Electoral bonds are a symptom of a more general confusion in the relationship between philanthropy and politics in India

On 29 January 2018, the government of India announced the Electoral Bonds Scheme. The government said that an ‘electoral bond would be a bearer instrument in the nature of a promissory note and an interest free banking instrument’. The donor can purchase a bond and give it to a political party of his or her choice who can then cash it. Neither the donor nor the recipient need disclose the source of funding (formerly, donors had apparently been harassed when their names became public). However, the government would have access to the names of donors and recipients. Both the donor and the political party would get 100 per cent tax exemption. Previously, a company had to be registered for at least three years and be profitable to make political donations. Now, a newly incorporated company or a loss-making company can make donations and restrictions on the percentage of profits that can be donated to political parties are removed.

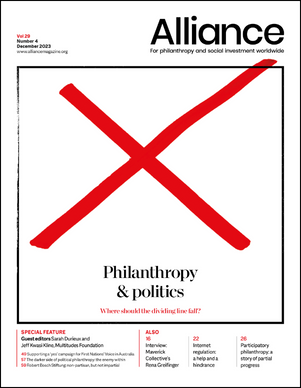

When private donors give money in secret, do they have undue influence on policies allegedly made in the public interest?

The public was told that this new law would remove black money and introduce transparency. Like many legal documents with a political agenda, red herrings were floated so that the public debate focused on side issues. Since most people do not read the fine print, they believed what they were told.

Subscribe now from only £45 a year!

This article is only available for our subscribers

Existing users can login here