Organized philanthropy exists because a few individuals are able to accumulate a vast surplus of resources. Given how much good is done with philanthropic donations, it seems ungrateful to look too closely at the source of that money. Yet recent financial data leaks, including the Panama Papers and the earlier HSBC Swiss Files, act like glasses for the myopic—they bring into focus one of the wealth management practices that enables private individuals to hold on to resources. Moreover, a number of named individuals are well-known philanthropic donors. With these revelations, the sector should look hard at the uncomfortable ways in which some of our most respected institutions and advocates may be complicit in questionable practices.

Investigations into the Panama Papers and the Swiss Files are still ongoing, but have to date listed members of the donor community. The finance billionaire and philanthropist George Soros, founder of the Open Society Foundations, owns three offshore companies.

UK resident David Potter, co-founder of the David and Elaine Potter Foundation, appeared in the HSBC Swiss Files as holding approximately £70 million in bank accounts in Switzerland, and paying little to no UK tax on other assets due in part to UK “non-domicile” exemptions offered to wealthy non-citizens living in the UK (Potter is South African).

Human rights funder Sigrid Rausing, founder of the Sigrid Rausing Trust and a UK resident, similarly owns Swiss accounts and benefits from “non-dom” status as a Swedish national.

These respected names join a growing list of the world’s wealthy, including US President-elect Donald Trump, U2 front man Bono, and football star Lionel Messi, all of whom have been suspected of holding on to a large share of their wealth through questionable tactics, and who are founders or major donors to philanthropic organizations.

Such opposing behaviors seem confounding. Why go to such lengths to avoid paying taxes on funds that will just be given away? What view, if any, should the philanthropic sector take on the sources and management of its funds given its location at the intersection of private wealth and public benefit?

| What are the Panama Papers and the Swiss Files? |

|---|

| The Panama Papers are a stash of 11.5 million records hacked from the records of Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, a provider of specialist financial services to wealthy individuals who want to establish an offshore bank account, trust, or business. An anonymous hacker gave the Panama Papers to Suddeutsche Zeitung journalists Bastian Obermayer and colleague Frederik Obermaier, who then shared the leaked files with the International Center for Investigative Journalism (ICIJ). The ICIJ is the current steward of the files for both the Panama Papers and the HSBC Swiss Files, an earlier leak of documents held by the Swiss arm of HSBC, and captured by whistleblower IT employee Herve Faciani. The Swiss Files revealed how HSBC actively helped clients hide funds in order to avoid paying taxes on them. Together, the files reveal a web of countries, international financial institutions, law firms, accountants, and individual citizens using offshore instruments. Well-known financial institutions such as Citi, Chase Private Bank, Deutsche Bank, ING, and others acted as intermediaries on behalf of wealth holders, and private companies, law firms and accountants worked together to keep the identity of the beneficial owners secret. |

Why go to the trouble?

Few would question the morality and legality of minimizing taxes through choices in spending and investment. That is in fact a purpose of tax policy—to encourage citizens to make choices that benefit them, while discouraging choices that do damage. Saving for retirement or starting a business are subsidized through tax write-offs; smoking is discouraged with a tax charge. There is nothing wrong or illegal about maximizing the positive, just as there is nothing inherently wrong with forming an offshore entity.

But one of the defining muddles of the Panama and Swiss Papers is that the difference between legal and illegal, legitimate and shady is difficult to parse. The offshore world appeals to many exactly because the ultimate beneficial owner of an account, trust, or company is hidden behind the banks, law firms, accountants, and third-party ‘agents’ paid to sign the papers. The whole system operates with owners who don’t benefit, and beneficiaries who do not appear to own.

But it would be wrong to assume that everyone who sets up an offshore account has something to hide. Secrecy is also privacy and there are sometimes good reasons to remain private. Some want privacy because they don’t want to call attention to themselves, others for reasons of personal safety. Philanthropy has long allowed the identities of donors to remain anonymous as a way to protect them.

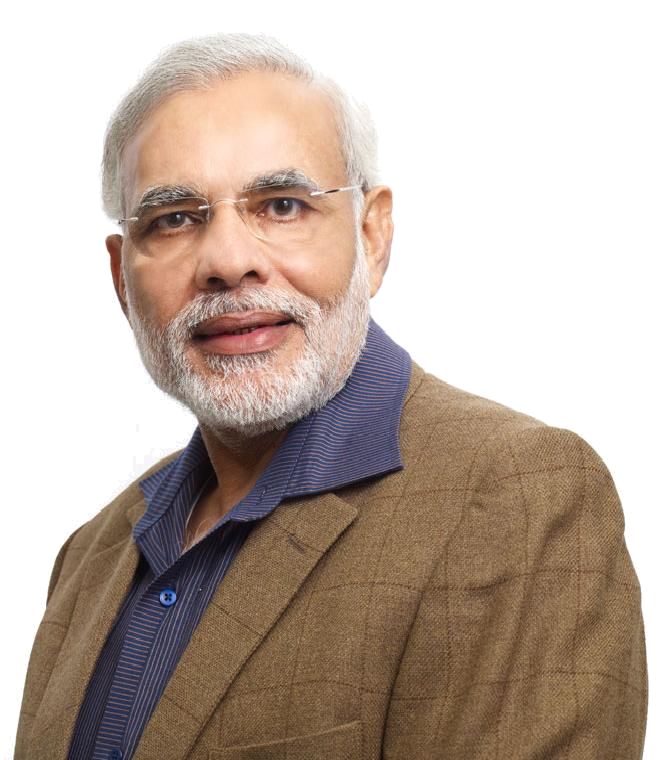

It was not so long ago that being a member of a local workers’ association in the United States tagged one as a communist, an honorarium that could get that person fired, arrested, even mobbed. Those same dangers have been faced more recently by activists of the Arab Spring, by dissidents in Russia, or LGBT community members in Kenya. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is engaged in efforts to defund and delegitimize a huge number of civil society organizations. Staying private is sometimes a real imperative.

Secrecy, in short, is not an inherent problem, but the de facto nature and huge scale of these secret operations in the offshore world is. Legal or not, offshore entities are one link in a systemic chain that allows people of wealth to pay less than their share in tax. This loss of tax revenue has economic implications for people at all levels of the socio-economic spectrum and the numbers involved are significant.

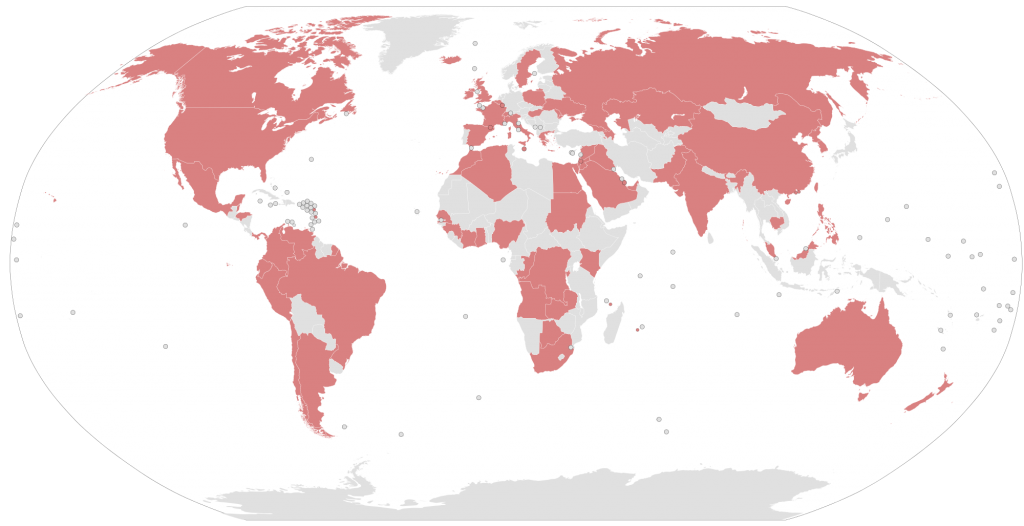

The UC Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman, author of Wealth of Nations, writes that at least 8 percent of the world’s wealth is “missing,” or outside of the transparent parts of the financial system, totalling between $7.6 trillion and $21 trillion in total resources. Zucman estimates that developed economies lose a collective $200 billion in taxes annually because of such “hidden” wealth. Not all wealthy donors participate in hiding wealth, but they do benefit from the systems that allow it and which include myriad ways to limit tax and other obligations.

From that perspective donors avoid paying taxes on funds they intend to give away because the wealth managers and accountants they rely on to manage their wealth have a professional mandate to maintain and maximize resources. That’s what they do, and they do it well. The effective tax rate paid by high-income individuals is sometimes lower than the one paid by middle or low-income households, even without the use of offshore instruments.

This intellectual inconsistency of donors is mirrored in other conflicts throughout the philanthropic world. Consider the ongoing tension between a foundation’s mission and grantmaking on the one hand and how its corpus is invested on the other. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has been criticized for holding investments in companies whose business practices are in direct conflict with the foundation’s mission. These conflicts may end up with the balance of good works exceeding the negative. Yet such conflicts occur because of the wall that organizations erect between their grant-making and fund-management arms. Some foundation leaders such as the Heron Foundation’s Clara Miller have argued that it’s time to tear down these walls.

This is not to say that givers are passive beneficiaries of the wealth creation system. The second reason why wealthy donors may avoid taxes is that trust in public systems is low, and they see government as wasteful or as spending in ways that do not reflect their priorities.

US President-elect Donald Trump captured this sentiment in a post-debate comment when he said to a CNN reporter, “I hate the way our government spends our taxes because they are wasting our money. They don’t know what they’re doing.” Such sentiment echoes with the 1980s refrain “Starve the Beast,” coined during the Reagan era as a political slogan that advocates lowering taxes as a way to force cuts to public programs.

Since taxpayers don’t in reality get to choose where the money goes, wealth holders may feel justified in the actions they take to choose through the means available to them. It is common today for the famous and infamous to invest both their celebrity and their resources in causes that their governments either do not prioritize, or pursue with policies that they don’t agree with.

Bono, for example, has used his worldwide rock stardom to advocate for debt forgiveness for developing economies, and to raise money for his nonprofit organizations. Yet on the other side of his personal ledger, he and his bandmates have moved their business to the Netherlands, and he has used offshore mechanisms to avoid Irish tax. He has claimed that such actions make him a smart businessman, while in the same breath criticizing government lenders for requiring borrowers to honour their debts.

The danger of biased interpretation

There is danger in taking a different position on these realities depending on who is using them and for what purpose. A tax avoider who donates millions in diapers, clean water, and clothing for Syrian refugees may be waved through the check point of public opinion, whereas someone who donates millions to the National Rifle Association gets stopped. Or vice-versa.

Such intellectual bias may be unavoidable. Some have already criticized the Panama Papers investigations as reflecting left-leaning bias by focusing on named political figures and ignoring progressive business figures like Soros, whose Open Society Foundation supports the ICIJ and other efforts around the world to promote transparency.

The role of secrecy is particularly problematic given how important secret systems are for privacy purposes. One of the major findings from the Panama Papers revealed the influence foreign money filtered through offshore companies has had on real estate in world capitals.

Azerbaijan’s first family, the grandson of the Kazakh president, the daughter of Pakistani president Nawaz Sharif, as well as Mr. Potter, are known owners of London real estate purchased through offshore companies. Such secret and anonymous purchases distort real estate prices, as properties are bought and sold by anonymous dealers hidden from the public market.

Moreover, these transactions take money away from public budgets and welfare programmes. Offshore owners cannot be forced to pay taxes on the appreciated value in the event of a sale. Parents that pass holdings to their children through shell firms can do so without subjecting the latter to inheritance tax.

Yet there are also valid reasons why a property owner would want to remain anonymous. Consider a recent episode in the United States involving Ta-Nehisi Coates, a prominent black writer and social critic. Coates and his wife set up a limited liability corporation through which they anonymously purchased a house in Brooklyn. This is a common and legal tactic used in New York real estate to protect the identity of buyers. Coates went to such lengths because he didn’t want his address to be public knowledge, a not-outrageous desire for a man outspoken about systemic racism in the US. Despite these efforts, someone leaked the property purchase information to a New York newspaper, which published an article with Coates’ name and new address. The couple, who have a young son, put the house back on the market.

There is a strong instinct to say that Coates should be allowed his privacy, but the grandson of the Kazakh president should not. Yet both are using techniques and systems to safeguard privacy albeit in different ways and for different reasons. Legal changes that deny the grandson access to these systems could deny everyone—including people who want to use them to allay real concerns about privacy.

The financial industry and its regulations will need to solve some of these problems, but finance companies cannot do it all. Regulations designed to prevent money laundering or illegal use of offshore accounts—such as ‘Know Your Client‘, as an example—go part way to solving some of these issues and could be enhanced. The banks, law firms, and wealth managers serving wealthy clients are responsible for fulfilling the regulations, and mostly do so.

But there will always be instances when officials either don’t see, or fail to sound the alarm when a client tries to use the financial system for questionable or corrupt purposes. Correspondence between Mossack Fonseca employees and private banks, as well as between HSBC representatives and wealthy clients provide ample evidence of players on all sides actively choosing to look the other way when confronted with clear intent to defraud.

Should the philanthropic sector care?

These issues are coming up at a time when society is deeply divided about nearly everything, and this divisiveness hinges decisively, though in confounding ways, on money.

The Brexit vote, the election of Donald Trump to the US Presidency, and the contentious election underway in France are all grounded in the feeling, widespread across Western democracies, that the primary sources of 21st century wealth creation—including global trade, technological advancement, and new tools available in the financial system—benefit very few and cost many. They leave huge percentages of the population underserved, forgotten, and left behind.

Western societies made a bargain over a century ago that governments will not get everything right, and that society as a whole is better off leaving some social resources in the hands of private institutions including philanthropy.

But with that bargain comes the implicit expectation that those institutions and the individuals that fund them remain at some level accountable. Arguably we aren’t pushing hard enough to fulfill those expectations of accountability. As a philanthropic sector, we are still too willing to look away when our most generous donors are associated with systems which are unseemly, opaque and sometimes used for corrupt purposes.

The philanthropic sector in general has a lot of progress to make in meeting standards of accountability. Foundations continue to be some of the least accountable actors in democratic society. When those same institutions also benefit from offshoring—whether through donors that leverage offshore entities, or through offshore investment practices—they damage their integrity and credibility as institutions living up to the promise of the sector to act in the service of humanity.

If philanthropic organizations want society to be more fair and accountable, than philanthropy has to start at home—be the change you seek. It should be standard practice for foundations to publicize financial investment strategies and explain their rationale. If a foundation holds or invests assets offshore, it should explain why. The financial conflicts that arise today are not simple nor simply solved. The philanthropic sector is not exempt from these conflicts. Instead it should confront them head on. A re-doubling of the commitment to transparency provides a useful place to start.

Laura Starita is co-founder and managing partner of Sona Partners.

Timothy Ogden is executive partner of Sona Partners, is part of the board for GiveWell, and is a contributing editor to Alliance.

Comments (0)

Great news for us.