Following my first exposure to community philanthropy at the Global Summit in December 2016, I left feeling both excited and challenged. Community philanthropy – I learnt at the conference – believes in the process as much as the output, prioritizing building and delivering projects with communities, and being adaptable.

‘Participatory’, ‘inclusive’, ‘community-based’, ‘localisation’, ‘partnership’, amongst other phrases, were all used with genuine passion and enthusiasm. These terms are also widely used by international, national NGOs and donors, who are historically seen as the more ‘traditional’ international development organisations. So it seems logical to question how community philanthropy intersects with the ‘traditional’ international development field?

Seven points of intersection raised by conference attendees are listed below; they provide no clear answers, and may provoke further questions, but outline areas for thought and debate.

Seven points of intersection raised by conference attendees are listed below; they provide no clear answers, and may provoke further questions, but outline areas for thought and debate.

A word of warning!

Throughout the discussions below it is important to recognize that both areas of work are dynamic, already infused in some places, and that each individual organisation or entity needs to be judged by its own merit. The blog tries to avoid – albeit not wholly successfully! – sweeping analysis of particular types of organisations (e.g. community foundations vs INGOS) in an effort to circumvent a traditional binary development approach and to recognize the diverse actors that now operate within the development sector as a whole.

- Common narrative

There is a common vision and narrative across both fields of work about societal resilience, linking eco systems and prioritising local responses and community interests. There is also general understanding that the current way of working by ‘traditional’ international development actors is out dated: ‘Everyone recognises that the system is broken but individual organisations don’t have the power to change that’ (participant). While there is a natural link between these two areas of work there are also a number of contradictions related to their connection (e.g. international vs local, top-down vs bottom-up, donor-led vs community-led etc.), which may sit uncomfortably with some actors. - Realigning roles in line with shared ideas

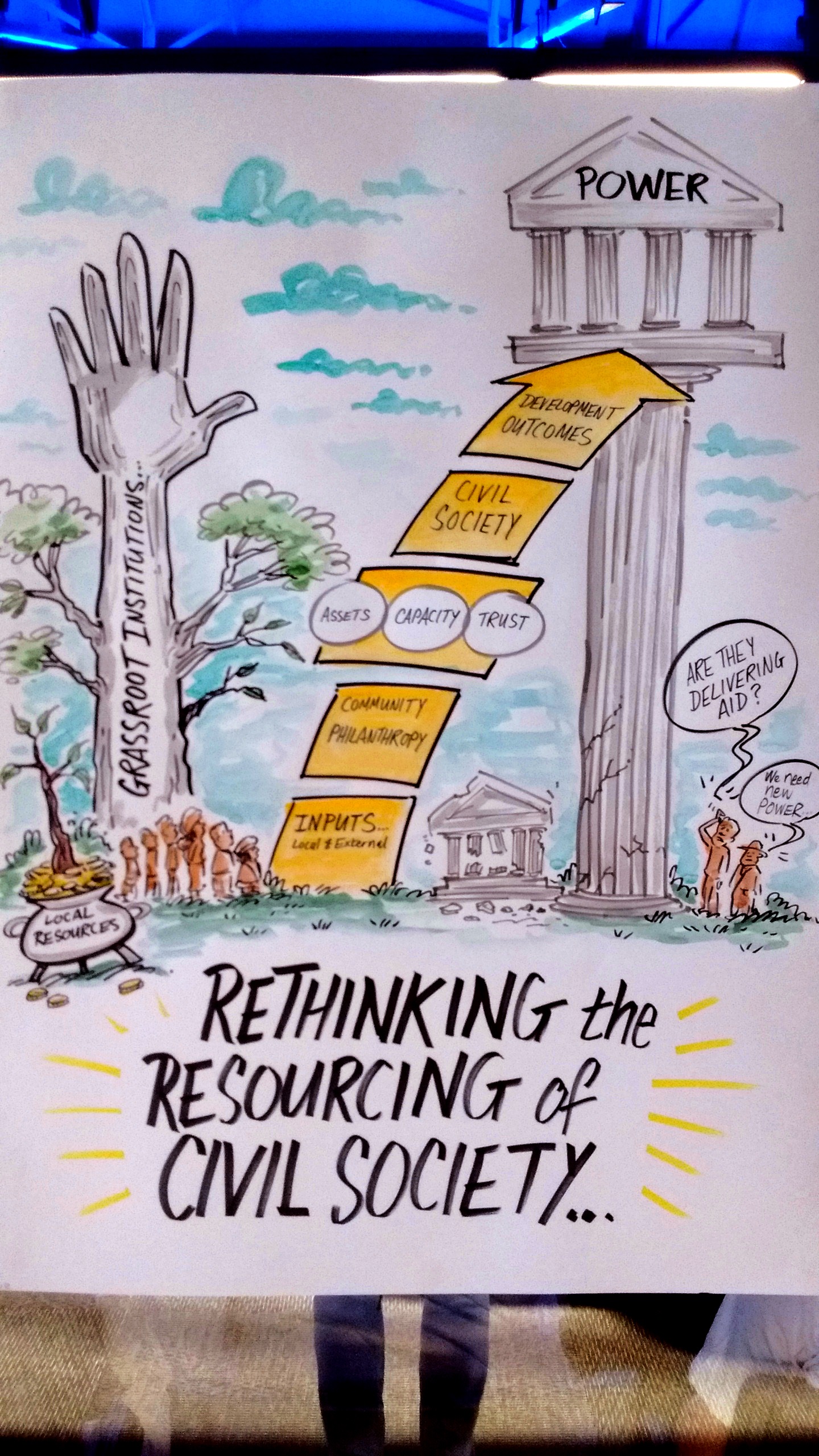

Historically, power has been held by donors rather than the ‘target’ communities and local organisations. For example, the multi layered NGO-CSO structure (where funds are passed from donor to NGO to community-based agency) was described by participants as not always being ‘an empowering power’; it is broadly recognized that ‘traditional’ aid actors ‘can’t keep doing the same thing in the same way and claim [to be] shifting the power’ (participant).The legitimacy of Southern and local actors, the value of different types of capacities and assets – e.g. local knowledge, language, relationships, time, people etc. – and of seeing communities as agents of change themselves, is widely documented as key for successful development. Roles are starting to change accordingly and through INGO decentralisation and localisation, and innovative initiatives like the START Network, ‘traditional’ development actors are starting to take uncomfortable (but necessary) steps towards surrendering control of funds, responsibility and its associated power.With the parallel growth of community philanthropy, it is clear that the space for and authenticity of smaller community organisations needs to be protected. To remain strong, community philanthropists must retain their independence and not compromise their agility to the lure of extra funding or other influences: to continue to be effective and genuine “community philanthropy can’t be swallowed by larger organisations, it has to remain small” (participant). - Breaking down the silos and changing together

Working as separate sectors, yet with the same vision and within the same development space seems counter-productive. By community philanthropy actors and traditional aid actors attending joint conferences and engaging with each other, both fields can share and learn from complementary but different experiences. - Initiating joint collective management

Many believe that there is more power – and sustainability – in having multiple local advisors who create a shared vision for working together and a set of common rules about how to deliver work and control a resource collectively. In some instances ‘traditional’ development actors are creating the space and providing initial resources (e.g. funding, information, advice) for this, whilst community philanthropists can provide the access and process to get the funds to communities. See the START Network for more information. - Helping ease the connection between long-term development and disaster relief

With increasing numbers of protracted crises across the globe, a seamless link between long-term development and disaster relief is sought after. Crises can be seen as opportunities to address structural problems. With the sharp spike and then relatively rapid reduction in resources, community philanthropy is starting to provide a fitting exit strategy for the humanitarian aid system, as well as suitable infrastructure for development actors to invest in before crises to help strengthen resilience. - Investing in local CSOs

Southern CSOs need to be supported and strengthened so that they can start galvanising money from the global South, donors and national governments. Where necessary, ‘traditional’ development actors can help build capacity. Valuing existing capacities (e.g. local knowledge and relationships, safe project delivery etc.) is critical, as is investing (with untied funds) in building strong institutions, training and financial software.Being able to fulfil the various due diligence requirements is fundamental for Southern agencies. Capacity support on decision-making, collective management and project management (including risk analysis and adaptation), were also identified as valuable. See the NEAR Network for more information. - What about the donors?

Many international and national organisations are tied by donor priorities, rules and guidelines; civil servants need to know where money is going to ensure that they are accountable to their respective publics and their interests. This can be contradictory to the organic and flexible approach of community philanthropy. Some feel that INGOs need to challenge donors, and at the same time be more critical of their own positioning as the “middle man”, to help enable fluid funding and a real shift of power.

The complementarities can’t go unnoticed; if changes continue to happen in line with the joint rhetoric, and responsibility and power become more shared, an alliance of some sort between ‘traditional’ development agencies and community philanthropy could be a positive thing.

Yet for the status quo to change, actors need courage, experience and imagination to think beyond the known structures and systems and reimagine their roles; they would need to find opportunities for change and to experiment with new ways of working.

It is also clear that any connection in practice would be difficult and complicated; changes need to be made slowly, sensitively, based on mutual interest, and with care to avoid community philanthropy becoming commercialized.

And for the dance? ‘Traditional’ development actors, I assume, would jump onto the dance floor, but those in community philanthropy may be more cautious and hold off until the ideal song arrives.

Anna Wansbrough-Jones is a consultant and Director of Stratagem International based in Johannesburg.

Photo credit: Gerhard Cruywagen of Greenhouse Cartoons.

Comments (0)