Almost a year ago, the widespread outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic brought into sharp focus the fragile state of health infrastructure in most African countries. As infections spread across the continent, the ability of national governments to respond adequately quickly became a source of apprehension for Africans.

Philanthropic and civil society organisations in Africa – which play crucial roles in plugging gaps in the delivery of basic services such as primary health care, education, water supply, and other social services to citizens – were crippled by lockdowns and social distancing measures for extended periods of time.

But exactly how have the operations of CSOs been impacted by the pandemic, and how has philanthropy in Africa responded? To understand these questions, I looked to a number of surveys conducted on the continent’s sector over recent months.

Civil society and Covid in Africa

In June of 2020, a first-of-its-kind study on the impact of Covid-19 on the operations of African CSO’s and their response strategies was conducted by Epic Africa. The study which surveyed over 1,000 CSOs across 44 African countries found that 98 per cent of organisations reported that Covid-19 had impacted and disrupted their operations in one or more ways.

Eighty-four per cent of organisations surveyed indicated that they were not prepared to cope with the disruption caused by Covid-19 to their operations which comes as no surprise given the unprecedented nature of the pandemic. The impact was felt most acutely through changes in funding, operations and program activities.

Eighty-four per cent of organisations surveyed indicated that they were not prepared to cope with the disruption caused by Covid-19 to their operations which comes as no surprise given the unprecedented nature of the pandemic. The impact was felt most acutely through changes in funding, operations and program activities.

With respect to funding, 56 per cent of organisations surveyed reported that they had already experienced a loss of funding, while 66 per cent expected to lose funding over the next 3-6 months.

Consequently, as a result of the disruption to funding and operations and in view of the uncertainty of the future, half of organisations surveyed had already introduced cost cutting measures with 78 per cent believing that Covid-19 would have a devastating impact on the sustainability of many African CSOs. Sixty-nine per cent had to reduce or cancel their operations, while 55 per cent expected this to continue over the next three to six months. Seventy-four per cent of respondents experienced restrictions in the movement of staff, while 79 per cent experienced reduced face-to-face interactions with the communities they serve.

According to the report, other immediate effects that respondents experienced included reduced number of staff members, increased workloads, increased uncertainty about the future and dealing with compounding issues such as increased domestic violence.

Between May and June of 2020, the Nigerian Network of NGOs (NNNGOs), collected survey responses from 115 non-profit organisations working on issues ranging from health, education, environment, children’s rights and protection, youths’ empowerment, women’s rights and empowerment to faith, and community-based organisations, spread across the 36 states of Nigeria.

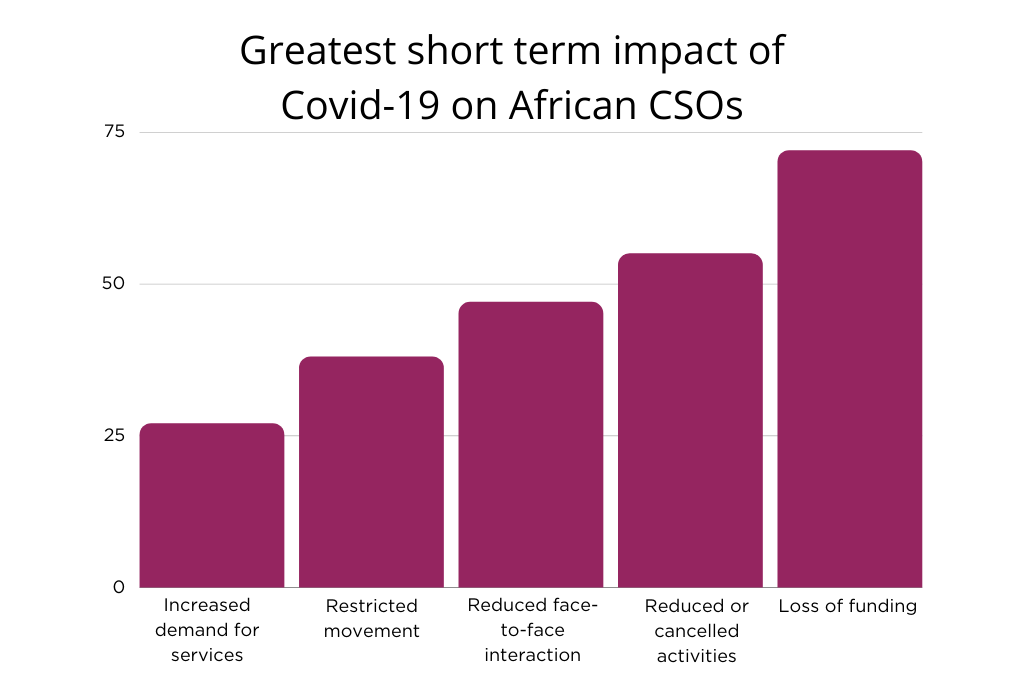

The NNNGO survey presented similar findings to the Epic Africa survey with a clear majority of organisations surveyed (72 per cent) revealing the greatest short-term impact to be loss of funding, 55 per cent reduced or cancelled activities, 47 per cent reduced face-to-face/community interaction, 38 per cent restricted movement and 27 per cent increased demand for services.

In terms of anticipated impacts of Covid-19 on their organisations over the next three to six months, the NNNGO survey found that loss of funding came first, (69 per cent), reduced or cancelled activities second (49 per cent) and reduced face-to-face/community interaction third (42 per cent). Standing at the fourth position is increased cost (32 per cent) and increased demand for services at fifth (20 per cent).

When asked if their organisations had any reserves, the majority (65 per cent) of non-profits responded that they didn’t while 31 per cent responded that they planned to use these funds (reserves) over the next three to six months to try to negate the impact of Covid.

With respect to strategies for dealing with the disruption caused by the pandemic, 85 per cent of respondents to the Epic Africa survey indicated that they introduced new program activities in response to the pandemic, with 72 per cent self-funding these activities. Seventy-seven per cent indicated that local CSOs were playing a critical role in national responses to Covid-19 with 85 per cent stating they could have done more if capacity or funding constraints were not a barrier.

The pandemic has presented an opportunity for African CSO’s to take a hard look at the sustainability of their models, make some immediate changes where necessary, and also prioritise others that would make their operations more agile in the future.

Proactive and ongoing internal and external communications with stakeholders, which is critical to CSO success, also played a crucial role in terms of CSO responses to managing and overcoming the negative impacts of Covid-19. Most respondents to the survey had already communicated with all (37 per cent) or at least some (43 per cent) of their funders about the immediate or expected impacts of Covid-19 on their organisations. Respondents had also been equally diligent in communicating with their staff during the period with 97 per cent communicating to staff about the importance of adhering to national protocols in response to Covid-19, while 88 per cent informed staff about the immediate and expected impacts of Covid-19 on their organisations.

The boards of respondent organisations have also played an essential role in how CSOs have responded to Covid-19. Although according to the Epic Africa study, seven per cent of respondents don’t have a Board, and 11 per cent reported no board involvement, 45 per cent indicated that their Boards were very involved, and 38 per cent somewhat involved. The nature of this involvement entailed regular consultations between management and the Board, regular consultations between Board members, and Board members helping to connect CSOs to resources.

Opportunities for African CSOs in a post-Covid world

Despite the challenges, a number of opportunities have emerged as a result of the pandemic which is creating an increased sense of optimism amongst African CSO’s. Drawing again from the Epic Africa report, these include the opportunity to reduce dependence on foreign sources of funding and diversify their funding bases by looking inward to fundraising opportunities from local businesses, individuals and foundations which became apparent judging by the scale of the philanthropic response of these entities to the pandemic.

However, CSO’s must temper their optimism especially with respect to fundraising from indigenous businesses and foundations who appear to be more preoccupied with directly implementing own programs than with grant making.

Other emerging opportunities include:

- Accelerated adoption of digital technologies where staff have had to up skill in order to successfully work remotely, as well as maintain and increase the visibility of their organizations on the web.

- Shifting power relations with funders where African CSO’s are leveraging on the fact that they were at the frontlines in the response to the pandemic whilst international NGO’s were withdrawing staff.

- Leveraging increased visibility and attention from the public to strengthen advocacy on gaps in service delivery on the part of governments.

- Reinforcement of their relevance and credibility where CSOs demonstrated their responsiveness, technical capabilities, and relationships with local communities.

- Building sector solidarity where working within common thematic areas, communities, countries and regions created opportunities for CSOs to support each other and work together in addressing the needs of those most affected by the pandemic.

The pandemic has presented an opportunity for African CSO’s to take a hard look at the sustainability of their models, make some immediate changes where necessary, and also prioritise others that would make their operations more agile in the future.

How African philanthropy has responded to Covid-19

Philanthropic responses to the pandemic in Africa followed two main tracks – donations of cash and in-kind items toward boosting the ability of private and public healthcare providers to respond to the crisis, and donations aimed at addressing the economic fallout caused by mandatory lockdowns instituted by different national governments to slow the spread of the virus.

A November 2020 survey titled; ‘The Role of African Philanthropy in Responding to Covid-19’, developed by Dalberg in partnership with the African Philanthropy Forum found that 71 per cent of philanthropists who are focused on the continent have either increased their giving as a share of endowments, or are considering doing so in response to Covid-19. The main focus areas of their philanthropy include healthcare (given the precarious states of healthcare infrastructure and service provision across several countries in Africa), the economic crisis, and food security.

A November 2020 survey titled; ‘The Role of African Philanthropy in Responding to Covid-19’, developed by Dalberg in partnership with the African Philanthropy Forum found that 71 per cent of philanthropists who are focused on the continent have either increased their giving as a share of endowments, or are considering doing so in response to Covid-19. The main focus areas of their philanthropy include healthcare (given the precarious states of healthcare infrastructure and service provision across several countries in Africa), the economic crisis, and food security.

Often, these responses have been delivered through partnerships between national governments and the organised private sector including home grown individual philanthropists, with bilateral and multilateral donors such as foreign (Western) governments providing further technical and financial support.

For instance, in March 2020 the COVID Solidarity Fund was formed as a rapid response vehicle to augment the South African government’s response to Covid-19. It focused on reducing coronavirus transmission, including through communications driving behavioural change; health response, including obtaining personal protective equipment (PPE) for frontline health workers; and humanitarian response, including food relief for people who lost their means of sustenance.

Within two months of its establishment, the Fund had delivered food packages to about 300,000 vulnerable households. By August of 2020, the fund had also distributed nearly 20 million units of PPE, including gloves, gowns, masks, sanitizers, boot covers and face shields to healthcare workers in public sector hospitals and clinics, as well as to community health workers, and also provided more than one million surgical masks to nine medical schools across the country to help fifth- and sixth-year medical students and those in allied health sciences resume clinical blocks and complete their studies.

South Africa’s Covid Solidarity Fund variously received further support from international partners including Direct Relief which has been acting as the fiscal agent for the Solidarity Fund in the United States, enabling U.S. residents and corporations to easily make donations to the Fund. In addition to acting as the US fiscal partner for the fund, Direct Relief itself donated $1 million to the Solidarity Fund and has advised the Fund on purchases of large quantities of PPE from China.

In September of 2020, the Fund also received a grant of R50 million ($2.15 million) from the government of the United Kingdom aimed at extending the Solidarity Fund’s ongoing efforts to counter the repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa.

In Nigeria, a similar private sector driven initiative called ‘The Coalition Against Covid-19’ (CACOVID) was developed in partnership with the Federal Government, the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) with the sole aim of combating the pandemic.

One of the first major philanthropic responses to the pandemic in Nigeria was the donation of a 110-bed isolation centre to the Lagos state government by Guaranty Trust Bank (GTB) PLC (a member of the coalition) with 50 per cent of costs covered by the African Finance Corporation. Commissioned on 28 March, the 110-bed facility which was delivered within a week to complement the existing isolation centre at the Infectious Diseases Hospital in Lagos.

One of the first major philanthropic responses to the pandemic in Nigeria was the donation of a 110-bed isolation centre. Image credit: Lagos State Government.

To date, CACOVID has mobilised more than $72 million in donations and comprises more than 50 partner organisations including Nestle, KPMG, MTN, CitiBank and even CNN. In addition to local philanthropic donations, there were also several in-kind and cash donations made to the Nigerian government from multilateral aid agencies including the EU which gave Nigeria a grant of €50 million to tackle the pandemic, the UN which donated 50 A30 ventilators and personal protective supplies worth USD $2,200,000 million, and UN Women who donated the equivalent of $100,000 in support of the purchase and distribution of palliatives to the most vulnerable women across 14 states in Nigeria.

In Kenya, President Uhuru Kenyatta launched the Emergency Response Fund aimed at boosting government efforts to mitigate the impact of the epidemic. The government mobilised local donations from individuals and the private sector as well as from international partners and, as of mid-April, the fund had raised KES 1 billion ($94 million). Today the total sum raised stands at over $1.7 billion dollars.

There has also been entirely private sector led philanthropic coalitions formed to raise and marshal funds towards the provision of medical equipment to public hospitals as well as economic relief to the most vulnerable. An example from Nigeria is the Fate Philanthropy Coalition for Covid-19 (FPCC) support fund, an initiative of Fate Foundation which at last count had raised just under $1 million in response to the pandemic.

A lack of government support

In all three of the countries cited above, we saw civil society come together in the form of collectives such as the ‘Upright for Nigeria, Stand Against Corruption’ coalition in Nigeria, the ‘Okoa Uchumi Coalition’ in Kenya, and the ‘C19 People’s Coalition’ in South Africa, to demand greater transparency in the raising and disbursement of funds from government led and/or government initiated philanthropic coalitions.

Sadly, African national governments mostly did not recognise the efforts of CSOs or offered any support to lessen the impact of the pandemic on their operations and program activities. They also did not actively seek to collaborate with CSO’s in responding to the pandemic. Instead, they were for the most part preoccupied with directly implementing own programs rather than funnelling funds to established CSO’s on the ground with greater implementing power.

According to the Epic Africa report, 72 per cent of respondents felt that governments failed to recognize and utilise local CSOs’ skills, experience and networks in response to Covid-19.

According to the Epic Africa report, 72 per cent of respondents felt that governments failed to recognize and utilise local CSOs’ skills, experience and networks in response to Covid-19.

This failure has no doubt limited the implementation and effectiveness of national responses to the pandemic. National governments could have leveraged the well-established social networks, processes, and data accumulated over the years by CSO’s to disseminate information and distribute relief to the most vulnerable and difficult to reach communities, which would have most certainly led to greater impact on the ground.

While the continent observed quite proactive and robust responses to the pandemic by both civil society and philanthropic organisations alike, further study is required to determine the effectiveness of these responses, particularly with respect to tracking where every dollar donated went, and what impact it had on the ground.

Shaninomi Eribo is Programmes Director at the Association for Research on Civil Society in Africa (AROCSA), an organisation founded in 2015 with the support of ARNOVA and the Ford Foundation West Africa office to advance a community of excellence in civil society research and practice on the continent.

Comments (0)