Haiti’s forest cover due to deforestation is a well-documented factor in the devastating effects of the earthquake, the inability of the soil to retain water and the collapse of its food production capacity. It will take many decades for Haiti to recover. For countries like Pakistan, the US Army contends, high deforestation rates are raising its vulnerability to extreme floods, further stressing an already volatile region. In fact, most of the areas that have a strategic military importance to the US, from Afghanistan to the Arctic, are facing some kind of ecological stress that could amplify security threats. (Pictured right: Pakistan flood from above. By mid-August 2010, the extreme monsoon floods that had overwhelmed northwestern Pakistan had travelled downstream into southern Pakistan. The lower image, acquired by NASA’s Landsat 5 satellite on 12 August 2010, shows flooding near Kashmor, Pakistan, just before the second wave of the flood hit. The top image shows the region on 9 August 2009.)

Haiti, for example, shows what the consequences of losing ecological resilience may look like in practice. The loss of Haiti’s forest cover due to deforestation is a well-documented factor in the devastating effects of the earthquake, the inability of the soil to retain water and the collapse of its food production capacity. It will take many decades for Haiti to recover. For countries like Pakistan, the US Army contends, high deforestation rates are raising its vulnerability to extreme floods, further stressing an already volatile region. In fact, most of the areas that have a strategic military importance to the US, from Afghanistan to the Arctic, are facing some kind of ecological stress that could amplify security threats. (Pictured right: Pakistan flood from above. By mid-August 2010, the extreme monsoon floods that had overwhelmed northwestern Pakistan had travelled downstream into southern Pakistan. The lower image, acquired by NASA’s Landsat 5 satellite on 12 August 2010, shows flooding near Kashmor, Pakistan, just before the second wave of the flood hit. The top image shows the region on 9 August 2009.)

The collapse of fisheries off the coast of Somalia due to overfishing by foreign industrial fleets is now understood to have been a critical driver that turned fishermen to piracy. The Horn of Africa is a neuralgic point for the world’s trade routes. With now over US$2 billion invested in counter-piracy naval operations, the stewardship of fisheries by the Somali government could have been a more cost-effective measure. However, neither the UN Security Council resolutions nor the naval interventions consider rebuilding the fish stocks as a long-term solution. The new security threats we face due to the Earth’s limits cannot be dealt with using traditional defence solutions. The article by Joshua Reichert, which talks about a mission to establish very large-scale marine protected areas, should also be read against this context.  The case of Somalia suggests how we could connect an increasingly important ocean security agenda with an urgency to protect marine resources. (Pictured left: USS Chosin, the flagship of Combined Joint Task Force 151, a multinational task force established to conduct counter-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia, patrols the Gulf of Aden.)

The case of Somalia suggests how we could connect an increasingly important ocean security agenda with an urgency to protect marine resources. (Pictured left: USS Chosin, the flagship of Combined Joint Task Force 151, a multinational task force established to conduct counter-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia, patrols the Gulf of Aden.)

For most countries around the world, the substantial risks posed by the loss of natural capital are not military but human and economic, and are not properly understood. This ranges from the loss of topsoil in Australia to deforestation in Amazonia, where the reduced rainfall will affect Brazil’s electricity generation sector, 70 per cent of which depends on hydropower. Drawing attention to these risks is a first step to mobilize capital in the right direction and create short-term political incentives to act.

Risk rating agencies, on whose opinion most large investors base their decisions, do not take ecological and resource limits into account in the rating of country risk. According to a recent report by the Earth Security Initiative (ESI), failing to manage natural assets – from soil nutrients to freshwater – must be more closely correlated with a country’s long-term stability, competitiveness and security. One of the areas where we see this being played out, which may be a ‘make-or-break’ for biodiversity, human rights and resource limits, is the global rush for farmland.

The ESI is now convening a group of investors to seek to influence the calculation of sovereign risk ratings in financial markets and its effect on politics. We see future risk indices incorporating data and information on how well countries are managing issues like water limits, soil erosion and land rights. We also envision new coalitions being formed to advance a security agenda where responses are concerned with building resilience. The availability and transparency of information is vital to plan for resilience and to influence the underlying politics.

We see hope in the fact that mainstream investors are beginning to understand, for instance, how issues like soil erosion may jeopardize agricultural investments. For investor Jeremy Grantham, the co-founder of a fund that manages US$93 billion in assets, soil erosion figures among the main concerns in commodities investments. ‘In Australia,’ he wrote recently, ‘where records go back into the nineteenth century, it is clear that more than 70 per cent of arable land has been degraded to some considerable degree. For the planet as a whole, soil losses are certainly higher than replacement, and for some areas, notably in Africa, they are disastrously higher.’

In some cases, as with water limits in given regions, the data already exists but its ‘translation’ from science to investment and politics is weak. The Earth Security Initiative is working with Confluence Philanthropy, a membership network of foundations that seeks to inspire committed funders to align the investments of foundation assets to their missions. We now see an opportunity to jointly create an informed discussion on how to strategically allocate foundation assets within a paradigm of resilience.

Natural capital as a factor in investments

Part of this paradigm shift means viewing the fertility of the soil and the diversity of supporting ecosystems as natural assets that must be taken into account by investors in agricultural projects, as well as those funders supporting food security policies. In an interview in this special feature, Gathuru Mburu of the African Biodiversity Network (ABN) sees a failure of governments and foundations to recognize the role that biodiversity plays in the resilience of family farming in Africa. Mburu sees the continued support for ‘Green Revolution’ solutions as a negative trend. For a few decades, this boosted agricultural productivity by relying on the heavy use of chemicals, mono-crop intensive cultivation and reduced seed diversity. But precisely these factors now threaten to do away with biodiversity and natural nutrients, on which the food system ultimately depends for resilience to extreme weather events. A less diverse system is a less resilient system.

Preserving soils through traditional means and looking to indigenous seeds and small-scale agriculture derived from Africa’s own biodiversity, says Mburu, must be seen as a resilience strategy, focused on both feeding a growing population and adapting to climate change. (Pictured right: Considering natural capital in the production of food. Growing sweet potatoes in the Ngurumo Village in Kenya.)

Preserving soils through traditional means and looking to indigenous seeds and small-scale agriculture derived from Africa’s own biodiversity, says Mburu, must be seen as a resilience strategy, focused on both feeding a growing population and adapting to climate change. (Pictured right: Considering natural capital in the production of food. Growing sweet potatoes in the Ngurumo Village in Kenya.)

Ecological limits are forcing farmers everywhere to acknowledge the importance that a healthy environment has on long-term agricultural productivity. For example, sustaining the microbial diversity of the soil through organic farming methods not only boosts soil fertility, but also helps retain water and sequester carbon dioxide. The article in this special feature by Eko Asset Management and the David and Lucille Packard Foundation envisions a virtuous cycle between agricultural productivity, investment and carbon dioxide sequestration.

Enter impact investing

Investment capital must now begin to move towards projects that increase the resilience of ecosystems and communities and away from those that compromise our long-term security. A wave of experimentation is currently underway, from solar and wind energy to organic farming and new ideas to monetize the value of standing forests as offsets to carbon emissions. As with most experiments, these solutions are not without risks and unintended consequences.

The article by Sergio Oceransky, founder of the Yansa Group in Mexico, describes how the interests of large-scale capital investment groups in wind power in Mexico may have negative impacts on indigenous communities and social sustainability, where land is owned communally. ‘Conventional risk and return concepts,’ argues Sergio, ‘cannot be applied uncritically to investments in “life-supporting assets” in territories inhabited by disadvantaged communities.’

Yansa Group is developing utility-scale community wind farms where communities are the owners of the capital. The idea that equity remains fully in the hands of the community could make many ‘impact investors’ uncomfortable, but their support is needed to advance this model. We welcome this cognitive dissonance, which could help increase the sophistication of the impact investment sector.

As with other groups pioneering these capital ownership models in Latin America, this can be ammunition for a real ‘capitalist revolution’. Equity, after all, means both ‘social justice’ and ‘capital ownership’ and these two definitions, we think, could be critically interconnected.

On the other hand, the interview with Arnold Schwarzenegger, former Governor of the State of California, suggests that where national governments are slower to commit, regional governments can step in to play a catalytic role in encouraging more investments in renewable energy. Schwarzenegger is the founder of the R20, a coalition of regional governments seeking to take immediate action on climate change. Thinking in terms of regions can provide a new way to aggregate investment opportunities. In five years, Schwarzenegger hopes to see at least a quarter of the world’s economy represented by R20 members.

Who will provide the finance? For Ben Caldecott of Climate Change Capital (CCC), one of the world’s first funds dedicated to low-carbon investment, planetary resilience depends on unprecedented levels of infrastructure investment in clean energy. But this will not happen, he argues, without the availability of low-cost capital below market rates. To address this, he has been working to create a series of self-sustained ‘perpetuity funds’ that provide loans for clean energy projects with better terms and interest rates than those available on the market.

Fixing the markets to encourage these investments may require smart coordination. Carl Mossfeldt of Tällberg Foundation describes the work he has been doing with the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), a social movement of 1.3 million women in India, to develop an operation that will involve the sale, distribution and technical service of close to half a million efficient cooking stoves and solar lights by leveraging SEWA’s networks. The recipe for the deal has involved European funders; it is financed through a domestic commercial bank loan of US$14 million, repaid through micropayments and backed by a public guarantee. These experiments are among the hundreds of people and investment funds playing into more sustainable markets which may include new models of waste management, recycling and ‘cradle-to-cradle’ industrial innovation, architecture, water conservation, sustainable agriculture, clothing, transport and so on.

While people may think about extreme weather events instinctively in terms of aid to help recovery, the contribution from Mihir Bhatt from the All India Disaster Mitigation Institute (AIDMI) reminds us that this seldom increases the resilience of vulnerable people. Less than 1 per cent of India’s population is insured against extreme weather disasters. AIDMI has devised an insurance policy for vulnerable communities, which provides a comprehensive cover against disasters for as little $4.50 per year, with potential benefits of around $1,560. The scheme has already reached thousands of people throughout India. We see impact investors stepping in to scale up insurance programmes as a part of this agenda. (Pictured left: Madhubani community restarts livelihoods after the Bihar flood in August 2007.)

While people may think about extreme weather events instinctively in terms of aid to help recovery, the contribution from Mihir Bhatt from the All India Disaster Mitigation Institute (AIDMI) reminds us that this seldom increases the resilience of vulnerable people. Less than 1 per cent of India’s population is insured against extreme weather disasters. AIDMI has devised an insurance policy for vulnerable communities, which provides a comprehensive cover against disasters for as little $4.50 per year, with potential benefits of around $1,560. The scheme has already reached thousands of people throughout India. We see impact investors stepping in to scale up insurance programmes as a part of this agenda. (Pictured left: Madhubani community restarts livelihoods after the Bihar flood in August 2007.)

Reallocating capital

The transition towards a resilience paradigm does not only depend on finding new niches to allocate progressive capital. It also depends, perhaps more importantly, on reallocating existing capital to influence those industries that are eroding our resilience. This ranges from the active shareholder power that individuals may have on companies building coal-fired energy plants to diverting public subsidies that are sustaining practices like overfishing, the rapid clearing of forests or food-based biofuels. Philanthropic foundations have a critical role to play.

The public subsidies that sustain overfishing may be one of the ‘make-or-break’ obstacles to their sustainability. The interview with Kristian Parker, Chair of the Oak Foundation, touches on what it may mean for funders to engage with these topics, by funding advocacy and taking more risks. His work increasingly considers shifting to places where new political visions are more likely to emerge, like Brazil or China, and where there may be more openness from political champions to understand how losing natural capital may threaten the security of a nation.

We are also encouraged by the new generation of philanthropists who are bringing new energy to the sector. ‘We are inheriting the responsibility for the stewardship of money,’ says Sonja Swift of the Swift Foundation in her contribution to this special feature. She suggests that foundations may in fact be key players in accelerating the reallocation of capital that we must now embark on: ‘Foundations need to put their money where their mouths are by shifting their focus from the 5 per cent – grants – to what they do with the much louder and larger 95 per cent: their endowments.’

Humanity is only beginning to understand how much it depends on nature’s capital (a stable climate, rainfall and freshwater, oxygen, fertile land, etc) in order to survive. One day, resource scarcity will incentivize entire new industries associated with greater efficiency. Today, however, it is accelerating a global competition for access to raw materials, increasing the pressure on forests, oceans and freshwater resources and eroding the very capital on which we depend. A new paradigm of investment in resilience must take root in the philanthropy and social investment community, as a way to ensure the prosperity of people and places around the world. We hope that this special issue of Alliance will help set the tone and the direction for many more people and foundations to get interested in this agenda.

Alejandro Litovsky is founder and director of the Earth Security Initiative. Email alejandro@earthsecurity.org

Dana Lanza is CEO of Confluence Philanthropy. Email dana@confluencephilanthropy.org

Comments (0)