Two stories of philanthropy in the 1940s and 1950s show how the effects of funding can reverberate down the years.

Two women studying at the Business School of Texas Southern University in 1966. Credit: Marc St. Gil

In writing for our online storytelling platform, RE:source, I use the archival records of foundations and not-for-profit organisations to bring to light stories that relate to current concerns. In the case of gender and economic inequality – major societal challenges that philanthropy is currently trying to mitigate – two seemingly disparate stories come to mind.

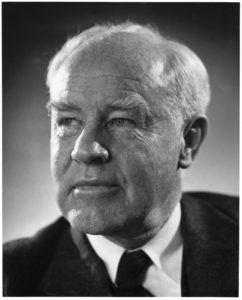

The first is the story about a relatively small philanthropic investment in Alfred Kinsey’s sexuality research in the 1940s and 1950s.

The second, by contrast, is the story of how a staggeringly large amount of funds in the 1950s set out to revolutionise the private sector, professionalising business practice for the greater good.

Kinsey’s work provided important data-driven evidence to the rights movements in its continuing struggle to achieve parity, protection and social justice.

Here’s how they played out.

In the early 1940s, Alfred Kinsey had a revolutionary hypothesis: human sexuality did not fall into strictly binary categories. To test it, he would need funding for a scientific inquiry. But with the Second World War ramping up, and laws criminalising homosexuality on the books, support wasn’t easy to come by. That’s when philanthropy stepped in.

Rockefeller and Kinsey

The Rockefeller Foundation (RF) became the primary financial backer of Kinsey’s research, providing annual funding for the project that by 1947 amounted to $40,000, the equivalent of approximately $500,000 today, which led to the production of the groundbreaking Sexual Behavior in the Human Male in 1948.

He and his co-authors used study data to support the assertion that human sexuality was spread across a spectrum, from exclusively homosexual at one end to exclusively heterosexual at the other. What has since become known as the Kinsey Scale plots the vast majority of human sexual identity somewhere in between.

The book was a commercial success and, as one might suspect, it also ignited heated controversy. If RF’s leadership had regrets about its involvement, however, they did not let on. In fact, the paper trail contains letters from several trustees expressing reassurance and support.

The study’s establishment of non-binary human sexuality as the norm did not lead instantly to social acceptance of the idea, but Kinsey’s work provided important data-driven evidence to the rights movements in its continuing struggle to achieve parity, protection and social justice.

The RF’s grants to Kinsey reveal some lessons. First, its willingness to take a measured risk was instrumental to Kinsey’s success. Funding the sexuality study was not at all a shot in the dark, but sat within the long-established RF funding areas of science and medicine, albeit on the margins. That familiar scientific approach gave foundation leadership the confidence and security to fund the study of what might otherwise have been considered a social and cultural issue.

Second, the extent to which one foundation staff member can make all the difference. RF’s Medical Sciences director, Alan Gregg, was Kinsey’s steadfast advocate within the foundation. But once he was promoted to a vice presidential position and no longer directly oversaw the Kinsey grant, the project lost the strong support that programme-level staff can give.

Third, finding the right exit strategy isn’t easy. Once Kinsey’s book was out, RF leaders argued that royalties would suffice to fund future research. Or perhaps they used commercial success as an excuse to pull grant funding. In any case, they agreed on a three-year tie-off grant to show the foundation still had confidence in the work, to give Kinsey time to raise funds, and to give themselves an exit.

The issues Kinsey and his team raised have had lasting impact. Neither he nor the RF staff sought to fund a social movement, which would have been well beyond the scope of the grants. But the philanthropic staff did not try to stop one from happening, either. In the end, the RF funded behind-the-scenes work that would be taken up by others in revolutionary new ways.

Making ‘economic statesmen’

The Ford Foundation, on the other hand, did have larger social aims and a larger cheque book when it decided to revolutionise business education after the Second World War. Ford leaders committed the foundation to promoting democracy and free markets around the world and its programmes helped create international agencies and fund development work, all contributing to the building of an increasingly interconnected global economy.

Funding the sexuality study was not at all a shot in the dark, but sat within the long-established RF funding areas of science and medicine, albeit on the margins.

However, some in Ford’s upper ranks worried that business and industry leaders back in the US lacked the full range of skills or perspective necessary to weather economic storms. The business sector focused primarily on day-to-day operations, never making plans beyond the next quarter. There was no widely-adopted theory of practice, no broader social view, staffers argued. They also believed that those engaged in business had a civic duty, as leaders in society. The pivotal Ford-funded Gordon and Howell study of business education argued that proper training should create ‘economic statesmen’. In 1954, Ford spearheaded a movement to make American business schools less vocational, more academically rigorous and theoretically grounded.

In just ten years, Ford grants to business education totalled $46.3 million (about $380 million in 2020 figures). These funds created centres of excellence, supported business schools across the US, funded individual faculty fellowships, research and book projects, and workshops to boost the quality of teaching and learning at business schools.

While different from the Kinsey story, the business education episode shows another foundation working within its own wheelhouse. Ford drew on its experience working with American institutions of higher education to completely overhaul business education. However, while the programme was successful in making rigorous business study a prerequisite for private sector leadership, many today call for a second revolution in the field. Where a half-century ago it seemed that free markets and democracy went hand in hand, today there is a growing feeling that the two are often at odds.

Where a half-century ago it seemed that free markets and democracy went hand in hand, today there is a growing feeling that the two are often at odds.

In the decades since the business education revolution, Ford was flexible enough to change course, funding new approaches to combat rising economic inequality and helping to create the programme-related investment to support minority enterprise in 1968.

New orthodoxies and wrong assumptions

Looking at philanthropy’s history, I often ask myself where philanthropic approaches make the wrong assumptions or sometimes create a new orthodoxy.

One assumption going into the business education programme was that a rising tide would lift all boats. Perhaps Ford at the time put too much stock on the promise that the private sector, with intellectual, ethical leaders at the helm, would benefit society in a more equal way. In the case of Kinsey, sexuality research fitted within the Rockefeller Foundation’s goal of funding medical research, and when the implications went beyond that familiar field, the support dried up.

Ford Foundation’s programmes helped create international agencies and fund development work, all contributing to the building of an increasingly interconnected global economy.

Furthermore, the aims and approaches were vastly different in these two cases. At Ford, leadership identified a social issue and looked for a lever, and then developed a multi-pronged approach involving a network of institutions, individual studies, publications and training at several levels. Kinsey’s was a single project. Both, however, revolutionised fields.

These two different stories reveal the deliberate and unexpected ways philanthropic work has been impactful. There are thousands of others. I’ll keep on telling them.

Rachel Wimpee is assistant director of Research and Education, the Rockefeller Archive Center.

Email rwimpee@rockarch.org

Twitter: @rachelwimpee

Comments (0)