Johannesburg, South Africa

What do a British-based minerals company, French-based energy company, Dutch-based homeware company and Belgian-based beverage company have in common?

First, they are multinational corporations (MNCs) operating in Africa who have been implicated in controversies to do with Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) and tax avoidance – with potentially significant revenue loss for the host African countries. Second, each has a significant, and sometimes much lauded, philanthropy connection, which brings their tax practices into focus.

For the African continent, the issue of tax justice has become increasingly significant. Long seen as a development begging bowl, the continent is actually a net creditor to the world.

For the African continent, the issue of tax justice has become increasingly significant. Long seen as a development begging bowl, the continent is actually a net creditor to the world.

In 2015, Sub-Saharan Africa received $19.7 billion in official aid and $11.8 billion in private grants. In that same period, however, ‘$68billion was estimated to be lost through capital flight, mainly by multinational companies deliberately misreporting the value of their imports or exports to reduce tax.’

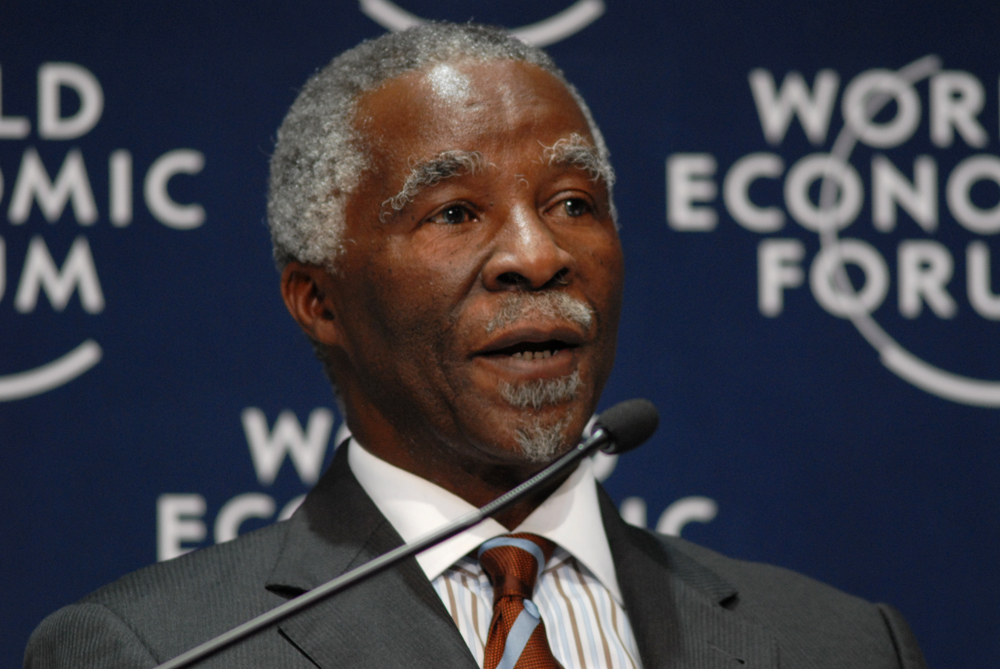

In 2016, Thabo Mbeki, the Chair of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, announced that the panel had revised its original estimate.

The continent was losing between $80 billion and $90 billion per year to IFFs. In a context where transactions are shrouded in secrecy, and where, much still remains uncovered, despite investigative efforts, even these figures are likely to be conservative.

…and it’s legal!

While criminal activities such as tax evasion, corruption and trafficking are often the focus of attention, tax avoidance which uses legal means to maximize profits actually accounts for the bulk of outflows.

The four stories below illustrate how these illicit flows work:

1.) A multimillion-dollar MNC subsidiary in Ghana showed sales of £63.3 million between 2007 and 2010, yet managed to make a pre-tax loss of £3.7 million.

Its tax bill over the four-year period was a mere £216,000 pounds and for three of the four years it paid no tax at all. How is this possible? By using royalty payments to its Dutch parent company (which has minimal tax on royalties received), allocation of management fees to sister companies in tax havens, routing of goods via shell companies in tax havens and borrowing money from its subsidiaries in low tax jurisdictions.

Its tax practices have resulted in a loss of close to £20 million in tax revenue to different host countries in Africa and to India. Yet this same MNC is much lauded for its CSR programmes and is often cited as an example of innovative practice in the field.

2.) A MNC operates in Niger, one of the least developed countries in Africa. Despite contributing 30 per cent of the MNC’s uranium requirements, it only receives 7 per cent of the payments the MNC makes to uranium producing countries.

Downward manipulation of the internal price of uranium extraction and under-invoicing its export cost of uranium (sold to the parent company in France) has meant that royalty and tax payments were between €11 to 30 million less than they should have been in 2015.

That amount could cover between 8 and 18 per cent of Niger’s health budget.

This MNC provides funding through both corporate social responsibility initiatives and a foundation, and has funding partnerships with the Nigerien government and the Global Fund to Fight Aids Tuberculosis and Malaria.

3.) A MNC operating in Southern Africa is estimated to have undervalued the export price of its minerals by over $2.7 billion over an eight-year period, thus effectively setting its own tax rate.

It has also over-valued minerals imported from affiliated companies in order to reduce its tax liability. At the time, this MNC was headed by someone who is a renowned and respected philanthropist, who has established more than one prominent and well-endowed foundation.

4.) A home goods MNC operating in 44 countries is accused of avoiding over €1 billion over a six-year period, primarily through paying royalties, interest and other charges to its subsidiaries and sister companies in tax havens.

With €26bn of sales in a year, it is reported to have paid 33 times less tax than its nearest rivals. This is possible because, in addition to the illicit transfers, the MNC is ultimately owned by a foundation – one which has spent only a minute amount of its assets, and is thus seen by many as merely a tax shelter.

These examples illustrate the legal but aggressive tax planning strategies used by MNCs. There are many others, for example, even less visible mechanisms like tax holidays, tax deferment and preferential pricing agreements are demanded, or offered as incentives, at significant cost to developing countries.

The HSBC, #PanamaPapers and #ParadisePapers leaks have finally placed a spotlight on these issues and highlighted the morally questionable practices of offshore accounts and tax havens. The philanthropy media is also starting to pose some awkward questions for philanthropy about their offshore investments.

The tax elephant in the philanthropic room

But tax is an unpopular topic for most; in philanthropy, even more so. It often sits in the shadowy corner of our discussions, brought up vigorously when advocating for an incentivizing climate for charitable giving, but uncomfortably bypassed when questions of tax justice, accountability and the movement of money are raised.

Rarely have we had balanced and critical discussions exploring the range of positive and negative links between the philanthropy sector and the broader tax environments within which it operates – and the contradictions that emerge from these.

These are difficult conversations. Big philanthropy in particular – High Net Worth philanthropy, large corporate and private foundations – are a direct product of the inequitable economic systems that currently dominate.

Most of these large philanthropic institutions have made their money or are currently doing so, in a system that prioritizes profit maximization; and an important element of that profit maximization is tax planning – which becomes problematic when shrouded in secrecy and resource flows are hidden.

When foundations invest in companies which have aggressive tax planning components, generate resources through parent corporations that engage in transfer pricing, exploit the secrecy of traditional tax havens like Bahamas as well as lesser known jurisdictions such as Delaware or the City of London or employ creative use of philanthropic mechanisms to mask business objectives – we, as a sector, are directly or indirectly complicit – even more so by our limited efforts to tackle these questions head on.

When foundations invest in companies which have aggressive tax planning components, generate resources through parent corporations that engage in transfer pricing, exploit the secrecy of traditional tax havens like Bahamas as well as lesser known jurisdictions such as Delaware or the City of London or employ creative use of philanthropic mechanisms to mask business objectives – we, as a sector, are directly or indirectly complicit – even more so by our limited efforts to tackle these questions head on.

Why have we turned a blind eye?

Embedded in this is the philanthropic sector’s ambivalent approach to its own accountability. There is an argument which says that since most money is tainted in one way or another, questioning the source of philanthropic funds is a non-starter. As a sector we should thus be focusing on increasing philanthropy – and balance that against the good work that emerges.

This argument fails to acknowledge that the harm caused by unethical business practices that resource philanthropy often far outstrips any philanthropic dollars spent. Another argument is that philanthropic money is private money.

‘There is another argument which says that questions of how philanthropic money is made is being unfairly focused on emerging philanthropy…’

How it is made or used is private business and should not be a matter of public discussion. Yet, the fact that philanthropic institutions – in many parts of the world, particularly the global north – are tax-exempt (thus decreasing funds from public budgets), should mean that there is public scrutiny and accountability.

There is another argument which says that questions of how philanthropic money is made is being unfairly focused on emerging philanthropy – which is predominantly in the global south – and that long-standing philanthropic institutions in the north, for many of whom, the stain of unethical resource accumulation has faded with time, are escaping scrutiny.

Hence, there is a double standard operating, which sets the bar higher for emerging philanthropy. If this is so, it is inadmissible. Scrutiny over current resource acquisition practices cannot be ignored simply because it has been so in the past.

At the very least, do no harm

Some say that philanthropy is already making significant strides in accountability – and cite measures to elicit grantee feedback, or which make, say, the distribution of their funding partners and the amounts transparent while recognizing that secrecy is sometimes needed to protect funding partners against authoritarian regimes. In a field where privacy has been well guarded, these are important steps, but only go part way towards accountability.

True accountability must be based on the commitment to do no harm. Philanthropic resources bolstered by tax practices that further entrench systematic inequality are not innocent and should make all of us reflect on the business we’re in.

The issues related to philanthropy and tax could also damage our sector’s ability to counter increasingly insular and conservative governments threatening the civic space and philanthropic freedom. Without adequate knowledge of where the philanthropy-tax intersections lie, the sector could find itself blindsided by restrictive regulations.

Moreover, there is increasing evidence of very legitimate tax incentives being abused/misused for business ends – using the shell of philanthropy as cover. Without transparency and accountability, these will continue. Lastly, as the sector continues to advocate for an enabling/incentivizing regulatory environment for giving, it needs better knowledge of the unintended consequences of the reforms it advocates, as well as potential conflicts with reforms being advocated by the global tax justice movement.

Philanthropy has an important role to play in enabling a more equitable and just society. In recent years, efforts such as the Divest-Invest campaign have started to push philanthropy to be more selective about its investments, and many practice negative screening to avoid investing in sectors like arms, alcohol, tobacco and gambling.

All of these, however, address a particular sector of industry. There are no initiatives that question the business practices of those that philanthropy invests in or derives it funds from.

The argument here is not that philanthropy is necessarily deliberately complicit, but that insufficient exploration of the intersection points between philanthropy and inequitable tax practices mean that philanthropy – by omission – can potentially do as much harm as it does good.

Though several steps removed, very few large philanthropic institutions are without a connection to IFFs.

While some of these connections may be known, many may not be as these resource governance questions are rarely asked.

It is past time for philanthropy to look at itself, acknowledge the contradictions at work, improve its resource governance and, significantly increase funding to those organizations and movements tackling the issue of tax justice head on.

Alliance Philanthropy Thinker: Halima Mahomed

Halima Mahomed is an independent consultant whose work focuses on research and advocacy to strengthen the narrative, knowledge, practice and impact of African philanthropy. Over the last 16 years she has been closely affiliated with, amongst others, the Ford Foundation, TrustAfrica and the Global Fund for Community Foundations. She is also a member of Philanthropy for Social Justice and Peace and of the Alliance Magazine Editorial Board. Halima has written extensively on African philanthropy, and holds a Masters in Development Studies, with a focus on social justice philanthropy.

Halima Mahomed is an independent consultant whose work focuses on research and advocacy to strengthen the narrative, knowledge, practice and impact of African philanthropy. Over the last 16 years she has been closely affiliated with, amongst others, the Ford Foundation, TrustAfrica and the Global Fund for Community Foundations. She is also a member of Philanthropy for Social Justice and Peace and of the Alliance Magazine Editorial Board. Halima has written extensively on African philanthropy, and holds a Masters in Development Studies, with a focus on social justice philanthropy.

Visit The Philanthropy Thinker for more content from the series.

Comments (2)

Thank you so much for this article Halima! Such an important perspective and so taboo still in the philanthropy world.

This is a thoughtful contribution to an important debate. The ambivalence of the philanthropic sector on this issue is worrying. Time for some of philanthropy’s umbrella organisations to focus on our murky relationship with tax....?