Many funders are reluctant to delve into legal work because they see it as too specialised. However, it can be a more supple and accessible instrument for achieving change than they realise

To a degree unprecedented in the lifetimes of most of us, 2020 saw government intervention in the lives of citizens with legislation and policy changing at speeds unimaginable before the pandemic. It provided a forcible reminder to many of us working in philanthropy that now, more than ever, our work often sits at the intersection of state and citizen. In a world of growing inequality, attacks on the rule of law and deep uncertainty, we are excited to examine legal action as a key tool for interrogating and challenging power and advancing justice.

Public opinion is a powerful advocate. Photo: Mihai Surd

However, courtroom judgments are only part of the solution. Many funders have moved beyond strategies that focus solely on the single big win. What follows is a more complex and – we think – far richer analysis of how legal action at its best is long-term, rooted in community movements and often taking place a long way from the rarefied atmosphere of the courtroom.

A call to funders

From the various contributions to this special feature and from our own experience working for foundations in South Africa and the UK at the intersection of law and philanthropy, we urge funders to:

- recognise that there is a wide range of legal strategies that can be supported by foundations. No matter what issue area we are working on, the law probably touches on that issue area and can be a means of furthering it

- support experts and the building of expertise in this field, from paralegals to strategic litigators to community organising

- support the institutions of democracy including the independence of the judiciary and a robust civil society sector. These institutions are essential to protect, promote and fulfil the rule of law and rights

- reassess the notion of results and ‘wins’ and ‘losses’ – a loss in court can still mobilise a campaign to change hearts and minds

- stay in it for long haul – change takes time

- protect the defenders of human rights who often place their own lives at risk in doing this work.

So what’s stopping us?

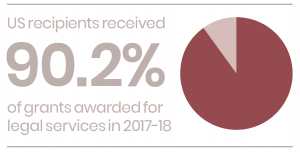

We know that funding for legal action remains too little and too concentrated among a handful of committed funders or on very specific, often siloed, issues. In 2017-18, only seven funders made grants in excess of $10 million for litigation according to data from Candid. Fifty per cent of the top 100 funders of litigation made grants of $1 million or less. Of the almost $350 million spent on law education in 2017-18, only 11 per cent was spent outside the US and only 1.8 per cent went to non-US based recipients.

Our experience is also that many funders find this work daunting, believing that it requires legal knowledge or new grantmaking practices. As so many of us refocus our efforts on how to better listen to the communities we serve, the specialised work of legal action and legal strategies may seem to smack of elitism.

This edition will challenge those misconceptions. It does not offer a silver bullet, but it highlights the fact that civil society is using legal action to do urgent and effective work and it needs the backing of philanthropy. The entry points exist for all of us and they are more familiar than we think: long-term funding, core support and people-centred strategies.

Strategic litigation… must be used as a tool by and for strong and resilient movements and sit alongside work for social progress.

And, yes, the risks are familiar also: backlash, unintended consequences and messy movement building, but if you do any social change work, you will have navigated these before.

More than strategic litigation

More than strategic litigation

This special feature also reflects the wide range of activities and strategies involved in legal action and explores the unique contributions of many foundations and organisations in this field in their quest to advance justice.

Ultimately, law is a tool that crosses boundaries and can be an excellent means of building transnational solidarity.

Atlantic Philanthropies and Open Society Foundations reflect on more than a quarter of a century of strategic litigation to defend and advance human rights, and combat torture and inhuman treatment. The work of their partners to give South Africans access to anti-retrovirals to fight HIV and to advance digital democracy in Kenya are all critical markers that tell a powerful story of how the law can serve the ends of justice. They also reflect on how the law can be used and misappropriated by authoritarian leaders to consolidate control and suppress dissent and why now more than ever the role of human rights lawyers, strategic litigators and funders willing to fund this work is so critical.

By presenting these and other cases, we hope to better equip readers with an analysis of the accomplishments of philanthropy as well as the ongoing challenges that we may need to grapple with in 2021 and beyond. We also look back at some of the literature that informs our practice.

Community paralegal consultation in Rwanda. Photo: Legal Aid Forum

Funding people-centred justice

Lorenzo Wakefield from the Mott Foundation highlights people-centred justice and the role of the paralegal infrastructure across Africa – an often neglected area of funding. The Mott Foundation’s experience shows that work at local community level by paralegals, far away from the highest apex courts of a country, are just as critical to advancing justice for poor communities and levelling the playing field in terms of access to justice. He makes a plea for financing people-centered justice at community level, recognising that justice may take many forms. This requires more innovative and creative thinking by foundations so that they fund work in a way that does not fuel competition for resources and builds on a broader global movement for people-centered justice where law is recognised as one of the many powerful tools for change.

Jackson Otieno from UHAI EASHRI reminds us that, even when strategic litigation has a role to play, it is rarely an end in itself. It must be used as a tool by and for strong and resilient movements and sit alongside work for social progress. UHAI has been working for sexual and gender minorities in East Africa for over a decade and has funded litigation to decriminalise same sex conduct and to push back against efforts to legislate away the rights of LGBTI people. At the heart of this work are the communities themselves.

Building alliances, building capacity

In a similar vein, Aleyamma Mathew points out the interconnected movements for change and alliances that we need to support to truly uphold the rule of law and democracy – from activists and organisers to policy advocates. She flags and celebrates the important work of #MeToo movements in ensuring that perpetrators of sexual harassment are held accountable in the court of public opinion as well as courts of law. Like so many of our contributors, Mathew highlights that litigation is one component of a legal strategy and that advancing law and social change should never mean funding only lawyers but rather considering the role of a wide range of actors. In the feminist movement, this means considering the role of survivors, community mobilisation, policy advocacy and research as all critical to advancing social change.

Many of the authors in this special feature remind us that legal action takes time and funders need to invest over the long term and make the connections from local to global and global to local.

This ecosystem approach is useful since it allows foundations to consider the role that law plays in a range of thematic and issue areas that we all work on, be it healthcare, human rights, technology, women’s rights or migration – the role of law as a tool to fight systematic oppression across a range of areas is worthy of more in-depth analysis and funding.

Nick Grono from the Freedom Fund demonstrates that these themes of effective legal action are also relevant to their work to challenge the actions of the corporate sector in the fight against modern slavery. Alongside an active strategic litigation programme, the Freedom Fund is developing the capacity of organisations in the Global South to undertake investigations as the core of a sustainable ecosystem for this work that builds bridges between organisations in the Global South and Global North.

Connecting the local and the global

Ultimately, law is a tool that crosses boundaries and can be an excellent means of building transnational solidarity from South Africa to the US, Ireland, the UK and Germany. Romy Krämer highlights the pressing issue of closing civic space in Germany, an issue that will resonate for many of us in other jurisdictions. In the UK, access to justice and closing civic space have become directly intertwined as the government reviews both the system of administrative law and the Human Rights Act. These local examples of a global phenomenon also highlight that progress in this space – like much social change – can also produce a backlash. Many of the authors in this special feature remind us that legal action takes time and funders need to invest over the long term and make the connections from local to global and global to local.

We know that the law cannot change the world by itself and no one in this special feature is offering a romanticised vision of how the law or litigation and legal action can solve all the world’s problems. But we do want to emphasise that these tools are critical in terms of incremental and systemic change. For funders of all kinds, there are numerous pathways available to support this work. For some, this will mean direct financing for strategic litigation; for many, it could simply mean core or project funding for organisations working to advance justice and the rule of law at community level, movement level or within the courts by lawyers.

We know that the law cannot change the world by itself and no one in this special feature is offering a romanticised vision of how the law or litigation and legal action can solve all the world’s problems. But we do want to emphasise that these tools are critical in terms of incremental and systemic change. For funders of all kinds, there are numerous pathways available to support this work. For some, this will mean direct financing for strategic litigation; for many, it could simply mean core or project funding for organisations working to advance justice and the rule of law at community level, movement level or within the courts by lawyers.

As guest editors, we feel privileged to have learned from all the extraordinary contributors to this special feature. Our hope is that their insights will cause readers to reflect on legal action in your own work, because funders of all kinds have a role to play in this ecosystem. We recognise that funders often struggle with entry points to legal action – there is no right approach – but we do think that the diversity of activity in this area makes it more accessible than ever.

All of us working in philanthropy can and should question whether our funding supports the communities we serve. We should aim to see what justice looks like for them, within their context, and help people make their own, informed decisions on legal action. This may involve re-imagining justice and how the law interacts with communities most in need. It may well involve challenging power at a range of levels within society. In the end, it will be their knowledge, courage and leadership that will create lasting social change and this requires philanthropy to be bold in its approaches and generous in its support.

Nicolette Naylor is international program director of Gender, Racial and Ethnic Justice; director Southern Africa at Ford Foundation.

Email: n.naylor@fordfoundation.org

Twitter: @NaylorNikki

David Sampson is deputy director at Baring Foundation.

Email: david.sampson@ing.com

Twitter: @davidnsampson

Comments (0)