Guatemala is among the 19 most diverse countries on the planet. Its particular vulnerability to hurricanes, tornados and drought makes it urgent and critical to respond appropriately to the threat of climate change. However, any response must be grounded in respect for human rights. It must be committed to the full, equal and effective participation of those most affected but contributing the least to climate change – indigenous peoples.

Climate change is affecting our communities not only through the natural disasters that are its by-products, but through mega-development projects. As part of Guatemala’s Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs), mitigation strategies are moving away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy. However, as an example, the development of the hydroelectric dam, Hidro Santa Cruz in Huehuetenango, has become a source of contention. The proposed project would be installed in an area used by the Q’anjob’al people for ceremonial, recreational and agricultural purposes.[1] The community was not consulted about the project and did not consent to its construction. Community leaders, ancestral authorities and spiritual elders who question proposed development projects are met with threats, criminalization and persecution. Some have been killed.

‘The development of the hydroelectric dam, Hidro Santa Cruz in Huehuetenango, has become a source of contention. The community was not consulted about the project and did not consent to its construction.’

In the department of Huehuetenango, one indigenous group, Asociación de Mujeres Eulalenses para el Desarrollo Integral Pixan Konob, has received philanthropic support for their work on reforestation, traditional seeds and native plant species, and natural resource management. They have also worked to integrate women’s rights, political participation and leadership development. This backing of traditional knowledge as part of the climate change solution is a positive step. However, what is missing is direct funding to traditional authorities and autonomous organizations. As these are often based on traditional structures, many have difficulties in receiving direct funding because they are not NGOs.

‘What is missing is direct funding to traditional authorities and autonomous organizations.’

Philanthropists must work directly with our knowledge holders. They are the keepers of a vision of life and the world grounded in the interconnection between humanity and all the sacred elements. This has conserved our rivers, forests, traditional seeds and medicines. Indigenous youth are looking to learn these traditional teachings from elders not taught in western-based educational systems. Support for intergenerational knowledge exchange is one of the things most needed from philanthropy. This includes native language revitalization and spiritual formation which in turn will strengthen our social institutions.

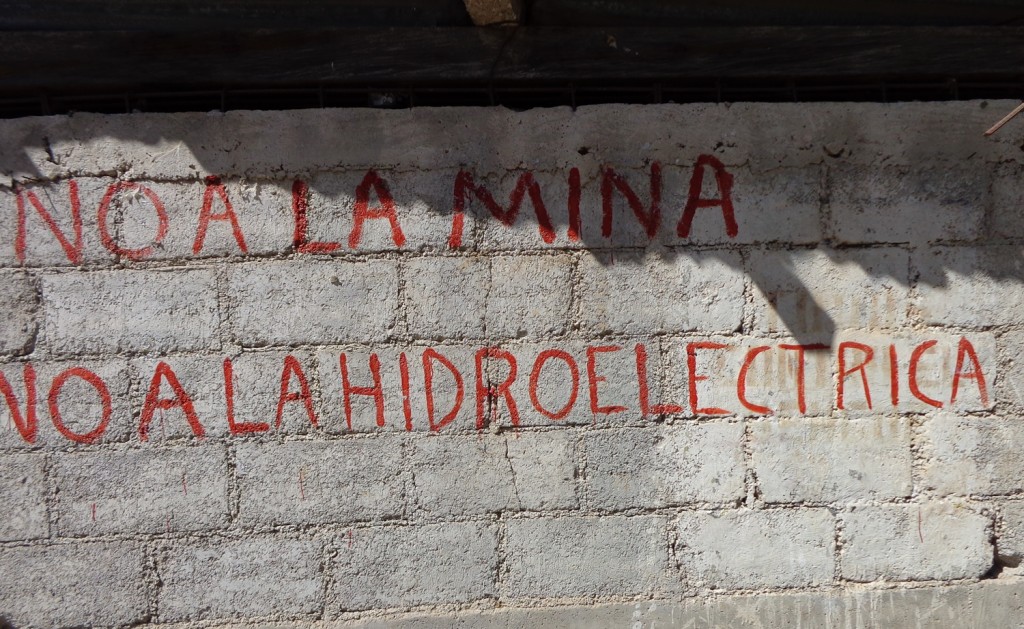

Graffiti in Pavencul, Chiapas, Mexico stating ‘No to Mining, No to Hydroelectric’. Credit: Arturo Cabrera, International Mayan League.

Information sharing is critical in our communities yet internet access remains a luxury. Our youth are technology-savvy and need basic equipment from computers to generators so that they can stay informed and connected and can facilitate the participation of their elders in processes affecting their peoples. Part of the problem is that many in our communities are not aware of these processes because information does not reach them. Equally, philanthropists should consider funding indigenous media platforms such as community radio programmes, journalists and photographers.

The philanthropic community must also support efforts to give indigenous governments a more appropriate status within the UN system.[2] Climate change-related meetings at the UN or the World Bank need to ensure that traditional authorities from indigenous peoples are included.

‘We are pushing for a power shift that allows indigenous peoples to make decisions over processes affecting our lands, territories and natural resources.’

We are pushing for a power shift that allows indigenous peoples to make decisions over processes affecting our lands, territories and natural resources. We are asking that our knowledge systems be valued and integrated into climate discourse, policy development and actions. Those knowledge systems, of which elders, spiritual leaders and ancestral authorities are the custodians, are key to relearning how to care for the earth.

Juanita Cabrera Lopez is executive director of the International Mayan League/USA. Email juanita@mayanleague.org

Footnotes

- ^ Cultural Survival, ‘Guatemala: We Are All Barillas – Stop a Dam on Our Sacred River!’ http://tinyurl.com/StopDam

- ^ Indian Law Resource Center, ‘Oklahoma tribes learn about engaging in the UN system’: http://tinyurl.com/EngagingUN

Comments (0)