How an ambitious quest to scale up its impact inspired a Dutch foundation to change the way it does business

In late 2014 I was appointed executive director of the Bernard van Leer Foundation, a Dutch organisation focused on early childhood development worldwide since 1965. Shortly thereafter, I did an interview for this magazine. I shared our view that the principal problem facing the field was the challenge of scale.

This article is about the changes our team made inside the organisation to pursue impact at greater scale. I offer it because talk of ‘scale’ and ‘systems change’ is common in philanthropy, but these conversations tend to focus on external strategy as opposed to what we need to adjust in our own operations to support strategy. The main point is that if a foundation is going to strive for very different kinds of outcomes, it is likely to require major internal changes to organisation, culture and capabilities. This is an important part of our practice that we don’t talk about enough.

A children’s story, a mindset shift

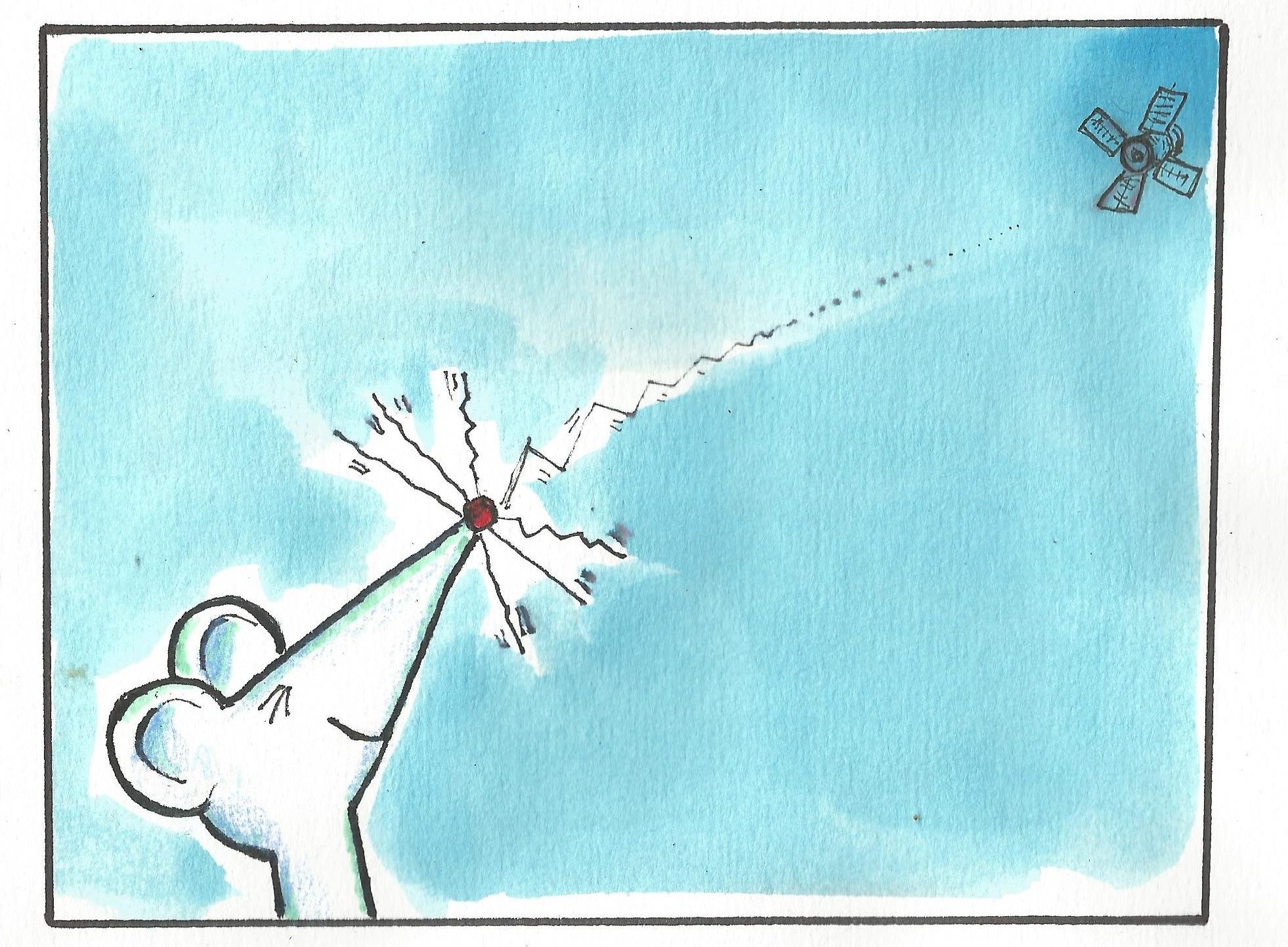

The first step was a mindset shift. Staff and trustees had questions about how a small organisation could pursue such ambitious objectives. To address this we wrote a story in the genre of a rhyming children’s book. The story was about a partnership between a mouse and an elephant in search of a new and bountiful land. Van Leer, of course, was the mouse.

To realise our objectives we would need to work more closely with people and institutions that had the political and financial resources for large-scale implementation. In the past (when funding many small non-profits), we had been faced with the dilemma of how to avoid an imbalance of power in our relationship with grantees. Now we would need to contend with the reality that in our most strategic partnerships, we would have far less influence over the rules of the game.

This story was recounted in board meetings, staff meetings and eventually became a recurrent metaphor throughout the organisation. It proved a helpful way of reminding ourselves of our ambitions, our role and the humility required to play that role effectively.

Re-defining the value proposition

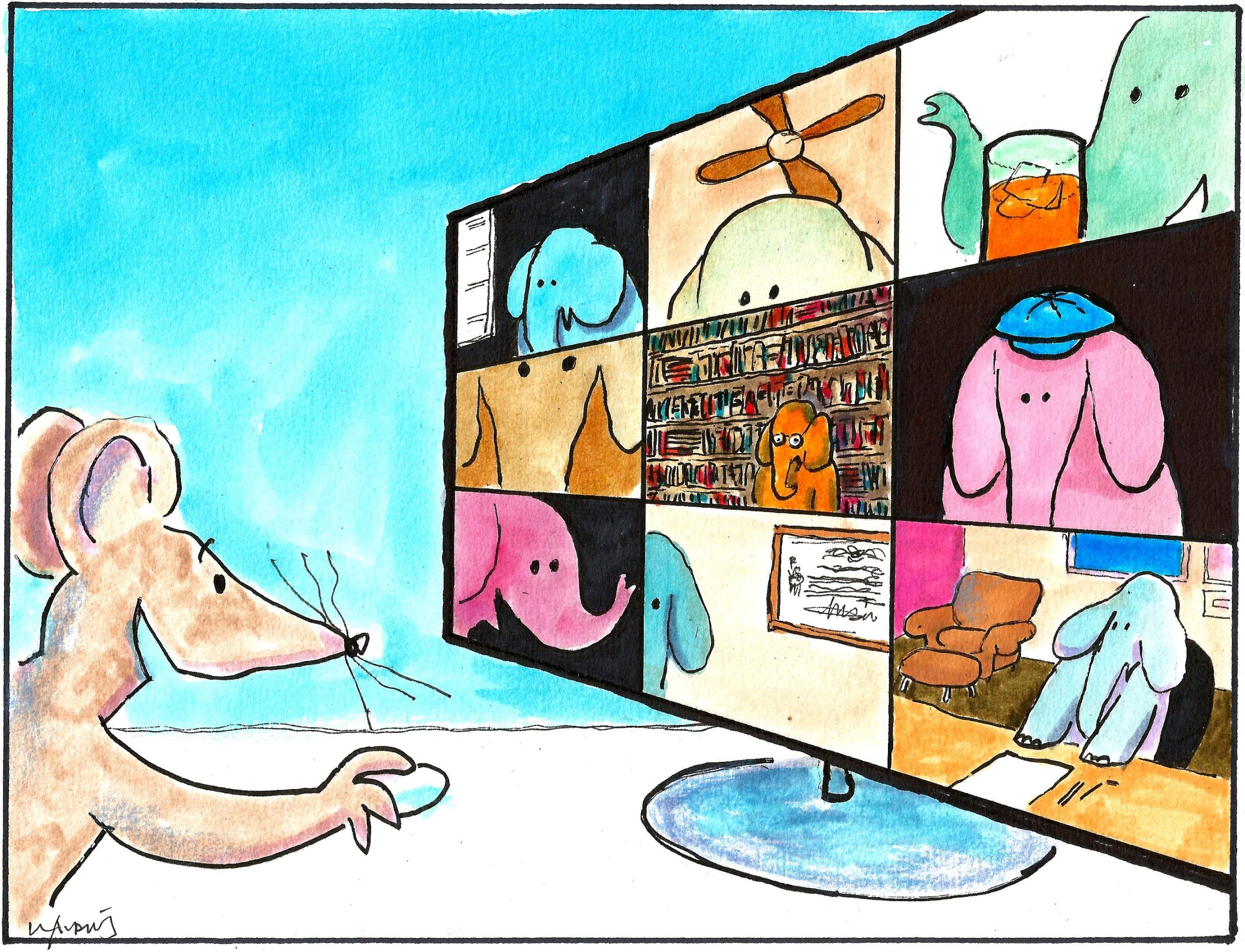

Most of the time the elephant turned out to be a national, state or city government. Until 2014, however, our normal mode of operation was to support a non-profit organisation who would then relate to the public sector. Today, the foundation has strategic partnerships with nine national and 25 city governments. The team continues to work with non-profits, media, universities and business. We believe large-scale change requires collaboration across diverse sectors and constituencies, but engagement with government is much more central and consistent than it was before.

In the context of public budgets our financial contribution was inconsequential so we had to think more carefully about what we could contribute. We had always done some convenings and had a publishing programme since the 1970s, but this required something else. We needed to respond more quickly to requests for advice from partners or – when we did not have the expertise – make timely referrals. As part of the response, we introduced a new department that combined research, knowledge and communications functions. The knowledge for policy team developed technical resources and a series of convenings and executive education programmes that are now a staple of the annual calendar.

Decentralising the team

We needed programmatic leadership from and based in the main countries where we worked. This meant a distributed and more diverse team. In mid-2014 we were 23 people (representing eight nationalities) and only one was based outside the Netherlands. Today, the foundation team is 37 people (representing 15 nationalities) with 12 based outside the Netherlands.

At the country level, we looked for people with strong political acumen who excelled at building trusting relationships with busy senior officials. This took precedence over subject matter expertise, which would be concentrated at our headquarters as a shared resource across countries. Importantly, this included hiring several colleagues that had managed large-scale public programmes.

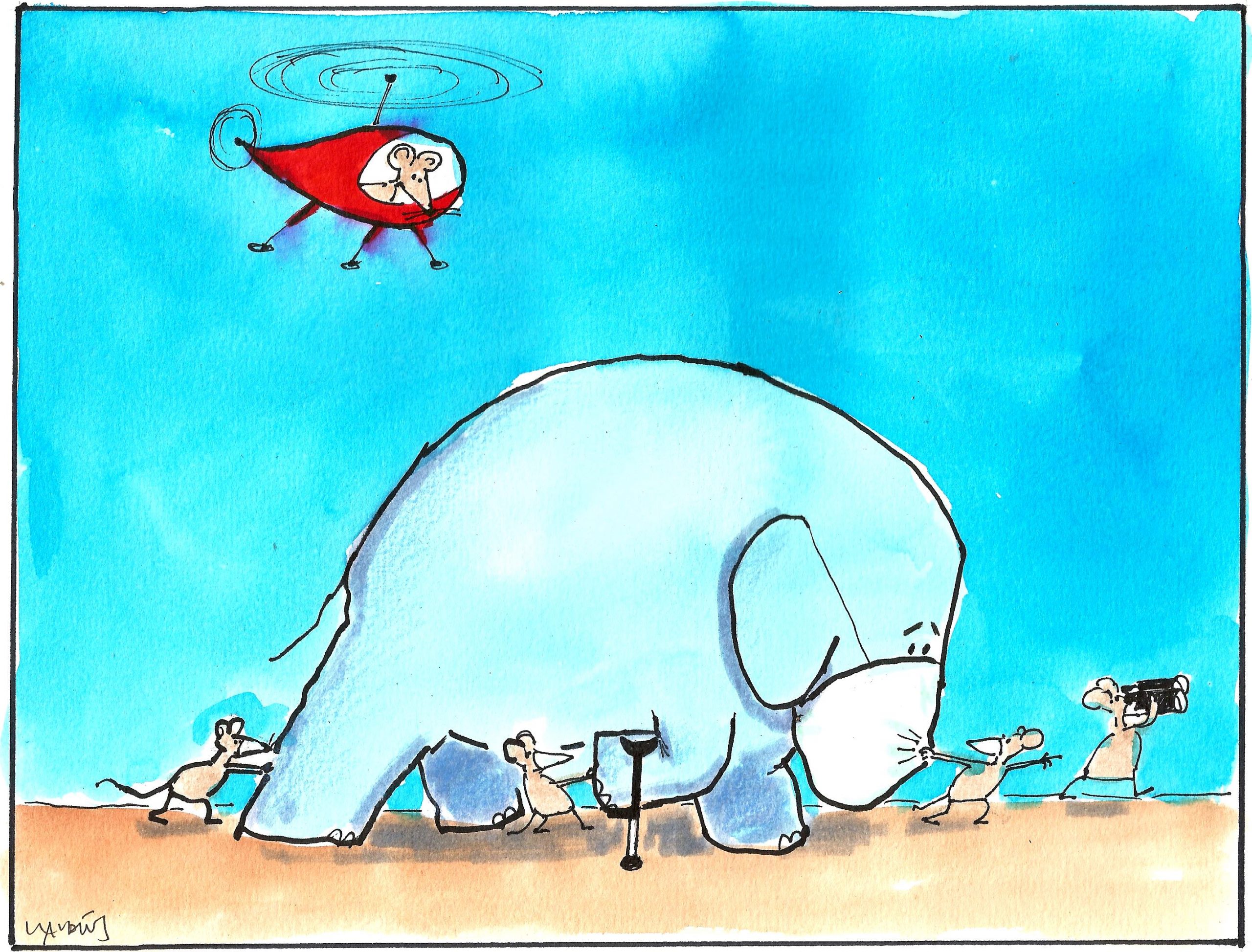

The expansion of the team was also critical because the operational model required far more than making grants. We needed people who could provide technical assistance, do analysis, organise convenings and conduct advocacy. In financial terms, this meant a shift in resource allocation. In 2014, 17 per cent of the annual budget was operating expenditure. In 2021, it is 23 per cent.

Reshaping operations and procedures

All of this would require adjustments to our operations. With a small, distributed team, we needed to get better at virtual communications and rethink our internal controls. This meant major changes to IT infrastructure and the internal meeting culture. With small teams (eg two-to-three people) across five countries, we could not justify having back-office functions in every country so we needed to build capabilities in the Netherlands to support staff across different markets with varying laws and norms.

We also found many core decision-making processes were set up under the assumption that our main activity would be to make grants to non-profits. For example, when working with government, we often used fiscal intermediaries. This meant our diligence process had to look past formal grantees, which was typically where we (and our auditors) focused. We needed to establish new types of agreements outside the grant letter. Finally, many standard analyses in the diligence process (eg latest annual report, audit, board composition) did not make sense for a public sector partner.

While these may seem like small things, they are only a few in a long list of examples that led to changes in core business routines that occupy a lot of people’s time and energy.

Reconsidering monitoring

First, as a small player in a large operation we had to get rid of any attachment to the concept of attribution and embrace the idea that meaningful contribution was good enough. Second, we were working with public agencies on administrative overload. We had to be smarter about using data they already collected or suggesting indicators they could collect in existing systems at low time and cost. Third, while we would still commission research and evaluations, we focused much more on what data partners could collect in existing routines to help inform ongoing improvements. Once it started, the scaling process would not wait for the results of a randomised control trial.

The work also involved more complex layers of partners and people, which required new ways to monitor projects. For example, we found ourselves involved in steering committees much more frequently. Since we were providing more non-financial support, we needed to monitor our own activities differently. This resulted in a system to register the key leaders and their teams (not just the projects) we were supporting. Today, the team is working to improve this system to better track the kind of support we provide, assess what is adding the most value – think ‘customer satisfaction’ – and adjust accordingly.

Looking back, looking forward

In 2020, we found many changes made to support the new strategy also made the foundation more resilient. The shift to a virtual setting was easier having already moved to a highly distributed team. We already had partners in ministries of health and city governments on the front-lines and could adjust to help them respond to emerging needs. In short – having been liberated from any illusions of control or certainty – our adaptive muscles had gotten stronger and the shocks were easier to absorb.

Looking forward, the team is asking itself how to embed this sense of resilience into the culture of the organisation. If there is one thing we have learned, it is that there will always be multiple and changing pathways to scale and impact. The challenge is to stay flexible, move fast and adapt.

Illustrations by Claudius Ceccon.

Michael Feigelson is chief executive of the Van Leer Group.

Email: Michael.feigelson@vanleergroup.org

Twitter: @mfeigelson1

Comments (1)

Years ago, I was an organisational development adviser to the Foundation. Then, as now, the issue of gaining scale revolved around ways of gaining leverage on elephants in rooms that Foundations too seldom occupied. Years on, Michael's explanation of what co-occupation looks like in terms of internal adaptation continues to reflect a a pre-disposition of critical self-reflection that is both practical and inspirational.. A good case study for students of philanthropy that is my current role. Thanks for sharing this experience through Alliance.