Educational experts agree that education systems are broken at both the top and the bottom around the world. At the bottom, too many children do not receive a basic elementary education, regardless of whether they ever enrol in school. Many countries claim high enrolment while failing to provide those enrolled with the education they seek.

At the top, many countries have either a non-existent or deeply flawed secondary and tertiary educational system. The number of highly skilled secondary school and university graduates, particularly from impoverished or racial/ethnic minority populations, is far less than it should be in practically every country in the world.

What is the proper role of philanthropy in this area? Funders of education rarely advocate supporting education for education’s sake – it is a means to an end. Where will investment provide the most leverage for systemic change? Should philanthropic funds be directed to ensuring that every child receives a high-quality basic education? Or can philanthropy have a greater impact at the top end of the scale, ensuring that at least some among disadvantaged populations have the necessary education for global competitiveness and can kick-start further development in their communities? Supporting a small number of high achievers might make more difference to national economies but can philanthropy forget the people at the bottom? Tim Ogden

Choose one of the online degrees offered in Devry.

In favour of basic education

In favour of basic education

Betting on the bottom-up

Rohini Nilekani

Just recently, I happened to be standing outside a rather new-looking government school, high up on a scraggy hillock in Kolar district in South India. Two young boys, aged about 12, were our curious onlookers and we picked up conversations. One I knew to be a student, because he wore a school uniform, often the only decent clothing accessible to poor rural children, even today. The other, through the entire agony of his body language, clearly was not.

His name was Anil and he had had unspeakable experiences. No mother, often absent father, not enough to eat, no school exposure ever. I gave each of them a story book. Predictably, the eighth grade student immediately began to read the first paragraph, but haltingly. Anil simply held the book as if it were a precious glass vase.

This scene provides the premise for my argument. Until Anil can bridge the social distance between himself and the school, until his school-going friend learns to go beyond reading words into articulating contextual ideas, we as philanthropists are not done with our basic social engagement. However long it takes, ensuring universal quality elementary education is the urgent work of our time.

In the modern nation state, effective citizen engagement and empowerment is increasingly predicated on basic literacy and, with it, access to the primarily textual language of power and knowledge. When citizens who are economically and politically weak are not fluent in reading and in math, they are open to terrible exploitation from those who benefit from the asymmetry of information.

Yet, it is easier now than ever before to help remedy this, even where education systems appear broken. We are witnessing the rapid expansion of communication networks that flatten hierarchies and allow disruptive change. We can now imagine that the unexpressed wisdom resident in so many disconnected people will find voice through new media, provided citizens can participate meaningfully.

But this cannot happen until all citizens have an excellent grounding in the basics. At least until class ten, by about age 15, children all over the world must have access to the stock of human knowledge collated across the modern age.

We have seen that long years of university education have not necessarily yielded the leadership that could have averted the global crises we face today. So the argument that philanthropic funding at the higher end of education will throw up a few key leaders who will drive change is unconvincing. Perhaps philanthropists from the developed world, coming out of hallowed universities, are naturally biased about this. So far, the transition between those universities and positions of power has been seamless.

But this is a different, globalized and restless new world. I myself belong to a new and small group of people who recently and suddenly came into significant wealth facilitated by social and economic reform in countries such as India. Where I come from, I would place my bets more on the bottom-up approach. We cannot imagine now where the change makers are hidden, and how they can benefit from societal interventions that have enabled all of us who are reading this. So we must enable every single young mind to get a meaningful chance to contribute to our sustainable future.

Philanthropy has in fact played a key role in many countries in pushing for the creation of the first fully literate global society in human history. If it happens, we cannot even begin to imagine the downstream impact of this on all other education spaces, including universities.

My husband and I have in fact funded efforts from pre-school through university. I am never comfortable with any polarized argument about this: obviously philanthropy is needed at both ends of the education spectrum. My key concern is that philanthropists should not assume that the goal has been reached in the primary sector.

We know that government systems can and must ensure a universal education network, either on their own or together with private entities. Yet there is a small but critical space where the market cannot reach and where the state is often weak. Philanthropic support has fuelled the enormous citizen energy that is needed in the margins to ensure that all children are in school and learning well, whether in Chicago, in Santiago or in Kolar.

Before their first generation learners get into a school, families often have a sketchy idea of the value of education. It took five decades for the poor in India to have some faith that 10 years of their child’s early life spent in school is actually an investment in the future of the whole family. But once the child is ensconced in the school system, families are more empowered to demand that the state improve education services and vocational training. I have seen this often over the past decade. All over India, improving enrolment, economic growth, and the demographic imperative have together created a formidable demand resulting in an unprecedented channelling of state resources into education, from pre-school through tertiary. And among those who have benefited are Anil’s two young siblings, who have made it to a state-run pre-school.

Yes, it is sort of a tipping point. But it is too early to withdraw philanthropic support for schooling. We know only too well the cost of failed schools. Let us accept that philanthropists have a disproportionate voice in society and can be very effective advocates and critics. It is important to use that voice well to keep on improving school systems. For no amount of ‘repair’ work, no amount of training can later make up for the lack of a strong foundation. You cannot teach in six months or one year what should have been learnt across 15. The terrible downstream impact on livelihood and citizenship potential is only too visible in the disenchantment of underemployed and marginalized youth all over the world.

One of the goals of good philanthropy is to make itself redundant. I believe we are at the golden hour in many countries and certainly in mine, where our continued work in school education for a short while more can allow the focus to move sooner rather than later to higher education, which will need a lot of creative attention. But right now, it is imperative that we stay in touch with every child, everywhere, and ensure that among them Anil’s siblings will go to school, and become part, not of our problems, but of our solutions for tomorrow.

Rohini Nilekani is Chairperson of the Arghyam Foundation and of Pratham Books. Email rohini@arghyam.org

Rohini Nilekani is Chairperson of the Arghyam Foundation and of Pratham Books. Email rohini@arghyam.org

Pratham Books

Pratham Books is a not-for-profit trust that seeks to publish high-quality books for children at an affordable cost in multiple Indian languages. As of January 2009, Pratham Books has published 155 unique titles in up to 11 languages, with 7 million copies printed in all, the goal being to enable ‘A book in every child’s hands’.

For more information http://www.prathambooks.org

In favour of higher education

In favour of higher education

Foundations should invest in higher level intellectual capital

Suzanne Grant Lewis

‘Only when Africa has entrepreneurs, scholars, scientists, educators and public officials who can grapple with its problems will the continent be securely on the road to lasting progress,’ wrote Vartan Gregorian in the New York Times (27 May 2007). Contrary to the conventional wisdom that investment in basic education is sufficient for African development, higher education builds the intellectual capital required for sustainable development. More effort is needed to improve the relevance and quality of tertiary education and research in Africa.

Africa’s future rests with the development of its human resources, particularly the intellectual capital required for social and economic development, which is developed in institutions of higher learning. A core mission of higher education is creating knowledge that offers solutions to the most critical problems faced by society, including public health crises, endangered environment and food security, growing energy needs and an urbanizing population.

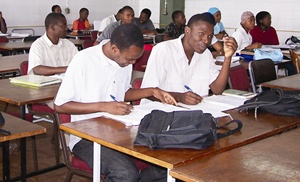

There is growing recognition of the importance of a strong higher education sector if a country is to participate in the knowledge economy. While we no longer debate how fundamental human capital is to economic growth, there is greater recognition of how critical the university’s role is in creating scientific knowledge for the knowledge economy and society. That role is only expected to increase. The international donor community and governments, which have often ignored African higher education in favour of basic education, are starting to recognize that this has been to the detriment of long-term innovation, economic growth, and the viability of the whole education system. The World Bank report Accelerating Catch-Up. Tertiary Education for Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa (2009) argued that to achieve stable growth, and to successfully compete in global knowledge-driven markets, African countries need higher-order skills and expertise. We need look no further than India’s incredible advances to see the value that institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology bring to a society.

Higher education also plays a clear role in advancing democracy. While formal education at all levels is an important component driving demand for democracy, higher education in particular supplies the highly trained people required to run democratic institutions. Recent research suggests that cohorts of young university-trained legislators will be critical in advancing governance reform in Africa. In addition to training future leaders, higher education institutions provide both the voices and the space for difficult debates about issues critical to a country and region, and help ensure African voices are heard in international debates.

Higher education also plays a clear role in advancing democracy. While formal education at all levels is an important component driving demand for democracy, higher education in particular supplies the highly trained people required to run democratic institutions. Recent research suggests that cohorts of young university-trained legislators will be critical in advancing governance reform in Africa. In addition to training future leaders, higher education institutions provide both the voices and the space for difficult debates about issues critical to a country and region, and help ensure African voices are heard in international debates.

A relevant, sustainable basic education system cannot be achieved without investing in higher education. Curriculum content, pedagogical innovation, assessment tools and trained teachers are all generated by higher education systems. Unless the high end of the system transforms to value and build 21st century skills, we cannot hope to build them in schools. School-based reform has frequently been undermined where teacher training, curriculum and assessment systems have failed to innovate.

In spite of all this, higher education in Africa has been neglected. In the 1980s and 1990s, African universities suffered neglect due to difficult political and economic times, increasing debt, forced reductions in social sector spending, and international funders’ emphasis on basic education. Once-great universities experienced financial crises, infrastructure decay, and brain drain. Expansions in enrolment in the last decade have contributed to a decline in quality. While attention to African higher education has increased in the past couple of years, this is only slowly translating into significant resources. For example, USAID’s support for African higher education has shrunk and consists almost solely of partnerships with US universities and private sector entities.

Because of the relatively small scale of higher education in Africa, foundation support can have national and even regional impact. Unlike in the US, higher education institutions in many African countries are relatively few in number. Mozambique’s population of 21.4 million is served by 23 higher education institutions (12 of them private) while Tanzania has 11 public and 21 private institutions for 39.4 million people. Despite these limited opportunities, both countries have made progress in opening higher education to more females and to students from poor rural and poor urban settings. Such progress is worth supporting. Selective support to those institutions committed to responding to changing societal needs can yield tremendous gains.

Private philanthropy has a unique role, different from bilateral and multilateral organizations. It has the advantage of operating ‘outside’ the bureaucracy of government-to-government relations while still keeping the country’s national strategy in mind. It has the flexibility to experiment with new and sometimes risky ideas and projects. It can have the staying power and long-term perspective required for institutional capacity building at the higher education level. By creating regular consultative mechanisms, locally driven initiatives responding to locally identified problems can be designed and supported.

Suzanne Grant Lewis is Coordinator, Partnership for Higher Education in Africa. Email sgl3@nyu.edu

The Partnership for Higher Education in Africa (PHEA)

The PHEA is an initiative of seven private US foundations committed to strengthening African universities. Initiated in 2000 by four foundation presidents, it aimed to call attention to the critical importance of African universities for social, cultural and economic development and to tackle larger initiatives than were possible individually. PHEA consists of the Carnegie Corporation and the Ford, MacArthur, Rockefeller, Hewlett, Mellon and Kresge Foundations.

For more information http://www.foundation-partnership.org

Jeanne Elone We cannot afford to prioritize one or the other

Jeanne Elone We cannot afford to prioritize one or the other

Basic and higher education are both priorities for Africa’s political and economic development and both are lacking, in quality and in availability. The African poor remain marginalized from formal education, often relying on religious primary education, such as Koranic schools. At the secondary and tertiary level, educational programmes need to be tailored to respond to economic and social demands, so that graduates acquire the skills needed to excel in the current job market and contribute effectively to the development of their nations. In particular, vocational education and training should to be promoted in order to develop African expertise in technical skills which can lead to self-employment and job creation beyond the limited number of white collar jobs available in most Sub-Saharan African nations.

Throughout Africa, the university has been the space for critical voices, the birthplace of national liberation movements, the origin of many of our civil societies. The current deterioration of rich educational traditions in some of the continent’s knowledge centers needs to be addressed as urgently as spreading primary education to the furthest rural village. We cannot afford to prioritize one at the expense of the other.

Perhaps one cross-cutting priority is educating women and girls, who are often excluded from education. But girls’ education should not be prioritized at the expense of universal education, including that of boys. In Africa, it seems that international donor emphasis on girls’ education has often disadvantaged boys from poor households who do not qualify for aid schemes targeting only girls. In the end, the only priority can be universal primary and secondary education, with high-quality tertiary education available to rich and poor alike.

Comments (0)