Foundation leaders are often heard to make comments that ‘foundations can take risks that others cannot’ or that ‘foundations are society’s risk capital’. But is this actually so? To what extent do foundations currently integrate risk and opportunity into their grantmaking? What can philanthropy learn from the private sector’s approach to risk? What would good practice look like in the area of opportunity and risk? And, finally, how do opportunity and risk figure within the work of foundations as actors on the global development scene?

Social change and large global development issues are complex and uncertain, and thus attempts at change necessarily involve risk. Even when there is robust global consensus about desirable outcomes, it is typically impossible to know with certainty what actions will lead to these outcomes. Most ‘needle-moving’ solutions are also costly, well beyond the means of even the best-endowed foundations. This implies the need to leverage resources greater than one’s own, which decreases control over outcomes and increases uncertainty.

Why foundations are well placed to take risks

Indeed, foundations should be deliberate and conscious about taking the right risks, ie risks where the opportunity for impact is great. Arguably they have some structural protections against risk, which could make them better able than other development actors to take these necessary risks. The fact that foundations have their own resources and considerable autonomy in choosing how to use them gives them a greater ability than governments or non-profits to ‘wager’, and also a greater ability than the private sector to provide ‘patient capital’ that doesn’t need a profit in the short term. They are well placed to start initiatives around which consensus has not yet formed, and they should be able to start processes without certainty of success or short-term results.

In addition to these protections, foundations also have some ‘enabling’ structural features that enable them to take risks. As already mentioned, foundations that make grants are able to set aside, at least temporarily, the requirement of profitability that the for-profit sector is likely to impose, and thus can consider a broader range of approaches. Foundations can nurture approaches that are not yet scalable or ready to be commercialized, but which are nevertheless socially valuable. Further, endowed foundations are structured to exist in perpetuity, and should be able to adopt a longer timeframe than other actors, committing themselves to projects that will take a generation to fully develop, or which may be risky or volatile in the short or medium term.

Playing it safe?

In spite of the complexity of the problems they seek to address, their relative insulation from risk, and their enabling features, foundations in fact seem to be fairly risk-averse, as a number of the contributors to this Alliance special feature point out.

Many foundations feel a need to report very high rates of success in their endeavours, as though their judgment, reputation and integrity would be called into question if they more than occasionally made grants that do not succeed. This in turn leads to an emphasis on predictable outputs and outcomes, and thus to a high proportion of funding for service delivery. This approach does not seem to be localized, for example within the offices of legal counsels. It is common at the programme officer level, in the boardroom, and within foundation leadership.

Indeed it seems that most foundations are not optimizing their autonomy in relation to their resources, and choosing explicitly to make some wagers. Rather, the default position is a prudence more fitting for those who are continually seeking resources from a sceptical public. The opportunity cost of such an approach can be considerable if it keeps foundations from imagining and seizing opportunities, and from investing in things which, as social investor Lance Fors puts it, ‘haven’t even been dreamed of yet’.

There are of course exceptions to this generalization. A growing number of foundations are explicitly building analysis of risk and opportunity into their strategies and grantmaking. The pieces in this issue featuring the Rockefeller and Hewlett Foundations illustrate how risk is central to their work. Other organizations, such as the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, have political risk-taking hardwired into their strategies and actions.

Lessons from investing

It is an irony that endowed foundations regard a diversified-risk investment portfolio practically as an article of faith, continually seeking the right mix of bonds, blue-chip stocks and higher-risk vehicles. Indeed, American foundations have a structural need to invest aggressively in order to meet their 5 per cent payout after inflation. But there is a sort of mental firewall between the diversified investments and the more homogeneous risk profile of their grantmaking.

It may be useful to split the discussion of risk into two concepts from the financial world. The first is volatility, which feels rocky and unstable day to day but should even itself out into an overall positive trend if examined over the long term. This is the type of risk experienced by the broad market. The second is investing in ‘long shots’, the classic ‘high risk/high gain’ wagers which are the territory of venture capitalists. How are these two types of risk relevant to foundations?

Volatility

Volatility in the stock market is about prices, and it should even out over time because the market rewards performance. Being able to take a long-term view that day-to-day volatility will smooth itself out, and that the long-term trend will be significantly positive, is a fundamental concept within investing. Volatility in the social marketplace is harder to track because of the lack of a consistent price metric, but it is also about perceptions of performance and progress.

Volatility is a phenomenon that foundations are well built to withstand, and to work with. Endowed foundations are built for perpetuity. If financially well managed, they should expect to be robust and functional for the long term, and thus able to plan for and work with that positive trend. Almost uniquely among development actors, foundations have the mandate, resources and governance structure to chart themselves a 25-year course. Ironically, an undesired effect of an over-reliance on metrics may be a focus on short-term changes, equivalent to managing a corporation in order to produce quarterly dividends rather than long-term growth.

Long shots

Most of the discussion of risk within philanthropy, however, focuses on the presence or absence of ‘long shots’ within portfolios. Usually, the ‘nine out of ten grants must succeed’ stance is contrasted with a venture philanthropy approach in which seven or eight or nine out of ten grants can fail miserably, as long as one or two or three succeed brilliantly.

But we need more gradation, not just the black and white terms of ‘failure’ and ‘success’. To use the analogy of the explorer’s ship on the cover of this issue of Alliance, imagine a flotilla of ten such ships financed by Queen Isabella, the risk-tolerant funder who financed the voyages of Christopher Columbus. Had she worked through a ‘Queen Isabella Foundation’, this risky project might well have been called the ‘India Trade Routes Initiative’ (ITRI).

Of these ten, imagine that three were strong successes. They bring back cargo that generates an interest in further investment and excites the imagination. These represent efforts ready to progress to the next level, whether it be for-profit investing or government scaling up.

Four ships out of the ten limp back into port, their crews alive but no richer. They have broken even, or nearly done so. There are probably an equal number of positive lessons and negative admonitions to draw from their experience, and both inform the next round.

Three out of the ten ships were total losses, but they have still generated important lessons: courses not to take, lighthouses to be built to warn ships away. Their fate is important intelligence for future investment.

This is not a ‘3 out of 10’ success rate. This is at worst a 30 per cent failure rate, with three very solid efforts and a wealth of knowledge about how to improve the next round of investment

Tradewinds and dragons: the theory of change as an iterative map

We cannot intelligently manage risk without a map that shows where we are trying to go and what we think the routes are. Long shots are long shots not because we don’t know where we want to get but because the routes are iffy. The tradewinds, distances and shoals are not yet known.

There are many elements we don’t understand. In philanthropy, the role of the theory of change is to provide this map.  And just as in early exploration, there are aspects of these first-stage maps that are fanciful or inaccurate. And there are the maps that are simply wrong – one need go no further for an example of this than the story of Columbus discovering America rather than the India trade routes. But as the Rockefeller Foundation’s Zia Khan says in his interview, ‘You often learn more from being specifically wrong than from being vaguely right’, and you learn this because you have written down what you think the lie of the land is, and you keep checking.

And just as in early exploration, there are aspects of these first-stage maps that are fanciful or inaccurate. And there are the maps that are simply wrong – one need go no further for an example of this than the story of Columbus discovering America rather than the India trade routes. But as the Rockefeller Foundation’s Zia Khan says in his interview, ‘You often learn more from being specifically wrong than from being vaguely right’, and you learn this because you have written down what you think the lie of the land is, and you keep checking.

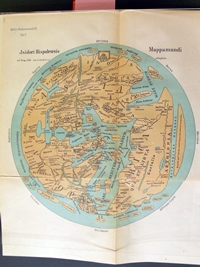

Used intelligently, theories of change are a way to stay focused on an ambitious goal in a complex situation, and to keep one’s eye on several long-shot risks at once. Agreed milestones help to limit the risk of each long shot, particularly in the early stages, but are likely to need revising on a regular basis. (Pictured: 19th-century reconstruction of 7th-century map by Saint Isidore of Seville.)

Suggestions for evolving practice in opportunity and risk

The following are a number of suggestions for how foundations could adopt a more robust and systematic approach to opportunity and risk.

First, foundations should recognize that they have a major role to play in identifying, defining and pursuing promising opportunities to make progress on pressing global issues. Foundations should put the initial emphasis on opportunity rather than on risk. Once the opportunities are identified, discussion should then focus on the place of calculated risk in attaining them. Such an ‘opportunity and risk approach’is more generative and less defensive than simply discussing risk in the abstract.

Second, foundation staff and boards should make opportunity and risk an explicit and regular part of their discussions. The incentive to do so will grow to the extent that foundations actively engage in global development or another ‘collective impact’ effort, because such engagement will make them much more aware of the collective cost of inaction and the value of opportunities.

Third, foundations should build their capacity to assess opportunity and risk, and expand their toolkits. Some may use a ‘heat map’ like the one Pesh Framjee presents in this issue, or ‘expected return analysis’ as practised by the Hewlett Foundation. Using a practice and a tool will increase insight, and will take this discussion from the abstract to the grounded. In doing so, foundations should beware a ‘braggart’s bias’: what programme officer will want to place their grants on the left side of Framjee’s heat map, as having ‘minor’ or ‘insignificant’ outcomes? There need to be less loaded labels, and a more explicit way of describing risk and opportunity.

Fourth, motivated foundations ought to think through how they might best take on more risk. Would the model be to build ‘risk diversity’ in entire programmes, along the same lines as foundation investment policy? Or would some foundations seek to ‘incubate’ a set of long-shot efforts separately from its traditional grantmaking? A third option might be to fund ‘X prize’ competitions, which effectively externalize the risk to the participants, and introduce the possibility of crowdsourcing ideas on opportunities. Of course, all these approaches can also be combined. The point is to undertake a more structured conversation.

Fifth, foundations can build their capacity to work with risk. Here it will be important to find the right balance between short-term predictable accountability metrics and room to manoeuvre (and to fail). It would be useful for foundations to seek and encourage ‘risk-tolerant’ competencies for their staff and boards, including willingness to experiment, tolerance for uncertainty, curiosity, patience and resilience. Foundations should realize that they have a major advantage in being able to work with long timeframes, and build this into their strategy and governance practices.

Sixth, as Rebecca Adamson and Caroline Hartnell’s editorial about the cover image of this issue points out, ambitious approaches are likely to have unexpected outcomes, some of them quite undesirable. These can be difficult to foresee and hard to manage, but they need to be factored in as much as possible, and they point to the need for humility and watchfulness within foundations, and longsighted monitoring outside them. Theories of change should be regularly queried for undesired effects.

Sixth, as Rebecca Adamson and Caroline Hartnell’s editorial about the cover image of this issue points out, ambitious approaches are likely to have unexpected outcomes, some of them quite undesirable. These can be difficult to foresee and hard to manage, but they need to be factored in as much as possible, and they point to the need for humility and watchfulness within foundations, and longsighted monitoring outside them. Theories of change should be regularly queried for undesired effects.

Finally, it’s important to put the right boundaries on the topic of risk. A high risk/high gain approach is justified in areas where the desired outcomes are well beyond the resources or current capacities of foundations and their partners. But there are many areas of philanthropic activity where this is not the situation – for example, as Zia Khan points out, valuable support to emerging and established community foundations – and where an insistence on risk would be irresponsible and distracting. Even the most intrepid foundation is unlikely to take on an across-the-board venture capital investment stance, for a number of reasons, including the intention to exist in perpetuity and thus the need to avoid ‘betting the farm’.

Foundations, global development, and the pursuit of opportunity

A lot of the discussion of philanthropy and risk has focused on climate change and environment, since changes in these areas are both complex and threatening. Since the likelihood of negative outcomes is high, foundations are pressed to take some risks with very unknown outcomes. The Hewlett Foundation is putting a quarter of its resources into policies for reducing global warming, with the explicit admission that there is a low likelihood of success but a tremendously high gain if they can contribute to global success on this issue. What Richard Branson says about geoengineering is striking in its ambitious scope, and frank in admitting what it does not know about the effects, desired and undesired, of what it is advocating. Climate is the ‘Wild West’ of philanthropic risk and opportunity.

But other issues would greatly benefit from a renewed emphasis on opportunity. In education, for example, the risk of underachieving is that human potential is reduced, particularly in the countries and communities that most need innovation, resourcefulness and skill. Global delivery of education is equivalent to a smokestack industry: built on a costly factory-like delivery model, with a relative paucity of revitalizing breakthrough ideas. By most measures, education systems serving developing countries and disadvantaged communities are delivering mediocre results to learners – so getting ‘a little bit better’ is actually continuing to seriously underperform. Such a situation calls out for a risk and opportunity approach.

Within global development, across sectors and global challenges, the complexity of issues leads to several challenges:

- The overall agenda is actually becoming less clear as the 2015 deadline for the Millennium Development Goals approaches without the global system having articulated its vision for the next phase.

- Our ability to forecast well enough to develop long-term (25 to100 year) scenarios and develop related strategies is limited.

- The adequacy of governance structures and steering mechanisms for global common goods is questionable.

- Our ability to innovate rapidly and effectively, either in terms of technology or socially, is uneven.

This list is not meant to be daunting but rather energizing, because foundations can play an important role in clarifying each of the above issues. Each item on the list is also clearly an opportunity. Philanthropy as a whole should continue to signal its intention to help to work out these questions. Individual foundations and groups of foundations naturally need to take on ‘smaller chunks’ in order to be grounded and effective. But they should take those chunks on as pieces from a greater whole, and they should push themselves to identify the most promising opportunities and take risks to attain them.

Peter Laugharn is executive director of the Firelight Foundation. From 1999 to 2008 he was with the Bernard van Leer Foundation, for the last six years as executive director. He has been actively involved with the European Foundation Centre and the Council on Foundations for many years. Email peter.laugharn@firelightfoundation.org

This article from our guest editor is the first of a number focusing on the topic of opportunity, risk and global development.The full special feature is available to read online for subscribers to Alliance magazine. If you do not yet have a subscription, discover more about the options available.

Comments (0)