If it is to play its part in tackling climate change, philanthropy itself needs to change – and it needs to do so immediately

Climate change has emerged as the greatest challenge of our time. Its impacts are clearly visible, with more frequent extreme weather events and their effects around the world. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) reported a record 22 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters across the US in 2020. In 2019, Mozambique and neighbouring countries were devastated by cyclone Idai, and again by tropical storm Chalane in late 2020.

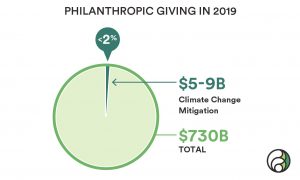

Graphics and data by ClimateWorks Foundation as published in ‘Funding trends: Climate change mitigation philanthropy’ (September 2020)

It is estimated that Kenya will experience mean temperature increases of up to 1.5 degrees by 2030, exacerbating the droughts and floods from which the country is already suffering, escalating food insecurity and causing loss of life, livestock and biodiversity. Sea-level rise is also an ever-present concern in Kenya, forcing people further inland while at the same time escalating scarcity of potable water as a result of saltwater intrusion into fresh water sources.

The Covid-19 pandemic has hardest hit many of the communities that were already affected by climate change, with lockdowns and restrictions of movement and their subsequent consequences for people’s livelihoods. This has brought calls for action to increase the focus on climate justice and amplify a green post-Covid-19 recovery – to ‘build back better’. Last year’s estimated 7 per cent fall in global emissions created by Covid restrictions is set to be short-lived, and according to some sources they have already more than rebounded.

The pandemic has shown us very clearly that we need to re-think how we live, work, eat, move and produce energy and that climate action has to be integrated into a wider response to disasters be they health or climate-induced. To date, we are nowhere near on track to keep global warming within the 1.5°C agreed in the 2015 Paris Climate Accord. In fact, current policies by national governments would lead to a global mean temperature increase of at least 2.93°C by 2100, making our present form of life impossible.

Philanthropy’s response – must do better

Despite the starkness of this situation, addressing the climate crisis is not yet a priority among philanthropists. In 2019, less than 2 per cent of philanthropic giving was spent on tackling the climate crisis.

Clearly, this needs to change and this issue of Alliance highlights some of the ways in which funders are setting examples others might follow. As Sandrine Dixson-Declève points out, the Covid pandemic has highlighted the convergence of environmental and human health tipping points. In order to ‘emerge’ from this emergency, as she puts it, ‘with a new holistic vision for building resilience to future shocks and enhancing human well-being, speed and scale are key’.

Philanthropy also needs to support grassroots action for climate justice but it needs to trust that communities themselves know best and already possess resilience.

Funders could play an important role in designing this transformational change, as Dixson-Declève notes, and 2021 provides many opportunities for action, from the Conference on Biodiversity (COP15) in China to the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow in November. Isaiah Toroitich points out the climate justice movements’ important role of ‘building a comprehensive understanding of climate change’, thus such movements need to be more deliberately financed.

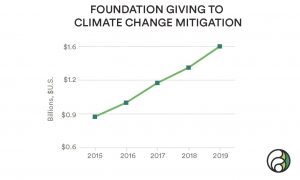

Graphics and data by ClimateWorks Foundation as published in ‘Funding trends: Climate change mitigation philanthropy’ (September 2020)

Although it is late in the day, as Richard Black argues, solving climate change is still within reach. It needs relatively few people in key positions, he suggests, but we need to tell ‘the right stories to the right people’, and make accelerating decarbonisation part of the political narrative in enough countries. Philanthropy, Black emphasises, has supported this kind of strategic communication in the past, and has been successful notably in making the UK embrace the national net zero target a lot more ambitiously.

The power of creating a new narrative, of connecting with the climate crisis in more visceral ways is also underlined by acclaimed artist Olafur Eliasson. Eliasson describes how art and its power to create new narratives and visuals can resonate with us and create visions of a future that lead to action. He shows us that to tackle the climate crisis, we need to connect hearts, hands and minds. This and other vignettes from the front-lines of climate change in the Arctic and Antarctica demonstrate that connecting to climate on a deep personal level can create a mindshift that moves us to act – if only we are willing to listen and to be touched.

Philanthropy’s way forward

We suggest that these three considerations are key to shaping philanthropy’s response:

- The climate crisis can no longer be treated as separate from other funding areas. Neglecting climate risks might undermine the success of your giving elsewhere. As Sonia Medina discusses, funders such as the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, which started off with a focus on improving the lives of children in developing countries and have added climate change to their portfolio, exemplify how some funders have started to re-think their work in light of the climate crisis.

- Even if a foundation finds it difficult to include a climate angle in its philanthropy, it can reduce emissions by changing how it operates, especially by looking at its investment portfolio. As Nando van Kleeff from the IKEA Foundation shows, integrating climate risks into investment portfolios can be a powerful way for funders to help combat the climate crisis.

- We cannot leave the task of acting on climate to the handful of big donors who have been instrumental in establishing the field of climate philanthropy. Every contribution counts, no matter which topic or which approach is being supported. The most important step is to get started. As Nigel Topping, the UK’s High-Level Champion for Climate Action, points out, there are many opportunities to build on existing knowledge, expertise and infrastructure.

Supporting the levers of change

As a climate philanthropist, you can focus on specific sectors, such as energy and transport, manufacturing, construction or farming and food production. Another approach is a regional one, funding projects in regions that are hit particularly hard by the climate crisis – such as coastal areas facing increased flooding or regions affected by ever more intense heatwaves, with resulting crop failures and knock-on effects like ill-health, hunger, poverty and migration.

Another area for potential support is specific levers of change. Policy change and advocacy, education, strategic communications, public campaigns, litigation initiatives, movement and coalition building – all these are vital to raising awareness about the urgent need for climate action and to mobilise communities as well as economic and political decision-makers.

Philanthropy must become more participatory, more inclusive and more driven by the communities it is trying to support. Tackling the climate emergency is a task that involves nothing less than reinventing the way we live and the way we work.

Philanthropy also needs to support grassroots action for climate justice but it needs to trust that communities themselves know best and already possess resilience. This sort of partnership should be light on bureaucracy and complicated reporting and monitoring procedures. These are not only time-consuming but also often exclude Indigenous groups, young people and those with disabilities who may not have the skills or capacity to fulfil the required criteria. In fact, funding should focus precisely on innovative non-traditional initiatives to tackle climate change led by these groups to ensure that they do not continue to disproportionately bear the impact of climate change.

Aftermath of Cyclone Idai. Credit: Climate centre/Flickr

Support may include intergenerational knowledge exchanges, traditional climate adaptation measures or art forms such as neighbourhood murals, festivals, songs, podcasts, TikTok videos to help advance climate advocacy and campaigns. The resourcing playbook specifically dedicated to youth-led groups and movements outlines some key recommendations for philanthropists, with an emphasis on listening more and forging partnerships. It is also worth remembering the power that philanthropy has in terms of framing funding agendas especially for the ‘large traditional’ foundations whose decisions many smaller ones seem to follow.

Climate justice can also be supported by funding relatively new and hitherto overlooked approaches, such as litigation. In 2018, a group of young people sued the Colombian government for the protection of the Amazon, arguing that continued deforestation was in contravention of the government’s own climate targets, and therefore infringed their rights. They won at appeal in a landmark ruling that also establishes that the Amazon has ‘rights’. Funding such ligation is important to secure not only the future of generations to come, but also to establish that nature in itself should be protected. Funding litigation can help ensure that governments and other actors are held accountable for their climate targets.

Low-lying islands such as Fiji are facing the full force of climate change. Credit: denisbin/Flickr

What’s at stake at COP26?

And so to Glasgow. One of the key areas for deliberation at COP26, which would also significantly advance climate justice, is the issue of ‘loss and damage’. This is a topic whose progress has for years been hampered by fears of liability claims and compensation by developed countries and thus no agreement on its funding has been reached. The climate justice question remains: how do we ensure that communities already being afflicted by loss and damage are able to be resettled or compensated? And how do we handle the increasing phenomenon of climate refugees arising from loss and damage?

According to a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR5), some small islands and low-lying areas in the Pacific, Asia, Africa and elsewhere will be completely submerged by the end of the 21st century. The world cannot continue to ignore this, especially as the small island states have contributed least to climate change. Efforts to address resilience have come in the form of the race to resilience initiative in which the philanthropic world and other non-state actors are taking leading roles. Yet it is imperative that governments step up, since this is an issue which requires resources beyond the reach of non-state actors alone.

We are not the first generation to have realised what’s at stake, but the last one to be able to provide a tomorrow that is resilient, just and peaceful.

It is also expected that countries will translate commitments contained in their updated national climate plans, the nationally determined contributions or NDCs, into action. But with finance playing a key role in making the needed transformation a reality, COP26 needs to see more commitments not just from governments but also from the philanthropic world, like the Funder Commitment on Climate Change, launched in the UK at the end of 2019.

Climate leadership, climate justice

Ultimately, climate leadership is about climate justice. With this special feature, we seek to raise awareness, to inspire, and to provide guidance on how funders can make climate justice central to their efforts, and in doing so fulfil their role as stewards of the future. In order to ensure that those who are disproportionately affected by climate change have access to resources, capacity and technology to cope with the impacts, we need a new form of collaboration. Philanthropy must become more participatory, more inclusive and more driven by the communities it is trying to support. Tackling the climate emergency is a task that involves nothing less than reinventing the way we live and the way we work. For the young generation this process has sometimes started with an experience of grief and loss, the concept of solastalgia, or homesickness in a dying world, that has been described by the Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht. However, it is also the younger generation, and those most affected by the impacts of climate change, who have shown courage and optimism, an amazing resilience and ability to adapt. That is a powerful basis to build on.

We are not the first generation to have realised what’s at stake, but the last one to be able to provide a tomorrow that is resilient, just and peaceful. We have much to lose, but a lot more to gain. Equipped with the impressions of this issue, it’s ultimately up to each one of us to identify our role in shaping the future. The next decade will be decisive. As Sonia Medina of the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation puts it: ‘Let’s hope we’re not looking back and asking why we didn’t do more when we could.’

Felicitas von Peter is founder, Active Philanthropy.

Email: vonpeter@activephilanthropy.org

Twitter: @ActPhilanthropy

Winnie Asiti is a member of the Next Generation Climate Board, Global Greengrants Fund and an adaptation strategies analyst, Climate Analytics.

Email: w_asiti@yahoo.com

Twitter: @asiti

Comments (0)