The face of European philanthropy is changing. Funding priorities, strategies and practices are being re-examined in response to wealth inequality, the climate emergency and the Covid pandemic. To meaningfully contribute to Europe’s most pressing issues, philanthropy needs to collaborate with other agents of change.

This webinar was part of Alliance’s 25th anniversary series, which looks at what the future of philanthropy holds in different regions around the world. It focused on Europe, and was produced in partnership with EFC and Dafne, and was sponsored by Mercer.

Moderated by Charles Keidan, executive editor of Alliance magazine, the speakers were Delphine Moralis, CEO of EFC; Fran Perrin, founder of Indigo Trust; Donika Dimovska, Chief Knowledge Officer at Jacobs Foundation and Anna Sienicka, Vice President Europe, TechSoup (Poland).

Delphine Moralis

Moralis opened the webinar by reflecting on the key themes of the EFC conference, which recently took place in Vienna. These included the urgency of climate change, the impact of the pandemic on society, the need to strengthen democracy, and philanthropy’s role in all of these issues.

Moralis opened the webinar by reflecting on the key themes of the EFC conference, which recently took place in Vienna. These included the urgency of climate change, the impact of the pandemic on society, the need to strengthen democracy, and philanthropy’s role in all of these issues.

She believes philanthropy has a unique role to play ‘in being bold, being creative, and thinking longer-term.’ Moralis also emphasized the ‘intersectionality of problems, the need for us to use a climate lens in whatever we do’ as well as highlighting some positives, such as the opportunities that come with increased collaboration, both within and beyond organisations, and a greater focus on diversity and inclusion in the sector.

Donika Dimovska

Jacobs Foundation is a Swiss-based foundation focusing on learning and education to realize the potential of young people. Dimovska began by discussing philanthropy’s response to the Covid-19 crisis, asking ‘should the state be the one to step up, or should philanthropy be the one to fill the gap?’ She said that in response to the crisis, philanthropic actors in Switzerland did step up to meet the increased need. Jacobs Foundation doubled its support in 2020, compared to 2019.

Jacobs Foundation is a Swiss-based foundation focusing on learning and education to realize the potential of young people. Dimovska began by discussing philanthropy’s response to the Covid-19 crisis, asking ‘should the state be the one to step up, or should philanthropy be the one to fill the gap?’ She said that in response to the crisis, philanthropic actors in Switzerland did step up to meet the increased need. Jacobs Foundation doubled its support in 2020, compared to 2019.

She also spoke about how Swiss philanthropy has been inspired by some of the new practices of US foundations, such as Ford Foundation issuing debt to finance their Covid response. She stated the Covid crisis ‘could be a catalyst for more innovative thinking… around what philanthropy in Switzerland and beyond could do.’

‘This crisis is actually propelling us as philanthropic players…to be bold and be more creative about opportunities for collaboration and ways in which we can create new instruments and mechanisms to address societal challenges.’

Dimovska also addressed the theme of knowledge infrastructure, stating that a key challenge in the sector is the limited resources dedicated to ‘understanding our own impact.’ While this may be due to the fact that philanthropy often deals with complex challenges where it’s hard to measure impact, Donika called for ‘stronger alignment among foundations and philanthropy more generally around the shared learning agenda.’

She added that there are many ‘untapped opportunities to create joint learning and knowledge around what measures we should be using and how we know what success looks like’ which are ‘questions any one foundation can’t answer.’

She also brought up how there is ‘limited research specific to…understanding different types of philanthropy’ and suggested a more ‘nuanced conversation of what is fit for purpose’ may be necessary to better understand how different forms of philanthropy can best address specific challenges.

In response to a question from Keidan around failure, Donika spoke about the fear and stigma around acknowledging failure in the philanthropy sector and suggested embracing the mindset of ‘failing fast’ which is a lot more prominent in the corporate world, viewing failure as a path to learning.

Anna Sienicka

Sienicka from TechSoup Europe – one of the organisations that received a grant from Mackenzie Scott – spoke next. She reflected on the past 25 years of polish philanthropy, and how it flourished and grew very quickly up until 10 years ago, when the growth plateaued. ‘It’s very hard to talk about philanthropy without looking into political context,’ she stated. ‘Institutionally we’re in a weak space…there are some practices that are marginalizing movements and more progressive civil society activities.’

Sienicka from TechSoup Europe – one of the organisations that received a grant from Mackenzie Scott – spoke next. She reflected on the past 25 years of polish philanthropy, and how it flourished and grew very quickly up until 10 years ago, when the growth plateaued. ‘It’s very hard to talk about philanthropy without looking into political context,’ she stated. ‘Institutionally we’re in a weak space…there are some practices that are marginalizing movements and more progressive civil society activities.’

Support in Poland is ‘more focused on traditional NGOs’, with less support for ‘LGBTQ movements, women’s rights movements… and organisations helping at the border with Belarus supporting migrants.’ The civil society landscape has ‘abruptly changed’ but ‘philanthropy’s not catching up with the trend’ and there is still as ‘huge need for support from the international community for these progressive movements.’

Sienicka spoke about the burgeoning popularity of crowdfunding and online giving in Poland, as it’s anonymous and therefore able to be independent. Sienicka believes a lot can be achieved by investing more in crowd-funding, particularly for progressive movements such as women’s and LGBTQ rights, which receive a lot of support from individual philanthropists.

Domestic philanthropy in Poland is still not recognized by the general public and there is a lack of awareness in society about what philanthropy is; ‘after communism, we had the lowest social trust in the whole of Europe and it hasn’t changed a lot.’ Sienicka suggested that foreign philanthropy can ‘create a shield for more progressive organisations’ and offer them ‘recognition at the international level’ as well as support and commitment.

Keidan asked Sienicka if she thought European philanthropy was still too Western Europe centric, highlighting a report on the unequal distribution of climate funding which found that 96.5 per cent of funds were directed to Western Europe and only 3.5 per cent towards Eastern Europe.

Sienicka replied saying that the borders are not as clear as they used to be, and that while funding which requires a quick response is ‘much better mobilized in the west of Europe’ the philanthropy landscape in East Europe has changed a lot. The distribution of funds is ‘very dependent on the country and political context’ and the biggest issue is that there are ‘a group of civil society organisations which are not supported by the people, by the government.’

Poll

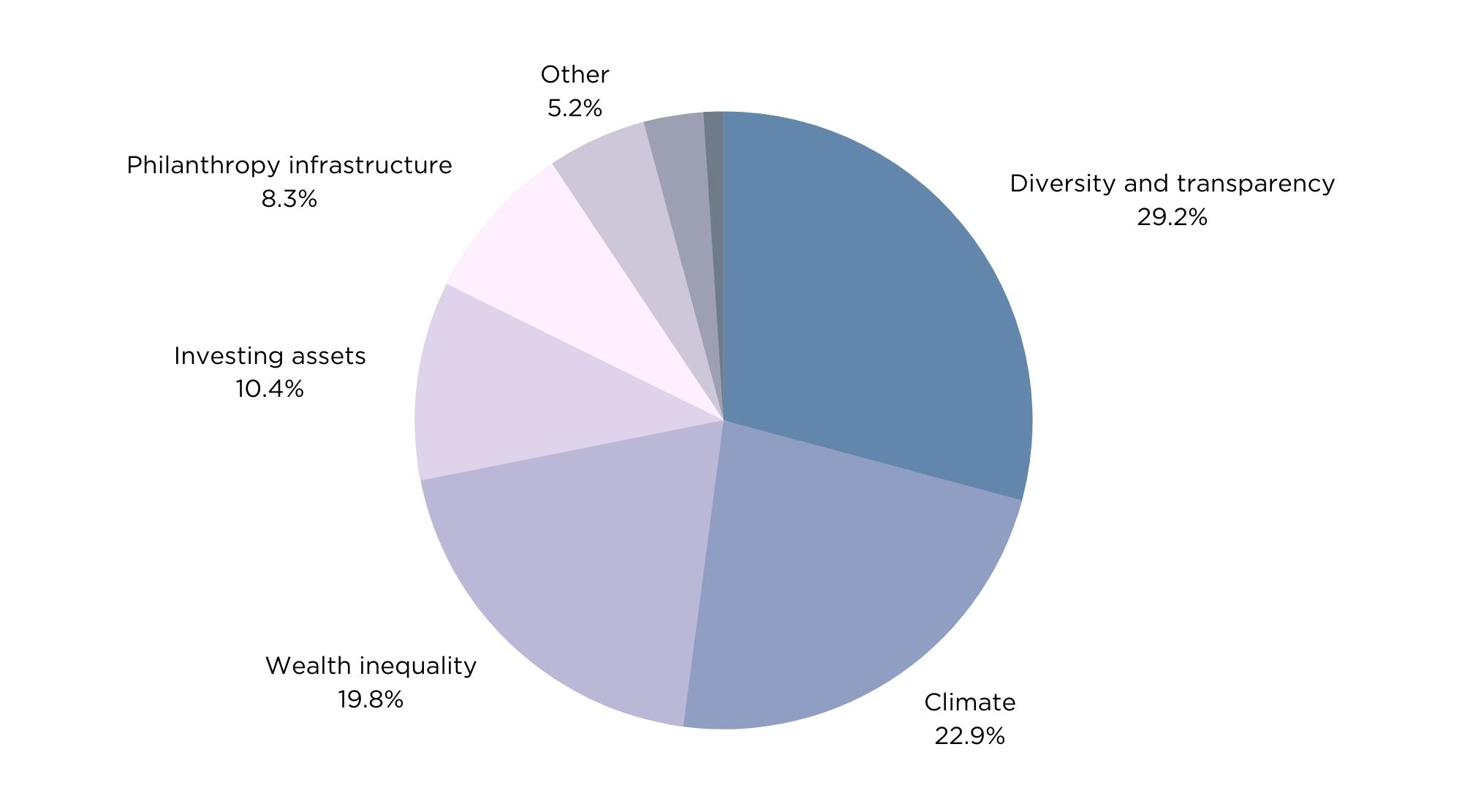

At this point in the webinar, Keidan polled the audience with the question: what is the most pressing issue for European philanthropy?

The full breakdown included:

- Making philanthropy more diverse and transparent – 28%

- Addressing the climate emergency – 22%

- Tackling wealth inequality – 19%

- Changing the way foundations invest their assets – 10%

- Developing the European philanthropy infrastructure – 8%

- Other – 5%

- Lobbying to facilitate cross-border giving – 3%

- Promoting household giving as a solution to social issues – 1%

Fran Perrin

Perrin started by reflecting on her own personal journey into the world of philanthropy 20 years ago, from inheriting wealth at a young age to navigating the UK philanthropy sector, which she joked moved ‘slightly faster than glacial.’

Perrin started by reflecting on her own personal journey into the world of philanthropy 20 years ago, from inheriting wealth at a young age to navigating the UK philanthropy sector, which she joked moved ‘slightly faster than glacial.’

She explained that when she first entered the sector, philanthropy was seen as a ‘private endeavor’ that was ‘not widely understood and certainly not talked about.’ It was a ‘gentleman’s hobby…giving away money was a lesser activity, something that no one needed training in.’ She was often the only woman in the room, as well as being the youngest.

She states that the biggest change since then has been the increased ‘visibility of the conversation around philanthropy,’ with ‘more knowledge, learning, academic work, and work on best practice’ available. Organisations such as New Philanthropy Capital, which is a think tank for the philanthropy sector, are pushing the agenda of evidence-based impact measurement.

Fran also noted the recent growth of donor-advised funds which ‘don’t increase transparency’. Another trend is that participatory grantmaking and lived experience are becoming a larger part of the conversation, but are often ‘much harder to measure or catch in data.’

She also discussed her passion for data, which led to her founding 360Giving, which is a data standard developed in the UK. In the last 6 years, 360Giving has had ‘196 foundations sharing 108 billion pounds worth of data in a common standard’ which can be searched online. All of the code is published openly so that it can be used by other countries or organisations. The aim of 360Giving is to cut back on the ‘waste and inefficiency that donors and charities experience here’ while ‘increasing our ability to evaluate what we do.’ Fran hopes that in the future ‘knowledge infrastructure is something we prioritise’ as it will better ‘enable collaboration.’

In response to a question from Keidan about the effects of Brexit, Perrin emphasized the need for continued collaboration between the UK and other European countries, and how philanthropy is privileged as it’s not ‘dependent on government actions to allow our work to happen.’ She focused on the need for cross-border collaboration, knowledge sharing and learning, particularly through ‘real-time data.’

Panel Q&A

Keidan started off asking if the panellists thought that the sector’s collective action to address climate change is insufficient.

Dimovska stated that more needs to be done, arguing for a more ‘nuanced understanding of the role of philanthropy in terms of advancing the climate conversation’ while taking a more ‘holistic view’ of how the activities of foundations are addressing the challenge. Anna added that, from a Polish perspective, the biggest issue is government, and there is a role for philanthropy to ‘create pressure on government’ to enact more policies that address the crisis.

Keidan’s next question was around addressing the lack of diversity in the sector. Perrin answered by saying that although the diversity conversation is happening more often, ‘many foundations aren’t engaging with it properly.’ Transparency around lack of diversity is helpful, but doesn’t solve the problem alone as public opinion doesn’t necessarily impact their work. She would like to see more donor-to-donor peer pressure to say ‘this is 2021, this needs to change and it’s possible.’

Sienicka picked up on the conversation around participatory grant-making, which was discussed during the EFC conference. Participatory grant-making could be an answer to diversifying decision-makers and making the process more inclusive by bringing in communities and giving them a voice.

Keidan then took a question from the audience. Matteo Bottecchia asked: ‘how does the need for evidence about what works intersect with funding decisions? Do you have a sense that more and more funding will be directed towards beneficiaries and organizations that can measure (and demonstrate) their impact?’

Perrin responded by saying that while both the impact-based and trust-based movements have merit, ‘both tend to be applied over-simplistically… it’s seen as one or the other’ when often different models are better suited to different situations. This is where participatory grant-making may be able to offer solutions. ‘Can we have a trust-based relationship but let charities and communities set the quantitative measure they want to see change on?’ Perrin asked. ‘There’s no reason these can’t be intertwined but the debates have happened in two very different silos, and I haven’t seen enough work done to bring them together yet.’

Dimovska agreed with Perrin’s comments and added that there is a great need to understand ‘what forms of philanthropy are appropriate to the kinds of challenges we’re trying to address, and what kinds of methods and tools for measuring impact should we use?’ She mentioned that there is scope for intermediaries in this space to facilitate this ongoing conversation.

Conclusion

To wrap up, Moralis offered closing remarks on the discussion, summarizing some of the key points:

- The importance of building knowledge and allowing space for failure, and for learning from failure

- The need to contribute to sustaining and bolstering democracies.

- Stimulating creativity and creative learning to foster innovation in the sector

- Focusing on action rather than despair in the context of the climate crisis

- Remembering that ‘responses and solutions are not black and white’ and working to further diversify the sector and make it more inclusive

Moralis mentioned how concerns around funding gaps during the Covid-19 crisis were a key theme during the EFC conference. However, a survey of EFC conference delegates also found that they were hopeful that the pandemic would be an opportunity to ‘reset the system, to review foundation practices and look at it through an intersectional lens so that we become more engaged, more vocal, more inclusive, more visible, more responsive and more collaborative.’

She finished by reiterating the three words that she hopes will shape the future of European philanthropy: ‘courageous, inclusive and humble.’

This event was part of our ‘future of philanthropy’ webinar series celebrating Alliance’s 25th anniversary. The next event in the series will explore the future of Asian philanthropy. You can register for it here.

Annmarie McQueen is the Marketing, Advertising, and Events Manager at Alliance.

Watch a recording of the webinar below:

Comments (0)