Twenty-five years ago, in 1989, Klaus Jacobs, the founder of many leading global companies such as Jacobs Suchard, Adecco and Barry Callebaut, established, together with his family, the Jacobs Foundation in Zurich to improve the development opportunities of future generations. Klaus’s son, Christian Jacobs, who now chairs the foundation board, talks to Caroline Hartnell about how the foundation has developed, the thinking behind its annual prizes, its new approach in Africa, and the shift in focus towards early childhood development.

You have been on the board of the Jacobs Foundation since 1995 and chair since 2004. How has the foundation changed over that time?

It has changed quite a bit but what has not changed is our central focus – child and youth development, by which we mean essentially improving the living conditions of young people – and our ‘evidence-based approach’ to it. We want to be sure that in any programme, we do not only spend money, but we also make sure there is some know-how involved or some new insight which is an assurance for us that our programmes have a realistic chance of being sustainable and having an impact. I’ll turn it the other way round: if you do not have evidence that your programmes have some sort of new insight, the reason to keep them going after the funding period ends is not as strong as it would be if there were some evidence that what you’re doing is really new and effective.

So what has changed?

Several things have changed in the process of what I usually call professionalization. We now develop thematic priorities where we think the foundation has a lever to improve living conditions. That’s the first point. The second point is that, like many other foundations, ours was very much run by the board at the beginning, whereas now our professional management team runs the programmes. Third point, and this is rather new, is that we develop five-year plans, which we call mid-term plans. So we are now running our second mid-term plan from 2011 to 2015.

The fourth point, and this really has changed, is that we now have much more money. Until 2001 we had an annual budget of about 5 million Swiss francs. Then my family transferred the beneficiary ownership of all our companies into the Jacobs Foundation. The budget is now around 35 million Swiss francs, and if you increase the budget by that much, of course there is a mindset change.

Finally, we pay more attention to accountability, partly as a result of the increased budget. We try to measure our impact on improving living conditions and we have developed key performance indicators so that we have an aggregated view of the result of our activities. This is easily said, but very difficult to introduce and even more difficult to operate.

So, we have changed in these five respects, but not in our goals.

You have three family members in a board of nine, and the family are after all the funders – what role do they play? What drives change within the foundation?

The family understands itself as an investor and investors do not usually consider themselves as running a business or a not-for-profit organization; rather, they rely on excellent management, and on board members. We rely on a good connection between the management, family representatives on the board and non-family members, but in the end it’s the management who run things.

You asked what drives change. As I said, it’s important that the foundation has a crystal-clear cornerstone: an evidence-based approach to child and youth development and an international orientation. We select countries where we can really make a difference and we always look for the greatest opportunities to create change.

Did things change dramatically after your father died in 2008?

If a leader dies, and especially if is he is your father, it always leaves some sort of vacuum, but I think at the time we had already pretty much defined the cornerstones of the foundation and of our family, so the change was not so big. Look at the six guiding principles of our family: global trading, youth and talent, sustainability, innovation, personal engagement, and excellence orientation. These haven’t been touched for 30 years.

You established two annual prizes in 2009. Apart from honouring your father’s memory, what was the thinking behind this?

The awards honour outstanding achievements both in research and in practice in the field of child and youth development. We wanted to showcase ways of improving the living conditions of children and youth, and we thought the best way to do this was by creating a highly respected annual prize. So the prizes both honour my father and show the extraordinary people – both in research and practice – contributing to child and youth development.

I think it’s very important to a research prize to get a fantastic jury. We would not have started it without having such a jury. We also try to relate the awards so people understand the link between research and interventions. So, for instance, the 2014 research prize went to Canadian neurobiologist Michael J Meaney from Montreal for his research on how childhood experiences, including parental behaviour, can become embedded in children’s biology. This suggests that in the future it might be possible to identify children who are most at risk and put appropriate interventions in place – something that we had not previously thought of.

From left to right: Christian Jacobs; 2014 research prize recipient Michael J Meaney; 2014 best practice prize recipients: Philipp Chimponda, Beth McKenna and Father Baxter of SHARPZ.

We gave the best practice prize to SHARPZ (Serenity Harm Reduction Programme Zambia), which uses evidence-based cognitive behavioural therapy to address the needs of children and their families who are affected by severe trauma. The SHARPZ programme works with orphan children in Zambia, which is one of the African countries that is most badly affected by the HIV/AIDs pandemic – almost 80 per cent of the population is affected, directly or indirectly – thus showing that interventions can work even when they’re low-resourced and conducted among a high-stress population. Both awardees are outstanding and the work of each perfectly interrelates with the other.

What proportion of your money goes to international programmes as opposed to Swiss programmes?

It varies. We allocate funds on the basis of what’s needed. In our engagement with the University of Zurich or the Jacobs University in Bremen, for instance, we did not set up a rigid financial plan from the outset but rather were looking at what amounts were necessary to achieve the goals that we wanted to address.

At the moment, we are thinking about a major investment in Africa, based on our existing programme there called Livelihoods. The Livelihood programme is about improving the living conditions of children and their families by increasing farmer incomes. We initially thought that just by doing that, we would achieve an improvement in living conditions, but we came to realize that additional income for farmers does not necessarily achieve this on its own. The new programme therefore makes much stronger connections between community development initiatives and the measures supporting farmer productivity and ultimately increased incomes. These community development initiatives range from child protection issues to education, youth inclusion and women’s empowerment. We think that a holistic approach like this is more likely to have a sustainable effect on the improvement of living conditions.

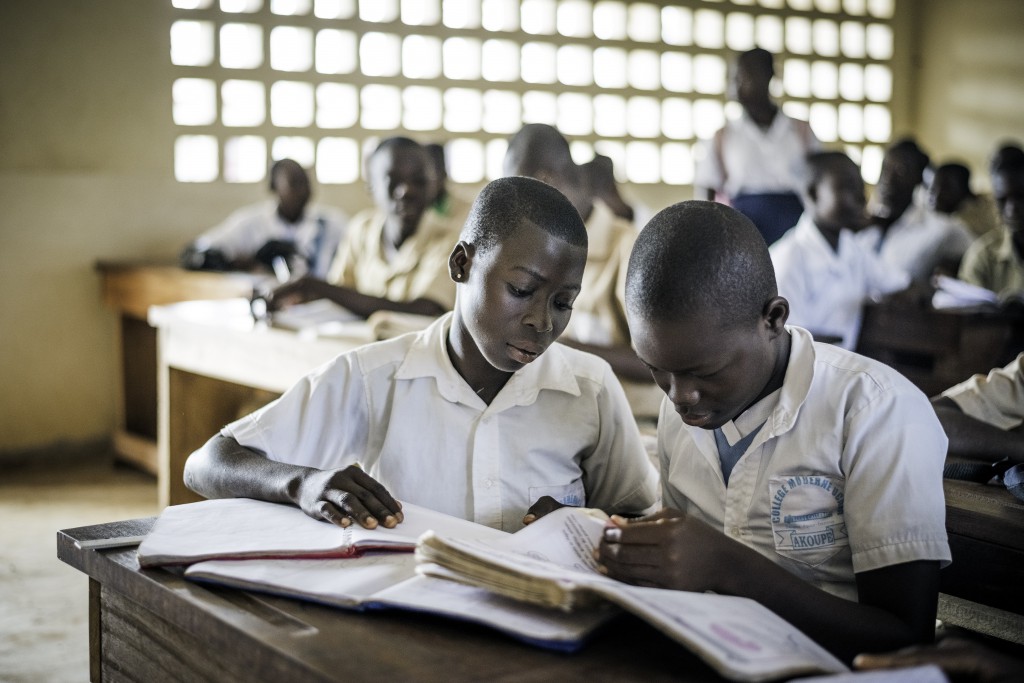

Ivory Coast: to improve young people’s living conditions, the Jacobs Foundation is funding integrated projects to benefit selected rural communities, particularly in West Africa.

You have programmes in Latin America and Africa. How do you carry out your work there? Do you have your own in-country staff or do you work through partner organizations?

We look at how we can best achieve our goals, so we don’t have a rigid model that we always follow. In general, we are small – our companies are also run with very lean management – so we prefer to partner up with strong operational partners for the implementation of our projects, but we have a pretty tight system of control so that we can see what’s going on on the ground. However, if we feel that we can’t find the right partner and, at the same time, that we have the necessary experience and competence, we sometimes assume operational responsibility for project implementation – I must admit that this has not yet happened in Africa or Latin America, but in Switzerland it sometimes has.

In general, is the foundation grantmaking or operational?

We do both. We work with a hybrid model and decide in each case how to proceed. Being a small organization doesn’t mean that we necessarily lean towards grantmaking. Coming from an entrepreneurial background, there are lots of companies that are very successful and still run by a few people; even a small bunch of people can be very successful in operating.

Coming on to the foundation’s assets, do you do impact investing? Or do you have a socially responsible investing policy?

We don’t do impact investing in the strict sense of that term – though of course we measure our impact. However, we do feel that impact investing offers a very good chance to convey to the larger public what not-for-profit investments can achieve and to show that private investments are sometimes more effective than state investments. Not that we think private foundations should replace the state, but private investments can give the chance to show that with new insights or new approaches to certain issues the same goals can be achieved with a better cost-benefit ratio. And that is something we discuss in the management of the foundation.

If you found that major investments in African companies or social enterprises would help further your goals – perhaps with a mixed financial and social return – is that something you’d consider?

Yes. But what we’d rather do is not invest in businesses in our target areas ourselves but rather get businesses to team up with us and invest in businesses while we focus on the social development side. So, taking the proposed investment in Africa, we want companies to invest in the income increase part while we invest in the community development part, where we have the best capability to monitor effects.

The Jacobs Foundation is now 25 years old. Do you envisage any big shifts in direction or emphasis as you embark on the next 25 years?

I think in the past 25 years we have grown up as a foundation and we have successfully introduced a professional approach to improving living conditions using an evidence-based approach. What we have not systematically done so far is looked at scaling up our activities because we feel that we want to get the right management, the right processes in place, good partners and so on first. That’s why scaling up mechanisms will now be in the focus of the next mid-term plan, which runs from 2015 to 2020.

What would you most like to achieve as a foundation?

I’d like to convince decision-makers that increased investment in quality-oriented and evidence-based child development pays off, for the individual, for the economy, for business and for society. There are too few people in the world lobbying for such investments, so we’ve set out our motto, ‘Our promise to youth’, because we feel that we have the market reach, if you want to call it that, to take on that task of lobbying. Youth is the future of society and too few people take that into account.

Do you have any programmes elsewhere in Europe? I’m thinking of places like Spain and Greece where youth unemployment is absolutely massive and must be the biggest social problem.

It’s a very good point. If you look at our annual reports, we targeted youth unemployment over and over again until we shifted our priorities to early childhood development. Funnily enough, I probably caused that shift by asking, ‘where is the most promising return on investment?’ and we realized that it was in early childhood education, and particularly ensuring quality in early childhood education.

We also shifted from investing money in various Western European countries to primarily focusing on Switzerland because we realized that we could have the biggest impact if we focused on a whole country – but only if we knew that country very well. Before, when we invested in different European countries, the risk of failure was quite high because we felt that we didn’t have enough knowledge to address the country-specific critical success factors.

Baden, Switzerland: the Jacobs Foundation is concentrating most of its efforts related to early childhood education on Germany and Switzerland.

Coming back to youth unemployment in Southern Europe, I’m sure we would have taken a different approach ten years ago – for instance, we might have considered specific programmes at Jacobs University for young academics or youths from Southern Europe. You’re right that this is a really relevant issue for Europe, it’s just that it came up after 2008 and we had already shifted our investments into early childhood development.

What about your programmes in Latin America and Africa – they’re surely not focused on early childhood?

No they aren’t. Essentially, in Latin America we are looking at education in life skills, which takes place at school. However, we realized that, when they leave school, children fall into a big hole. What is really lacking in Latin America is an institutional road to employment based on life skills education. So we have launched what we call the Fortaleza programme, supporting six partners in Argentina, Brazil and Colombia, which combines both a specific approach to life skills education and creation of employment opportunities in close cooperation with the private sector.

With the Livelihood programme in West Africa, we’ve learned that addressing gender issues immediately affects early childhood issues. So we don’t directly intervene in early childhood development, but what we do has a secondary effect on early childhood.

Christian Jacobs is chair of the Jacobs Foundation. His younger sister Lavinia Jacobs will succeed him as chair on 1 April 2015.

Lead image: Christian Jacobs (left) with 2014 research prize recipient Michael J Meaney.

Comments (0)