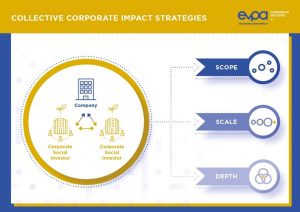

How companies and corporate social investors can deepen, scale or broaden their collective impact.

Philanthropists and impact investors play a major role in driving systemic change and cross-sector collaborations for a more sustainable positive impact on people and planet. However, there is a promising avenue that most of them probably have yet to explore: collective corporate impact strategies.

Over the last decade, philanthropists and impact investors across the world have increasingly started to prioritise systems change. As societal challenges persist – despite individual efforts – the notion to address underlying root causes of societal problems, together with a wide range of stakeholders, has become a more common aspiration, recognising cross-sector partnerships as a vital component of a systemic approach. Such partnerships can bring diverse resources, different types of capital, complementary views, and expertise together to develop interventions that can sustainably address societal challenges.

Not surprisingly, companies have been identified as a potential lever to expand and sustain societal impact. In this context, a growing number of foundations are looking for opportunities to engage and mobilise corporate assets. While many corporate foundations have traditionally kept corporate philanthropy clearly separate from the company, around 70 per cent of foundations[1] are now seeking strategic alignment with their related company. Corporate foundations and other corporate social investors (e.g. corporate impact funds, corporate social accelerators) have realised that by aligning on themes or societal challenges that also relate to the business, they can utilise corporate resources more strategically for their own impact, while also sending positive impulses about social investment opportunities to the company.

Yet, to truly move towards more holistic and lasting impact strategies, such bilateral partnerships have their limitations. One limitation is that corporate foundations are often restricted by law or by their mission scope from working closely with their founding company, placing their charitable status and credibility at risk. Another limit is that some foundations can only issue grants, while other financial instruments, like debt and equity, might be more appropriate to create scalable social impact. On the other hand, companies are often restricted to financial investments that yield a certain financial return. If corporate foundations and companies really want to move towards more holistic approaches, they need to find new ways to bridge the philanthropic work of a foundation and the commercial interest of a company.

Overview of the Collective Corporate Impact Strategies. For more information, visit evpa.eu.com.

Some progressive companies and corporate foundations have therefore started to set up new organisations, like impact funds, accelerators, or corporate social businesses that can complement their work, combining social impact with financial objectives. Repsol Foundation for instance launched a new impact fund in 2019. Ikea set up IKEA Social Entrepreneurship alongside IKEA Foundation, and Vodafone does not only have 27 national foundations, but also founded a European think-tank, the Vodafone Institute for Society and Communications.

By setting up multiple impact structures and aligning them on a common vision, the organisations are moving towards more holistic impact strategies to either broaden their impact on society, scale the impact of promising societal solutions, or deepen their impact on a particular community. In the following, we will explain each approach in detail.

Depth

Companies and corporate foundations can set up an additional vehicle to deepen their impact on particular communities. In these cases, they recognise that if they want to generate long-lasting change for their beneficiaries, they need to address interrelated challenges at the same time. A new impact structure can then be established with an impact strategy that complements the foundation and the company’s work to address a particular societal challenge.

Schneider Electric for instance has a vision to provide energy access to all. Yet, as Emilienne Lepoutre, Access to Energy Strategy and Performance Lead at Schneider Electric, shared with us: ‘We realised that if we want people in South East Asia or in Sub-Saharan Africa to be able to utilise energy access for development, only providing energy technologies is not sufficient. We will need technology, plus skills, plus investment capacity. We need to have a holistic view of the challenges and a holistic response’.

The company therefore has a foundation providing vocational training in electricity to foster local job creation, while Schneider Electric Energy Access fund supports early and growth stage ventures providing new energy access solutions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Acknowledging different geographical needs, Schneider Electric also set up a separate impact fund specifically for South and Southeast Asia, predominantly focusing on the productive use of energy.

While many corporate foundations have traditionally kept corporate philanthropy clearly separate from the company, around 70 per cent of foundations are now seeking strategic alignment with their related company.

The benefit of this collective approach is that the different organisations can respond to different local needs related to a particular challenge. For instance, while Schneider Electric provides the technology to install a new micro grid in rural areas, the foundation can help train people locally to install and maintain the grid, making sure the technology yields sustainable access to energy, while creating local job opportunities. Covering a wide range of complementary solutions (from impact-driven to commercially-driven) and investee organisations (from NGOs to social enterprises or for profit organisations) can help the organisations instigate more profound and lasting change for the communities. At the same time, bringing together different areas of expertise around a particular community, sharing experiences, and learning from each other can also help identify levers for systemic change.

Scale

The second opportunity for companies and corporate foundations to set up a new corporate impact structure is to scale promising societal solutions and innovations from incubation to maturity. A common challenge is that early-stage social enterprises often struggle to find appropriate funding during the so-called ‘valley of death’ or ‘missing middle’, when they are no longer eligible for the philanthropic support of a foundation but are still too risky for companies or traditional investors to invest in. By setting up a complementary impact fund or social business that can cover the gap between the foundation’s and the company’s support, the organisations can ensure that social enterprises receive the necessary support to prosper and scale.

For example, Rabo Foundation has been supporting early-stage farmer cooperatives and other farmer-based organisations in developing countries. As the cooperatives and social enterprises successfully grow and professionalise, they eventually reach a stage where they outgrow the philanthropic support of the foundation. However, the organisations are then typically still too financially vulnerable and risky to receive follow-on funding from commercial lenders. The foundation therefore established the Rabo Rural Fund, an impact fund that can offer cooperatives and farmer-based organisations follow-on capital, such as loans and equity, to cover this missing middle. Once the cooperatives are attractive for commercial banks, either Rabobank, a global food and agri bank, or other local partner banks can then provide the next phase of funding and help these organisations scale their operations and impact on smallholder farmers in developing countries.

The benefit of such a collective approach is that the different impact structures can respond to the changing needs of social enterprises and innovations as they transition through different development stages. For instance, a foundation can support social enterprises at their early development stages through patient grant-making capital, while an impact fund can use other financial instruments like debt or equity to help them scale and become more attractive to follow-on investors. This system helps create an environment that supports social enterprises and innovation to reach maturity. By working together with the company, the foundation and the impact fund can also pave the way for scaling through either the company’s value chain or their business partners. For example, Rabo Foundation and Rabo Rural Fund have been able to connect farmer cooperatives with clients of the bank that were interested in sourcing their agricultural products, allowing the cooperatives to scale their operations and have a bigger impact on the farmers’ livelihood and self-reliance.

Scope

The third opportunity for companies and corporate foundations to set up an additional corporate impact structure is to broaden the scope of their impact on society. These organisations realise that there are diverging societal challenges, geographical areas, or stakeholders that are important to focus on in order to build a healthy ecosystem. By setting up a new impact structure with a new scope, companies and corporate foundations can expand their impact into such areas.

Vodafone for example thrives to build a digital society that enhances sustainable, socio-economic progress for everyone. While the company pursues this vision by developing new technologies to connect people and organisations, they also recognise that their vision transcends the impact of their own business. To make a digital future accessible to particularly the more vulnerable people, Vodafone therefore supports 27 local corporate foundations. The Vodafone Germany Foundation for example runs programmes to advance digital skills of pupils, such as the coding for tomorrow initiative which teaches children essential coding skills for the digital workforce. At the same time, new societal challenges related to the digital transformation, such as how to use new technologies in a responsible way, or how artificial intelligence solutions can be implemented ethically, were becoming more relevant, yet were beyond the mandate of the foundations. The company therefore decided to set up a complementary a European think tank on digital technologies and their responsible use for innovation, growth, and sustainable social impact, the Vodafone Institute. The institute not only drives research, but also aims to connect and inform thought leaders from science, business, and politics. As part of their collective efforts, each organisation contributes to the same vision of a sustainable and inclusive digital society, while each focuses on a different angle.

If corporate foundations and companies really want to move towards more holistic approaches, they need to find new ways to bridge the philanthropic work of a foundation and the commercial interest of a company.

The benefit of this collective approach is that it enables the organisations to respond to diverging societal needs, such as advancing digital education for children, while also advising politics, business, and scientists on the ethical and sustainable use of digital transformation. This approach also allows the organisation to expand their geographic coverage, i.e. the foundations can focus on local needs while the institute can focus on the broader European level. Lastly, it allows for a more agile response to external and internal changes. With the global health crisis, the Vodafone Institute launched studies about how digital technology can be used to fight Covid-19 in an equitable and sustainable manner. If they had not set up the institute, they may not have been able to contribute to such emerging needs. Using this collective approach, the organisations therefore acknowledge that social progress is multifaceted and that they are willing to advance progress in various areas.

Relevant for society and business

Philanthropists and impact investors are important actors in driving systemic change and cross-sector collaborations for more sustainable impact at scale. With this novel approach of developing collective corporate impact strategies, corporate foundations and other (corporate) social investors can combine different financial instruments, from grants to loans and equity, and areas of expertise, from incubating social innovation to building scalable business models, to develop more holistic and systemic strategies for societal change.

At the same time, this approach can also help companies elevate their sustainable and inclusive business strategy. Working collectively with a foundation and other corporate social investors, companies can for instance stay abreast about new social innovations emerging in the social sector, while using their insights about the needs of low-income communities to develop more relevant inclusive and sustainable business practices. This new approach can also accelerate the development of pre-commercial markets, by slowly changing the socio-economic conditions within particular communities. Lastly, as foundations, impact funds or other corporate social investors help social enterprises develop robust business models, this approach can also be a great opportunity for all companies looking for scalable societal solutions. Thus, collective corporate impact strategies are not only important for society but can also be relevant to businesses looking to push the boundaries on their sustainability and inclusive business strategy further ahead.

Karoline Heitmann is corporate initiative manager at the European Venture Philanthropy Association (EVPA). Lonneke Roza is community investment manager international at NN Group, responsible for the implementation of the community investment strategy across NN Group. While writing this article, she was collaborating with the EVPA Corporate Initiative. Alessia Gianoncelli is head of the knowledge centre at EVPA. Steven Serneels is chair of EVPA and EVPA’s Corporate Initiative.

The authors would like to thank Nicolas Malmendier, Corporate Initiative Associate, and Sophie Faujour, Corporate Initiative Lead at EVPA for their valuable contributions to the research.

Alliance magazine is pleased to offer free access to this article thanks to EVPA.

Alliance magazine is pleased to offer free access to this article thanks to EVPA.

Footnotes

- ^ Statistics based on a polling with 76 corporate foundations and other corporate social investors in 2019

Comments (0)