‘A very unusual foundation,’ is how Guy Weston, chair of the UK’s Garfield Weston Foundation (GWF), describes his grandfather’s creation which celebrates its 60th anniversary this year. Few would disagree. Not only is the foundation’s structure uncharacteristic of British philanthropy but its approach is unusually straightforward with a focus on listening, supporting and empowering its partners. Although it is Britain’s second-largest foundation with over £12 billion in assets, few will have heard of Garfield Weston – apart from its hundreds of grantees. But, as its director Philippa Charles tells Charles Keidan, the real story has never been about the foundation….

‘I think more foundations do core funding than maybe charities are aware. The more of us that do it, the better.’ Phillipa Charles.

What’s the structure of GWF?

When Garfield Weston set up the foundation, he put 80 per cent of the family business into trust for the benefit of the nation, which is effectively in a holding company, Wittington Investments. Wittington holds the majority shareholding of Associated British Foods (ABF) which is the real business, if you like. It’s not just food but retail and a broad range of things including the Grand Hotel in Brighton and Fortnum & Mason in London. I love ABF. In fact I used to work for them before I moved to the foundation 10 years ago. I think there’s something very straightforward about the company – it makes bread, milk, tea, sugar, socks, knickers.

Why did Garfield Weston set it up?

As part of our 60th anniversary celebrations, we’ve produced a book to showcase the charities we support. In it, Garfield Weston sets out what was behind his vision in his own words. The ethos was very enlightened but also very straightforward. It was about backing talented people who have good solutions to meet the needs in their communities, whatever those might be. And at its heart, that’s exactly what the trustees still do. We don’t tell people what to do with the money. Rather, we allow those who are closest to their beneficiaries to come up with the right solutions for them. We’re also very respectful of people. We don’t use complicated jargon and we try to be really accessible.

I’m also very fortunate as I don’t just see the trustees for one or two meetings a year. They are around all the time, and that has a number of really big advantages. If something crops up which I’m not sure about, I can just go and ask them. The chairman’s office is literally next door. They put a huge amount of time and effort into their Foundation. I love the fact that they really care and that they’re out and about all the time, visiting grantees, having meetings, doing due diligence. The fact that we’ve got a board that rolls up their sleeves means that we can manage with a small staff. I’ve got a team of four, plus an assistant who doesn’t just manage my diary, she also helps charities because she’s worked here longer than I have, and she understands this place.

I’m also very fortunate as I don’t just see the trustees for one or two meetings a year. They are around all the time, and that has a number of really big advantages. If something crops up which I’m not sure about, I can just go and ask them. The chairman’s office is literally next door. They put a huge amount of time and effort into their Foundation. I love the fact that they really care and that they’re out and about all the time, visiting grantees, having meetings, doing due diligence. The fact that we’ve got a board that rolls up their sleeves means that we can manage with a small staff. I’ve got a team of four, plus an assistant who doesn’t just manage my diary, she also helps charities because she’s worked here longer than I have, and she understands this place.

Yet, with such a small team, you are administering an endowment of over £12billion and you contribute very significant funding – over £60 million in the last year.

Yes, and hopefully this year it will be £70 million. Because the biggest chunk of the endowment is a FTSE50 business, it fluctuates in the same way that the share prices fluctuate. There’s a really interesting symbiotic relationship. ABF and the wider business can plan long-term. Being owned by a charity which has a long-term time horizon means they are not buffeted by the short-term demands of financial returns. As a result, they have been able to invest and grow. Our donations have grown, too, so it’s created a real virtuous circle.

So how the business fares shapes the rate of philanthropic spending?

Absolutely. We will have given away a billion pounds by the end of this year, but half of that has been done in the last ten years. We’re in a fortunate position to be able to give a lot away. There are a number of reasons we can do it effectively. One of them is that the applications come in nice and steadily, and I think that is a feature of having been around for a long time.

So you have existing relationships with a lot of grantees?

Yes, and that is helpful. If they all came in on 1 January, I think it would be pretty sticky. We’ve also invested in a good database, and we’ve got clear processes. I’m a big fan of keeping it simple. When one member of staff has a relationship with a charity, you maintain that. You don’t parcel it in different stages to different people, because every time you do that, it risks falling through the cracks. A very large percentage of what we do is very straightforward but makes a huge difference like providing basic facilities for communities. It could be putting a new roof on your village hall. That’s £70-80,000 – a lot of money for a community to raise. Yet without that, there’s nowhere for mother and toddler groups, the elderly groups, the keep-fit classes, meals on wheels, and other services. And because they’re straightforward, they’re easy to evaluate. They send us their proposal and a number of different building quotes. We’ve got pretty good over the years at knowing an appropriate cost for things. It’s because of these sorts of funding needs that we decided to launch the Weston Anniversary Fund this year, to help small charities get funding for capital projects up to £150,000.

A very significant number of your grants go to churches. Is that because faith inspires the foundation’s philanthropy, or because churches deliver services that benefit communities?

The latter. Communities tell us all the time how important churches are to them. Even if they never go to church, they realise that the church is not only part of their architectural heritage, but quite often it’s the only space in the area that’s big enough to hold 100 plus people. If it doesn’t have a toilet or the ability to make tea or coffee, it’s pretty limited. But there’s no religious emphasis. We’re just as open to, say, Muslim charities and Sikh organisations.

Core funding is something that the Foundation has always done. We’re not responding to any kind of fad or fashion. The funny thing is – though this has lessened slightly now – charities have often struggled to ask for it. I have to encourage them, because they are so used to having to parcel something up to look like a project. I think it’s a breath of fresh air for them to hear us say ‘please do apply for core funding’.

As well as capital funding, you are also known for providing core funding.

Again, it’s supporting what the charities need most in order to their best work. One year, it might be an extension, the next, it might be employing an extra member of staff.

In the last ten years, the British charity sector has been through a lot and is continuing to go through a lot. It’s important that a funder can be a constant support to the sector and be reliable

Why do you think relatively few of your counterparts are willing to commit that kind of flexible core funding?

I think more foundations do core funding than maybe charities are aware. The more of us that do it, the better. Core funding is something that the Foundation has always done. We’re not responding to any kind of fad or fashion. The funny thing is – though this has lessened slightly now – charities have often struggled to ask for it. I have to encourage them, because they are so used to having to parcel something up to look like a project. I think it’s a breath of fresh air for them to hear us say ‘please do apply for core funding’. If our trustees are convinced by what they do, the capabilities of their team, their leadership, the need, all of those things, why wouldn’t we trust them to do a good job of it? And they let us know if something changes or doesn’t go according to plan. These things happen, and dealing with them comes down to good communication.

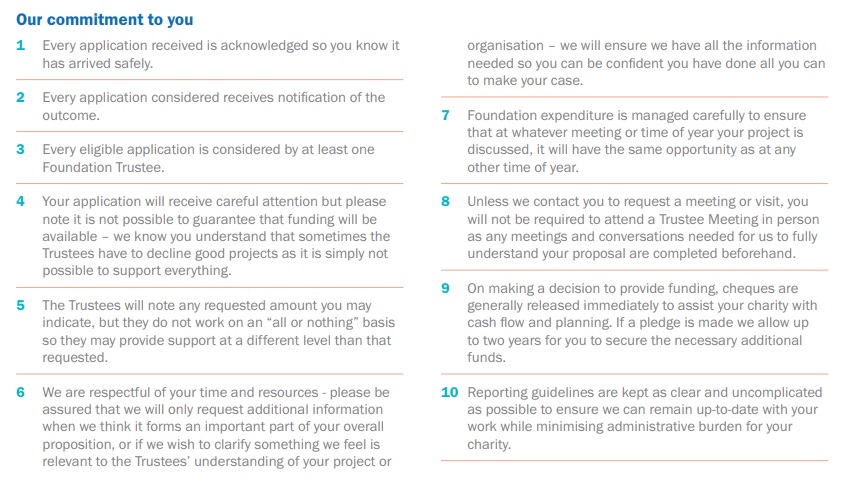

In the Weston Charter which you’ve produced to help grantees know what to expect, it notes that one of your trustees sees every eligible application.

That’s a very important principle. It’s something that we’re proud of because it means that charities know there isn’t some faceless bureaucracy making decisions about their proposals. The trustees also believe that it’s important to have more than one perspective. Ultimately, it’s their call, and it’s our job to support that, but they want people to offer a view. They may or may not agree with that view but the debate is an important part of the thinking process.

That’s a very important principle. It’s something that we’re proud of because it means that charities know there isn’t some faceless bureaucracy making decisions about their proposals. The trustees also believe that it’s important to have more than one perspective. Ultimately, it’s their call, and it’s our job to support that, but they want people to offer a view. They may or may not agree with that view but the debate is an important part of the thinking process.

The Charter is unusual in that it makes a commitment from funder to grantee.

That’s why I did it. We have a commitment to being really straightforward. It occurred to me that if that’s the way we work, why wouldn’t we tell people? I confess, though, that when we published it, I wondered if people were just going to laugh, and think ‘that’s so simple, is it really worth it?’ But we were inundated with responses. It’s been out there for several years now and we still get feedback saying, ‘wow, this is amazing!’ To me it’s not amazing, it’s obvious.

As you said, much of your work is in providing community facilities, but do you have some basic strategic divisions between, say, community, health, faith?

We do, but decisions rest more on explaining something to people clearly, than on whether it belongs in a ‘health’ or a ‘welfare’ box. For example, if a local church is doing a meals-on-wheels project for elderly people to help them live independently and to look after their nutrition, is that welfare, is it community? I don’t care what box we tick and our trustees don’t. What we care about is that our money is used well and serves a purpose, not on how much we want to spend in Leeds, or on youth.

So within basic parameters, you’re willing to simply open up and listen to the needs of the charitable sector?

I think it would be crazy not to. It’s really important to us that we don’t make assumptions about what is behind a change. Sometimes, because we’re constantly evaluating, we do see themes that the charitable sector isn’t able to see. We commission research to investigate it properly and to make sure that subsequent funding decisions are solving the right problems. That’s where we have to get the local population, or the sector we’re looking at, to tell us so that we can try and put the right things in place. For instance, we commissioned research in the North East [of England] because we could see that applications were falling about five or six years ago and we wanted to understand why.

This has led to an ongoing process. We learned things from that research which were slightly uncomfortable. We thought we were very accessible and that anybody felt fine coming to us. But what we found was that there was a barrier for people because our address is in London, even though we all work all over the country. Those who already had a grant from us were confident enough to reapply, but the ones who had a need, but who didn’t have a previous relationship and didn’t know anyone else who knew us, didn’t come to us. Some of the people who need us most feel least able to ask, and that insight was the crux of the very clear strategy that we have developed in the North East.

This isn’t about building our profile. It would have been very easy to go and make a big splash but what we actually needed to do was light a series of small fires. I have a very strong view that it is very rarely one intervention that does the trick anyway. You actually need to do a whole series of things that may seem separate, but are interconnected – building capability and capacity and, through that, building confidence.

Pilotlifght offers charities and social enterprises access to the strategic business support they need to become more efficient, effective and sustainable.

And how did you do that in North East England?

We’re still doing it. One of the things was the Weston Charity Awards. I approached Pilotlight a charity that uses volunteer business mentors, who work with charities to redevelop some aspect of their work. Together, we launched an initiative to get people in the North East to apply, and have the benefit of its business mentors. The Awards have been going now for five years and we’ve extended them to the North West, Midlands and in Wales. We’re also working with the Cranfield Trust, which uses experts and business mentors.

The Pilotlight approach is not for every organisation. It’s quite a lengthy process and sometimes an organisation just needs help from a really experienced fundraiser or somebody who is really good at marketing. We also partnered with the Community Foundation for Tyne & Wear and Northumberland. Unusually for us, we were a little more directive than normal. We said we’d like to fund a person at the community foundation to work with communities, to run events and programmes, to build capability and to help people become more aware of the issues.

How’s that partnership gone?

It’s working well and it’s still going. In fact, in the second year, the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation came in as joint funders. One of the things that we found in the North East is that people wanted to do more, but they didn’t always have the connections or the know-how. So if we could put some interventions in place that helped with that, we were helping them help themselves. And ironically for a funder, we don’t think that funding is always the solution. But of course funding helps. Underneath the mentoring involved in the Weston Charity Awards, they also receive core costs funding to support the process.

For us, profile is about supporting charities better. So if being visible encourages people to come to us and apply for funding, then it’s worth doing. We don’t want to be known for our own sake.

So partnerships are a really important element in your approach to philanthropy?

Totally. Partnerships are a really good way of doing far more with what you’ve got. I had the idea to use business mentors to build capability, but why would I create that when Pilotlight had an absolutely fantastic model. Our trustees see the leverage effect because actually what we are doing is helping Pilotlight grow too.

Has your approach changed in 10 years of doing your job?

Has your approach changed in 10 years of doing your job?

There are very few constants. In the last ten years, the British charity sector has been through a lot and is continuing to go through a lot. It’s important that a funder can be a constant support to the sector and be reliable. Initiative-‘itis’ is not the way to make change, in our view. I think it’s about being consistent, listening to what your beneficiaries need and then adapting your solutions – the funding, connectivity, partnerships and collaborations – to meet that need rather than telling them what they should have.

What do you see as the main changes in the sector?

I think chief executives are dealing with an unprecedented level of complexity. Not all the layers of that complexity are bad. For example, the way that we use media makes information immediately available, which is a good thing, but it’s also something that a chief executive has to respond to and adapt to very quickly. Media scrutiny has rocketed, and in some cases for very good reasons. On the upside, I hope donors are perhaps more thoughtful about where they put their funding. Information is always good – that’s where I think the media play a really important role in informing people. But that comes with responsibility, too.

Would you also like to see foundations more in the spotlight, being more visible than they were previously?

For us, profile is about supporting charities better. So if being visible encourages people to come to us and apply for funding, then it’s worth doing. We don’t want to be known for our own sake.

Do you think publicity would encourage other funders or other people in comparable positions to look at the model you’ve adopted?

Our trustees are very independent and assume that other people will also have the ability to make their own good decisions. So if something we do encourages somebody else, then great, but it won’t be because we’ve told them to do it, it will be because they like what we’re doing. That being said, we can play a role in alerting the sector to issues, which is what we’re doing with the core funding issue. It’s sometimes a delicate balance, and, to be honest, giving interviews like this is not a natural activity for us.

I know some family foundations bring people with specific areas of expertise, or the perspectives of beneficiaries onto their board. Has Garfield Weston any plans to do that?

I know some family foundations bring people with specific areas of expertise, or the perspectives of beneficiaries onto their board. Has Garfield Weston any plans to do that?

It’s in our deed that our board of trustees are descendants of the founder by blood. But he and his wife had nine children, so it’s a big family and actually if you look at our board, they are very well-educated, they come from different parts of the world, they’ve all been involved in various businesses and charities, so they bring an enormous amount of expertise and passion. And we’ve got more women on the board than men, which is rather nice.

How would you sum up your job?

My job is very simple. Two things – it’s to support great charities to have a fair chance and fair access to funding, and it’s to support our trustees in tricky decision-making. That’s it.

Comments (0)