1. A heated argument about unrestricted funding

Early one morning some years ago, my wife Sandra and I were marooned in the lounge of our hotel in Kolkata, because a visit to one of our programmes had been delayed by street demonstrations unconnected with the program.

The INGO Manager from London, whose trip we had funded, was with us, and used the available time to lecture us in a forceful manner on the evils of being ‘Donor Led’, saying that her INGO knew how to spend funds more effectively than the typical donor (i.e., us!). It much preferred the ‘gold dust’ of unrestricted funding. She had plenty of courage.

We disagreed since we reasoned that we had had to work for decades of 60-hour weeks to earn the money to give away and felt that donors had every right to a voice in how ‘their money’ was spent.

Ten years later, influenced by visits to over 100 programmes in the Global South, importantly with groups led by The Philanthropy Workshop (TPW), partly through sustained fieldwork on programmes we had funded; and by the results of the recent global Survey by Jigsaw Research which H & S Davidson Trust (HSDT) also funded, I am much more inclined to agree with the INGO Manager.

In this survey, 64 per cent of funders and 78 per cent of frontline implementers agreed that it was desirable to ‘campaign to educate governments and donors on fewer restrictions on funding, and the benefits of more unrestricted funding.’

We have now changed our own practice as a funder, and, within the overall objective of transforming the lives of low-income women and girls in the Global South, most of our funding, both on programmes and on Humanitarian Aid, is close to unrestricted.

2. A purpose for our research

The main purpose is to offer funders, intermediaries, and frontline implementers some thoughts and facts on how to increase impact, learning from our experience and mistakes, and from the recently completed landmark Survey by Jigsaw Research on ‘Reforming International Development’.

Since 2020, we have been working with experts in the field, with Jigsaw Research (winner of Global Agency of the Year in 2019), and with our media partner, Alliance magazine, also a ‘not for profit’ entity, with similar vision and values to our own. We hope you will share this wide-ranging Jigsaw Survey with your colleagues and contacts.

This study is now being further developed by Barry Knight, a co-founder of the #ShiftThePower Movement; Rebecca Hanshaw, until recently the UK Executive Director of Global Fund for Women; with support from Dr Moses Isoba; Chandrika Sahai, and Galina Maksimovic, along with input from approximately 50 global ‘constituents’ occupying different parts of the international development ecosystem, from activist to philanthropist. They have embarked on a process using dialogue to generate data. From this, a co-created version of what a good international system looks like, and critically, how we can obtain it, will emerge.

This approach of listening, learning, and responding resonated with my professional marketing experience. In my working life failure to understand the needs of users, and to recognise them as the primary knowledge holder, would make it impossible to develop superior products or services.

Our joint aim is to present further findings at the #ShiftThePower Conference in Bogota in December 2023, an important stage in what we view as a ten-year programme, designed to develop sustainable solutions.

3. Who we are: The H&S Davidson Trust

HSDT is a smallish ‘not for profit’ charity focused on transforming the lives of women with very low income, and their families, especially girls. It was co-founded in 2004 by my wife Sandra and myself partly from all the funds from the sale of my majority share in Oxford Strategic Marketing, partly from other sources.

HSDT is self-funding – from ownership of properties and company shares. Because we are small, independent, and entrepreneurial, we can afford to take bigger risks than larger funders and are capable of moving faster. Our small team of unpaid Trustees and colleagues has wide experience in marketing, measurement, international management, environmental assessment, and climate change. Each has worked in large and small organisations, in many countries.

We have funded programmes in India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Ghana, and are strong believers in ‘The Wisdom of the Front Line’, both in business and in international development. We are candid about our failures and learn from them.

4. Our impact to date (not enough yet)

Since 2008, HSDT has funded eight programmes in the Global South with two of the UK’s largest INGOs. Total funding was about £3 million, including about £1 million of matched funding. Planned programme length was five years.

Seven pilot programmes were implemented in east India (Kolkata & Odisha), north Bangladesh, the ethnic northern highlands of Vietnam, and the far north of Ghana close to the border with Burkina Faso.

Our Trustees made extensive visits to the front line most years on all these programmes, usually accompanied by someone from Trusts and Foundations at the relevant INGO Office in the UK. We funded the cost of this since we felt it was important for the INGO funders to have first-hand experience of the projects, and it helped us build the relationship.

This process was flexible, but decisions were made outside of the UK with the INGO, local NGOs, community leaders, and us.

We also partnered with a leading INGO in an ambitious programme to improve measurement, which we initiated. This proved a deeply frustrating and hurtful experience for us since our vast experience of working with private sector players renowned for their measurement skills, like Procter & Gamble, was routinely dismissed. In our view it failed, and we closed it after two years. However, the INGO considered it a success.

On all programmes, we did extensive fieldwork, and our process was to ensure that we received and studied all the latest data on the programmes three weeks before departing from UK, so that time was not wasted on presenting these to us on the programme site. We would then agree, ahead of the visit, two or three issues where we all accepted that improvement was needed. Our Itinerary was designed around resolving these issues.

For each project, on the Monday morning after our arrival, the in-country Team would present its views on the solutions to the issues, and we would discuss these and make any necessary amendments to the Itinerary. Everyone was encouraged to participate, and latterly, the presentations were often made by the local community leaders not by INGO people, who were also present. Their efforts exceeded our high expectations. After three and a half days in the field together, we would re-convene on Friday morning, discuss our learning, and make decisions on how best to tackle the chosen areas for improvement.

This process was flexible, but decisions were made outside of the UK with the INGO, local NGOs, community leaders, and us. Most of the time there was consensus because we spent heavily on measurement, much of it done annually, so we all had plenty of facts to work with, as well as the vast local knowledge from those living with the program.

Of the seven pilot tests, all of which covered new ground, six succeeded, and one failed. Of the six, two were scaled by national or local governments, and one by the INGO – it is still running on an expanded basis 16 years later.

Two programmes won international Awards – a UN Equator Award for Poverty Reduction presented in New York to the inspirational leader of the Samudram Fisherwomen’s Cooperative, and a Save the Children Phoenix Award for Innovation presented in Berlin.

Over the past 15 years, HSDT’s activities were initially in teacher training and development of education for street children and child domestic workers. In more recent years we have focused more on programmes to at least double real income and treble empowerment of women workers in rural areas, using scores of women’s self-help groups which proved very effective.

In summary, we estimate, based on numerous annual market research audits from representative household panels, that the Women’s Empowerment programmes more than doubled real income and empowerment levels of 11,000 women and their families (around 50,000 people); and that the teacher training programmes in ethnic areas of Odisha (India) & Vietnam, both scaled up fully or partly by State or National Government, resulted in the appointment of around 3,000 new ethnic teachers in Odisha, while certain elements of the Vietnam programme were adopted in all ethnic areas, accounting for 15 per cent of the national population. Prime credit for these results is due to the highly motivated and knowledgeable workers on the front line, where they lived.

These results are not as good as they sound, since we were favoured by some slices of good luck. For instance, the excellent female head of Primary Schools in our Vietnam pilot area was promoted to a senior role at national level and was instrumental in partly scaling the programme.

One big disappointment was that the most successful programme, in which we were involved, was not scaled, despite achieving spectacular results. Results were measured once or twice each year via a panel of 600 households, representative of the total of 7,000 households involved in the programme. Results were spectacular – the average family income increased by 350 per cent in real terms (adjusted for inflation) between 2012 and 2019. Women’s empowerment, based on six measures, grew from 30 per cent to 95 per cent. Metal sheeting housing increased from 20 per cent to 93 per cent, and mud/bamboo/wood fell from 75 per cent to 2 per cent. The cost per family was £14 per year, totalling £100 for the seven-year period[1].

Total donor investment over the seven-year period was £700,000 (of which HSDT paid half), and annual gain for the 7,000 families was £4.8 million, a RODI (return on donor investment) of 685 per cent. Most investment bankers would like that rate of return!

So, whose fault is it that this programme was not scaled? Mainly my fault. Having later seen the results on scaling from the Jigsaw Survey in 2022, I can see the big mistake made. We should have worked with the INGO and local community on identifying potential scalers at the very beginning of the program, invited their input to the programme design, kept them involved and informed as the programme progressed, discussed their suggestions for improvement, and built their sense of ownership, before approaching them for scaling funds, once they could see the success of the programme.

5. Time for a change in direction

In 2019 we decided to pause, re-consider the issue of scaling, and ask ourselves questions like: What have we done well or badly to date? Are we identifying and learning from our mistakes? Is our impact improving? And, most importantly, how should the International Development Sector in general, and HSDT in particular, change in the next ten years?

One starting point was the opportunity to identify ways to make scaling more effective, in view of our experience outlined above, and because in our travels we had seen numerous examples of ‘rusting pilot tests’, which had been successful but were never scaled.

We commissioned a literature search on the history of scaling, from 1945 onwards from Barry Knight. He produced a definitive report but concluded that ‘Efforts to bring successful results to scale have, for the most part, fallen on stony ground… the problem has structural roots. Public and private funders have always driven change from the top – down, without involving the communities they want to help.’

There was also a lack of consensus on definitions of scaling, and some reservations about its future value and importance. Based on this, we decided to give less priority to scaling in future research on ‘Reforming International Development’. With Jigsaw Research, we therefore aimed to identify topics which people in the sector felt it was important to change, and where there was strong support for specific change from both funder and Implementers on the front line, and both those in the Global North and South.

This process was started by conducting in depth qualitative interviews with 44 well informed people in the sector, from a variety of backgrounds, with an open agenda, designed to identify the topics they felt were most important to change and their ideas for doing so. Based on this mass of data, we developed scores of action hypotheses for change. This was followed through with a quantitative survey of Alliance readers, designed to identify the most important topics for change, and the actions which commanded most support in implementing it.

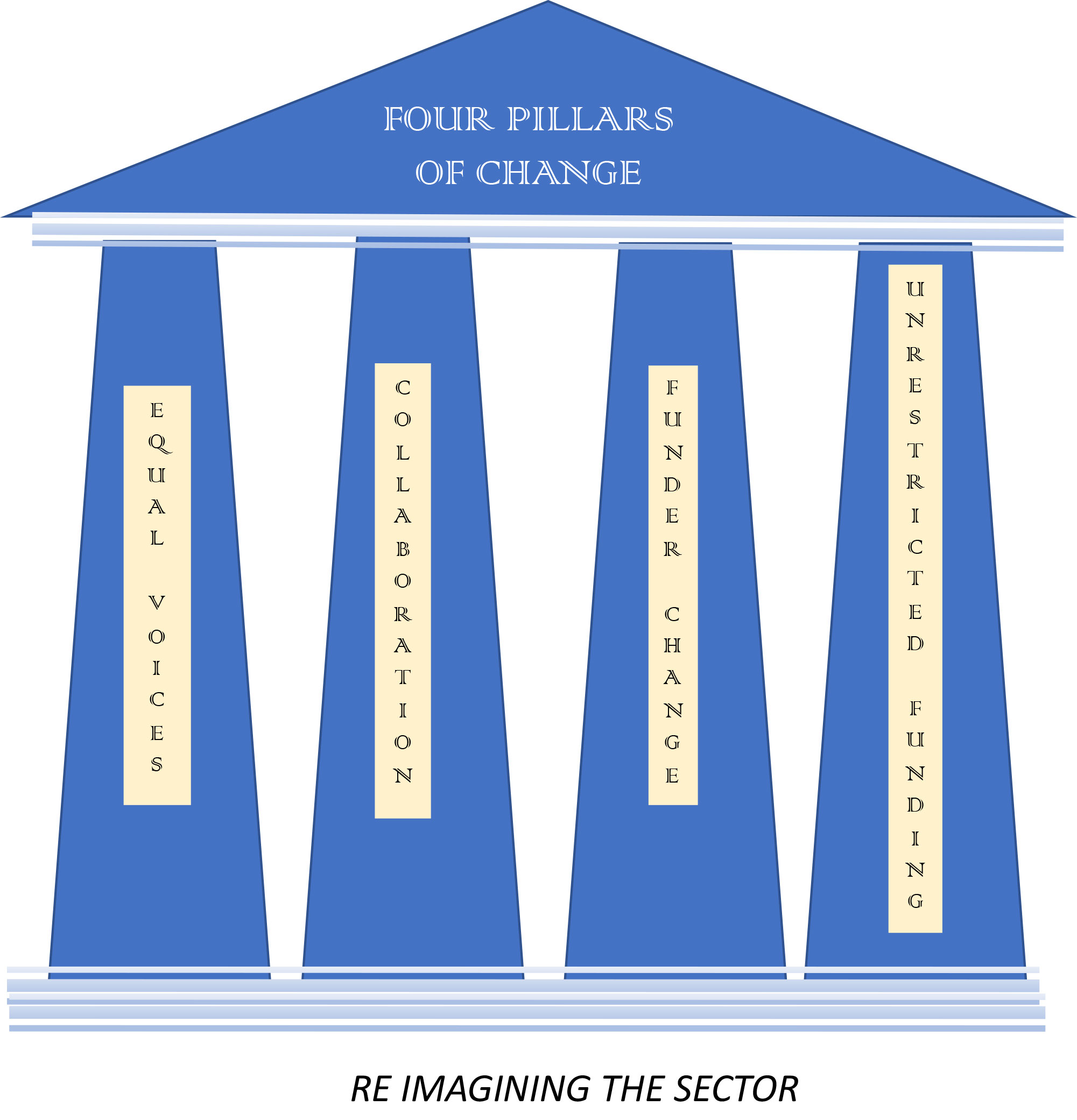

While the sample size at 346 interviews was limited, the magnitude of support for many of the action hypotheses for change was often exceptionally high, in the 70–85 per cent area and added to the significance of the results. There was strong support for a number of changes among both funders and implementers, and people from both Global North & South. Four action areas which met these criteria are summarized below under the heading of ‘The Four Pillars of Change’, and there were others too.

6. Four pillars of change

- Move to equal voices. There appeared to be strong support for Shifting the Power from funders in the Global North to implementers in the Global South: 85 per cent of all interviewees, including 83 per cent of funders, agreed with the statement; ‘Too many funders develop strategies and campaigns in offices in Global North, rather than STARTING on the front line, by understanding needs of local communities in the Global South’

This current practice breaks the number one rule of effective marketing in business: in developing a new or improved product or service, the starting point is to deeply understand the real needs of users on the front line, by listening, listening, listening to them. They are the primary knowledge holders. Unless you do this, you have no chance of developing a superior or differentiated product or service.

- Improve collaboration & knowledge sharing. 79 per cent of interviewees (including 76 per cent of funders) agreed that: ‘Quality and spread of Knowledge Management is poor, with enormous wastage. Knowledge is dispersed among many different players’ (and often never integrated). This is a devastating criticism of the Sector, which contains numerous highly talented people. But many are working in poorly connected silos, like a football team where skilful players rarely pass the ball to each other. There is too much competition, too little cooperation.

In particular, the time-limited project system no longer seems fit for purpose – 78 per cent of interviewees said it was ineffective and unsustainable. Yet it continues as the norm, driving the corroding mindset of ‘Get funds, do project, move on, get more funds’. Can you imagine a business that is continually launching new products which only last for a few years before being withdrawn? They would not last long.

Result of the Project system is constant re-invention of the wheel, and repetition of the same mistakes.

- Funder change. Governments and international organizations are the biggest funders, and they need to change most. But this will not be easy to achieve, since the currency of politicians is votes, the prime future objective of many is staying in power, and international development is not particularly popular in the Global North.

However, the biggest funders could lead change in the application of funds, especially on Equal Voices and Collaboration, and in channelling a much higher proportion of funding to locally driven community organisations. Some are already leading the way on this, with refreshing new approaches.

Some INGOs have already changed, others have plans to do so through such collaborations as RINGO, and ‘Pledge for Change 2030’.

- Unrestricted funding. There seems a need for less restricted funding, more local autonomy. 70 per cent of respondents, including 66 per cent of funders agreed that ‘a campaign to educate governments and target donors on fewer restrictions on funding, & benefits of unrestricted funding ‘ would likely have high impact.

The H & S Davidson Trust made its first unrestricted grant to GFCF – Global Fund for Community Foundations – last year. Based in Johannesburg, South Africa, it invests in local grassroots organizations, while also supporting the #ShiftThePower movement, of which Dr Jenny Hodgson, the founder and CEO of GFCF, is also a co-founder.

Less or unrestricted funding requires mutual trust, and this often needs to be built in small steps over time. It’s like delegation in Management – you delegate more to people in whose integrity and capability you trust. How far could activities like co-designing solutions around community needs first, and increasing support for local NGOs in preparing proposals and designing metrics, build trust? There was strong support for this in our Research Survey from both Global North & South.

7. How HSDT needs to change

Appendix 5 of the ‘Reforming International Development’ Survey by Jigsaw Research, launched in September 2022, covered ‘Changes to HSDT strategy as direct result of Survey’. We have now updated this, and it is included as Appendix 2. One additional recent change, based on further dialogue, has been to make more Humanitarian Support grants for situations like The Horn of Africa, Syria, and Yemen, where the need is dire but there is little media coverage. INGOs tell us that it’s difficult to raise funds for these important causes. Our grants to INGOs are mainly in this area where we think they are particularly experienced, and we have widened our range beyond our long-term relationship with Oxfam to other INGOs which have impressed us, such as Plan International, UNICEF, and Action Aid.

In addition, we are committed to funding the ‘Reforming International Development’ programme for the rest of 2023 (it started in mid 2020, when the Jigsaw Survey was initiated). As it develops, it also needs funding support from funders much bigger than HSDT to reach its full year potential by 2030. We plan to remain a supporter for the long term and hope others will join us in this important plan for change.

Reforming international development is a huge task requiring a long-term commitment. We talk of planting a tree we’ll never sit under. That said we’re motivated to build on consensus from the Jigsaw report and the insights and energy from 11 group conversations. Immediate next steps will focus on the following priorities:

- Creating opportunities for diverse communities and front-line activists to tell us what a reformed international development system needs to look like;

- Mapping examples of change and good practice so we can see what’s happening and what’s working – not only will this be a source of learning and inspiration helping to inform pathways to reform, it will also help build connectivity across sectors reducing silos; and

- Engaging with a broad spectrum of funders and other constituency members to co-create a funding model which balances the needs of all to drive reform

Appendix 1: Women’s Economic and Social Empowerment Pilot Program: Bangladesh. Summary of Results: 2019 vs 2017 vs Baseline (2012).

Appendix 2: ‘Changes to HSDT strategy as a direct result of ‘Reforming International Development’ Survey, by Jigsaw Research (launched Sept 2022), and further discussions/input since.

Hugh Davidson MBE, MA.Chair, H & S Davidson Trust. He has worked full-time as an unpaid volunteer and funder since 2005 and written several books, including The Committed Enterprise – How to Make Vision, Values and Branding Work.

Comments (0)