Four first-hand accounts that give powerful testament to the impact of climate change on the polar ice sheets

The scientist

The scientist

Julienne Stroeve, research chair in Climate Forcing of Sea Ice at the University of Manitoba

During winter 2019-20 I had my first opportunity to experience the Arctic during the polar winter. I was part of the second leg of the MOSAiC year-long Arctic drift expedition, drifting with the sea ice during the dark period. I arrived at Polarstern on 13 December, excited to start collecting valuable data that would help us improve our ability to map sea ice thickness from satellites, and better understand the drivers and implications of rapid climate change in the Arctic Ocean.

The first step out on the ice was surreal… it felt as if I was walking on the moon. The bitter cold snow crunched loudly under the weight of my footsteps, and the only light was that which my headlights made, and the ship in the distance. I would call this ice floe my home for the next three-and-a-half months and while delays in changing over the crew meant I was to be gone a full month longer than anticipated, I was fortunate to stay long enough to see the light come back to the floe. The one thing that surprised me was how mobile the ice was… I expected the ice to be relatively thick, and yet every time we had high winds, we would have leads opening up that threatened installations or ridges that would destroy equipment.

A more dynamic ice pack is expected as the ice cover continues to thin in response to a warming Arctic. The Arctic sea ice has been shrinking in size and thickness over the last several decades, resulting in about 50 per cent more open water at the end of summer than observed in the 1970s. Since ice loss is strongly linked to warming from atmospheric greenhouse gases, scientists estimate that the Arctic Ocean will become ice free in summer by the middle of this century if we continue business as usual.

The artist

The artist

Olafur Eliasson, founder of Little Sun, and UNDP Goodwill Ambassador for Climate Action and Sustainable Energy

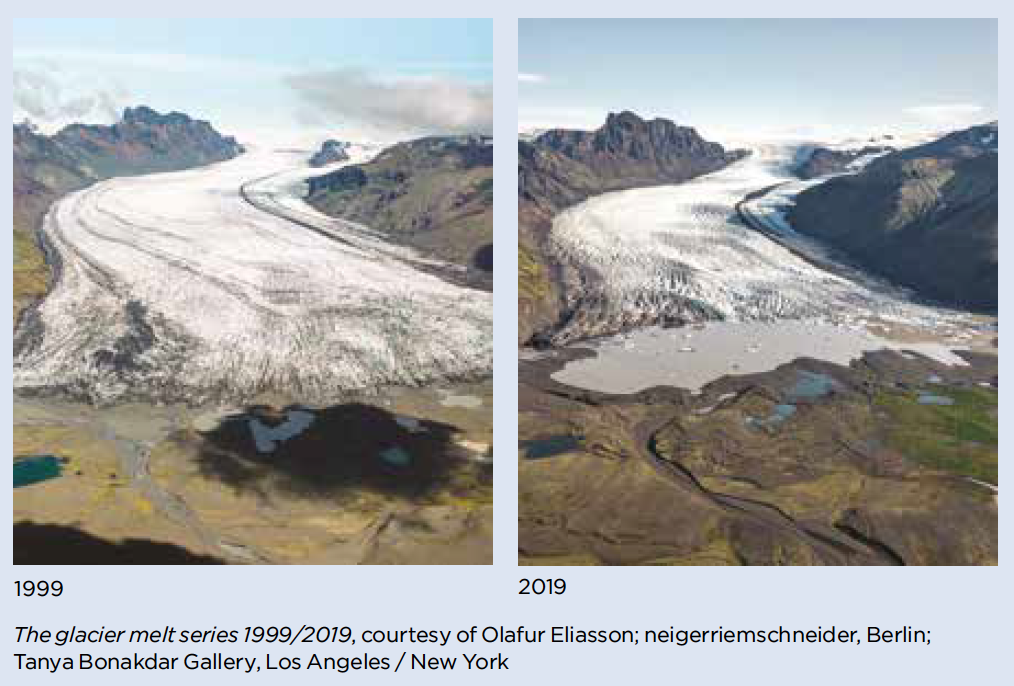

The first time I flew over a number of Iceland’s glaciers to photograph them from the air, in 1999, they struck me as majestic and seemingly immutable. At the time, I took the natural environment for granted. Twenty years later, in the summer of 2019, I went back to the same locations to photograph the glaciers again, from the same angle and at the same distance. In the resulting photographic pairs, which form The glacier melt series 1999/2019, it is shocking to see the difference. All of the glaciers have shrunk considerably.

We humans respond better to narratives, to what affects us directly and emotionally, than we do to data. This was the idea behind Ice Watch, an artwork that I conceived with geologist Minik Rosing, where I brought enormous blocks of Greenlandic glacial ice to cities around Europe and left them to melt in public space. Putting your ear up to the glaciers, you could hear the crackling sound of ancient bubbles popping, releasing air that had been frozen inside the ice for thousands of years. In those bubbles, you could hear the climate from before the Anthropocene, before the carbon-hungry activities of large corporations and the citizens of industrialised countries had jeopardised earth as a liveable space for us all.

Today, we hardly have to work to make climate change tangible – we have witnessed some severe effects, in yearly wild fires, more intense storms, droughts, and polar vortices. But I see great potential in working with narratives and visuals that elicit identification and a feeling of proximity to propose hopeful visions of the future that will motivate the action, local and international, to mould a tomorrow that will still afford humans liveable and peaceful lives.

To do this, we must listen not only to ourselves, but to the voices of the younger generation, who will be forced to respond to the problems that we have allowed to go unanswered for so long. With my artwork Earth Speakr, created on the occasion of the German presidency of the European Council in 2020, I reached out to young people and to children to find out what they consider important. In the form of a playful app, Earth Speakr invites kids to make their voices heard and delivers their creative, funny and vivid messages to the people who have power to make decisions today for their future.

To really listen is a crucial skill that EarthSpeakr urges us all to practise. Recently, I have started extending this practice of listening to non-humans as well, to animals and plants. Through conversations with the Canadian anthropologist and dancer Natasha Myers, I have been trying to introduce some quite basic questions to my artistic practice: What does a plant want? What does it think? And, What does the ice want? What is it saying?

To listen to non-human subjects, to hear them speak, seems to me a task for the years to come. It may make us realise that we must think beyond ourselves to engage in climate action that matches the severity of the present situation. It is a tall order. Nonetheless, I hope and believe that our current worries can turn into positive energy as we feel part of the growing community who are sharing solutions and building an urgent and dynamic climate coalition that crosses national borders, natural and social habitats, and cultural and generational differences.

The architect

The architect

Giulia Foscari, architect, researcher and writer

Close your eyes. Imagine being in the middle of the city you live in, walking under the loudest thunderstorm you have ever heard. Around you, buildings, vehicles, and people busily running to their destinations.

Now envision leaving all behind and embarking on a journey south, sailing across the revolutionary waters of the Southern Ocean towards the Antarctic, and picture yourself standing on the bow of a ship, overlooking a white wall of ice which has accumulated for millions of years. Equivalent to around 70 per cent of the freshwater on our planet, the ice shelf you are staring at, with all its captive evidence of humanity, is not only our largest repository of scientific data crucial to inform future environmental policies but represents also the greatest menace to global coastal settlements threatened by the rise in sea levels.

The sky is blue, the silence absolute, no person in sight. Suddenly, the thundering begins again. Yet the humbling soundscape does not come from above, it emanates from the mass that lies before you. The alarming detonations produced at each rupture of the ice sheet at a pace which is accelerated due to anthropogenic climate change, were my first encounters with the continent and resonated as a call for action.

Buried cross-section of Halley I research station revealed by calving of the Antarctic ice barrier. Credit: A. Alsop, 1995. Courtesy of the British Antarctic Survey Archives Service

Upon my return to my daily life as an architect, I founded UNLESS and launched Antarctic Resolution. Well aware that no single discipline could aspire to synthesise the complexity of the natural and political forces at play in what is unquestionably a global commons, Antarctic Resolution is a multidisciplinary collective platform in which citizens are invited to engage in a coordinated and unanimous effort – independent of nation – to shape the future of Antarctica, and, in turn, of our planet.

The philanthropist

Laura Viegener, CEO of the ALV Foundation

In May 2019 I joined a trip to Greenland organised by Active Philanthropy – an educational adventure on climate change, with world leading climate scientists and inspiring participants. It was all of that and much more. Seeing the decline of the ice with my own eyes and exchanging with locals how their culture has been affected by the changing climate, exposed very clearly how dangerously our current economic system is disrespecting our planetary boundaries. But why was this trip so powerful? We all know about climate change, but this experience sparked a different thinking. To be fully immersed in nature, with no mobile reception and very few people around, allowed me to step back, re-evaluate and realise how much the human species depends on a functioning global ecosystem. We are nature, we cannot live without it, which is why it should be our greatest priority to find ways to incentivise politics, business and communities to regenerate resources we depend upon. A shift from a disjointed worldview towards a whole system thinking, where everything is connected, is necessary.

For me the trip triggered an inner obligation to act. I refocused our foundations’ strategy towards funding regenerative solutions aiming to achieve climate goals. This approach demands to rethink classical philanthropy, fund progressively, be courageous and work collaboratively. In line with this I have understood the potential of the financial markets to drive sustainability. Upon my return from Greenland I participated in the Sustainable Finance program from the University of Zurich and Harvard (CSP) to establish a future fit asset allocation, which is an ongoing process. It includes, amongst other things, setting up a value-based investment policy statement to drive forward a more conscious investment process. Opportunities exist, to go beyond the typical ESG (environmental, social and governance) criteria – shareholder engagement is for example one possibility to increase positive impact. Looking back two years, this Greenland trip made climate change tangible, reconnected me to nature and reminded me to act upon my morals and values.

Comments (0)