As Michael Clemens argues in this issue, allowing more migration to wealthy countries is one of the most powerful strategies for reducing global poverty. However, immigration policy is a matter over which receiving countries often exercise almost unilateral control, and they have rarely supported larger inflows. What can foundations do to help?

In the US, while foundations have been supporters of stronger protection for migrants once they arrive, they have rarely supported advocacy to allow more migration. A big part of the problem is that the potential immigrants aren’t there to advocate their own interests with either funders or the public.

Another reason foundations have overlooked migration is that it falls between domestically oriented funders and those focused on development abroad. For domestic funders, migrants who haven’t arrived yet are obviously outside their scope. For development funders, as Oxfam’s Duncan Green has observed, migration is often seen as a failure in sending countries, a problem rather than a solution.

‘Sometimes, we support development ‘over there’ so that ‘they’ won’t show up over here. This is both empirically and morally mistaken.’

Sometimes, this is made explicit: we support development ‘over there’ so that ‘they’ won’t show up over here. This is both empirically and morally mistaken: more people, not fewer, are likely to migrate from low-income countries as they become middle-income countries, and we should care about improving the welfare of individuals, not of countries.

The potential gains of remedying the structural lack of funding in this area led the Open Philanthropy Project to prioritize pushing for more open immigration policies. The Project, where I work, is a collaboration between GiveWell, a US non-profit, and Good Ventures, a foundation established by Cari Tuna and her husband Dustin Moskovitz, co-founder of Facebook.

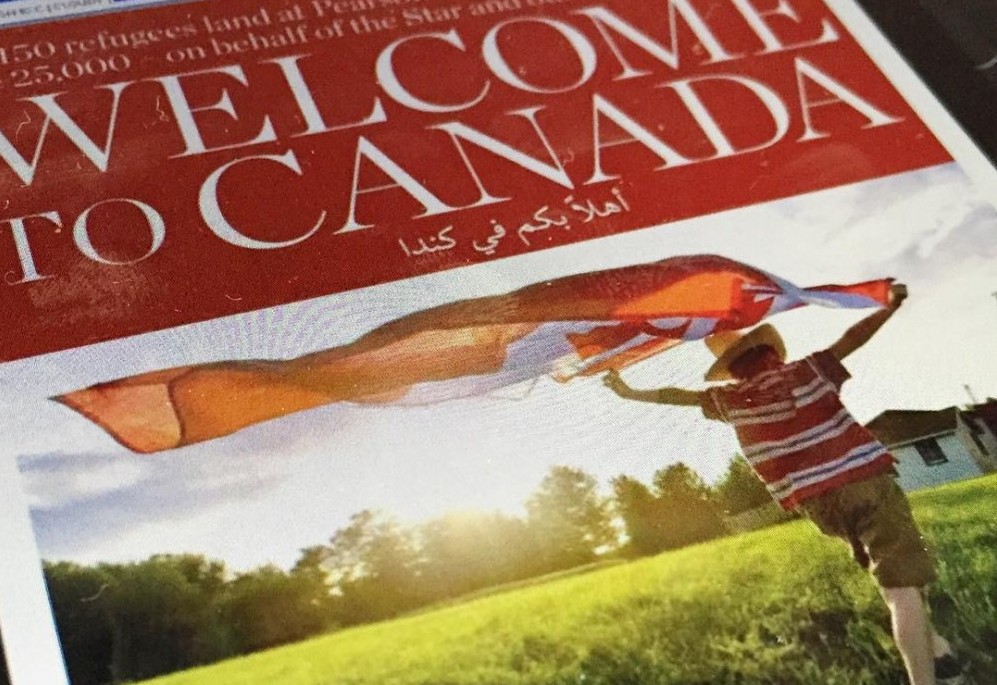

Canada’s Private Sponsorship of Refugees programme is a good example of philanthropic support for private resettlement and citizen engagement. Credit: Dom’s World

Because there is so little organized support for this aim, a funder looking for advocacy opportunities on this topic faces a lack of obvious grantees. In summer 2015, we worked with the Center for Global Development to convene a number of scholars and advocates to discuss potential strategies and organizations that could help promote global mobility. We posted notes from the meeting but I wanted to highlight a few ideas that might help other funders:

- Immigrants’ advocates Most existing groups focus on protecting the rights of migrants who’ve already arrived, but promoting the idea that immigrants are a benefit rather than a cost to receiving countries may help create openness to immigration in the long run.

- Private refugee sponsorship Canada’s Private Sponsorship of Refugees programme is a good example. Philanthropic support for private resettlement could potentially increase the number of refugees resettled and engage citizens with resettlement in a way that makes them more potent and dedicated advocates.

- Ethical job facilitation for potential migrants Many employers rely on undocumented workers or use labour brokers and recruiters that violate migrants’ rights. New exchanges or facilitators committed to ethical recruitment practices could protect migrants and increase the returns to them and their families.

- A social innovation and policy ‘think and do tank’ Such an institution might pair academic researchers with policy entrepreneurs to promote small changes to immigration policy or practice, such as allowing more visas to a sending country after a natural disaster, or creating a programme to increase take-up of an under-used migration opportunity.

- Supporting pro-immigration organizing within other interest groups Whether this might be helpful, and which groups would matter, would depend on many factors in a given receiving country.

A funder might also start with the idea of supporting domestic, rather than international, migration. There is evidence that domestic migration can lead to better outcomes in some low-income countries, as well as in large high-income countries like the US. Trying to remove barriers to domestic migration might be considerably easier than barriers to international migration, though of course with significantly smaller benefits.

The Open Philanthropy Project is still exploring how best to prioritize our own funding in this space, so I welcome any guidance readers might have to offer. I would also be curious to hear from other funders who are looking for opportunities to allow more immigration to reduce global poverty.

Alexander Berger is a programme officer at the Open Philanthropy Project.

Email alexander@openphilanthropy.org

Comments (0)