The news of Pakistan’s ongoing climate catastrophe has crowded out the headlines, but the long-term and actual effects of Pakistan’s floods are yet to come.

Scenes from flooding in Pakistan in 2010 – the last major floods in the country. The nation is still paying off large IMF debts from funds that were loaned a decade ago to help Pakistan manage the economic impact of the flooding. Photo credit: ‘Pakistan floods‘ by Abdul Majeed Goraya for IRIN for UNDP is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

The devastation has caused over 1,350 casualties and over $13 billion in damages. While Pakistan has suffered floods almost every year, scientists say that 75 per cent more rain is falling during the monsoon weeks. For a nation that is already suffering massive IMF debts, The flooding catastrophe will be the biggest propellor of death and impoverishment for years to continue.

Debt makes it almost impossible for developing nations to make the investments needed to achieve sustainable development, build resilience to climate change, and address loss and damage.

The floods are triggered by ‘monster monsoons‘, that shower over Pakistan almost every rainy season. It is estimated by UNICEF that a total of 33 million individuals have been affected and 16 million of them are children. The Sindh province is affected the most, and disease and famine, are disproportionally affecting poor areas. As the long-term effects unravel, cases of water-borne diseases, infections, and skin diseases have already been reported. Villages, schools, farmlands, and hospitals have been overrun, as one-third of the nation remains underwater. The cost of rebuilding these cities will take years or even decades, and the lack of cohesive sustained governments will make this even harder.

Many countries have sent aid to Pakistan over the past few weeks. Canada has pledged $25 million to Pakistan, the US $30 million, and the UK £15 million. The United Nations launched a $160 million aid plan to help with immediate aid for a ‘ life-saving response’ for 5.4 million people in need. The Former Prime Minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan even held multiple live telethons to fundraise for the crisis. After calling out to inbound and overseas Pakistanis, he has raised over 5 billion Pakistani Rupees ($22.7 million).

Many countries have sent aid to Pakistan over the past few weeks. Canada has pledged $25 million to Pakistan, the US $30 million, and the UK £15 million. The United Nations launched a $160 million aid plan to help with immediate aid for a ‘ life-saving response’ for 5.4 million people in need. The Former Prime Minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan even held multiple live telethons to fundraise for the crisis. After calling out to inbound and overseas Pakistanis, he has raised over 5 billion Pakistani Rupees ($22.7 million).

Philanthropic organisations are working to get on-the-ground assistance. Disaster philanthropy is holding recovery fundraisers to provide shelter, food, and health in Pakistan. According to Candid reports many corporate grants have been given out as well, Bestway Group donated $1 million to help people affected by the floods, Meta employees raised 125 million rupees ($1.6 million), and H&M Foundation provided $250,000 in funding to Red Cross/Red Crescent to support the people affected.

Insufficient aid

While all this aid is beneficial for immediate financial assistance, it is not enough to create change on the systemic level. This form of philanthropy is merely a drop in the hat for a nation like Pakistan which experiences this and various other climate catastrophes consistently at the hands of the Global North. Candid noted in their 2018 Annual Review of Global Foundation Grantmaking, that Aid sent by nations in the global north was often restricted and posed a ‘trust gap.’

‘The major differences in core support suggest a deeper cultural issue in the field of philanthropy’, Candid said, explaining that local funders rarely receive funding, while the established organizations provide aid that is restricted or doesn’t even reach the target areas. Additionally, many of the corporations donating also contribute to some of the world’s highest climate emissions. Understanding that the floods are not a stand-alone event is key in recognizing that it is a direct outcome of years of resource extraction, climate injustice, and colonial and military regime. All of which are affiliated with western imperialism.

‘The major differences in core support suggest a deeper cultural issue in the field of philanthropy’, Candid said, explaining that local funders rarely receive funding, while the established organizations provide aid that is restricted or doesn’t even reach the target areas. Additionally, many of the corporations donating also contribute to some of the world’s highest climate emissions. Understanding that the floods are not a stand-alone event is key in recognizing that it is a direct outcome of years of resource extraction, climate injustice, and colonial and military regime. All of which are affiliated with western imperialism.

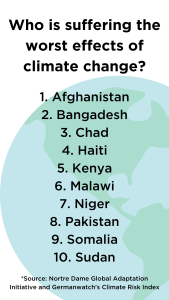

Further, according to the Global Climate Risk Index, Pakistan is the eighth most vulnerable country to the climate crisis but contributes less than one per cent of global warming – and less than 0.50 per cent of carbon emissions. Sherry Rehman, Pakistan’s climate change minister, commented on this injustice in The Guardian saying: ‘There are countries that have got to become rich on the back of fossil fuels and let’s be honest about this. Now the time has to come to make a change and we all have a role to play but they have a greater role in this climate catastrophe.’

Scientific data discusses this overshoot in emissions by the Global North. In a research paper done by Jason Hickel, 2015, he finds that ‘The G8 nations (the USA, EU-28, Russia, Japan, and Canada) were together responsible for 85 per cent [of emissions]). Countries classified by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change as Annex I nations (ie, most industrialized countries) were responsible for 90 per cent of excess emissions. The Global North was responsible for 92 per cent.’

Although the paper is dated, it is projected that these numbers have gone up – not down. The author recently tweeted in the about Pakistan’s flooding that: ‘Right now none of [the global north nations] are on track with what is required to stay under 1.5°C with any consideration of justice or equity principles.’

A case for climate reparations

Margaretha Wewerinke, an Assistant Professor of Public International Law at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who said that international cooperation is a must to ensure climate justice.

‘Addressing the climate crisis, including loss and damage, requires international cooperation based on the international rule of law. International law requires that developed countries provide climate finance for mitigation and adaptation in developing countries—not as a matter of aid, but as a matter of obligation,’ Wewerinke said, reinforcing the idea that Pakistan and other nations in the Global South should be paid reparations for crises that are not their fault.

Wewerinke said that this situation is similar to other nations in the Global South.

‘The current floods show the severity of climate impacts already suffered in the Global South, and we know it is only going to get worse,’ she said. ‘Philanthropy is an inadequate way of addressing these impacts. A decolonized approach to philanthropy involves a greater respect for the international rule of law and International cooperation towards the realization of human rights everywhere.’

It’s not a question of aid, it’s a question of justice. The amount of money promised in terms of flood relief is still not even close to what is needed to cover the damage and, it doesn’t account for the massive profits that were made off of this capitalist economy that has led to the situation in the first place.

Today Pakistan holds $130 billion in IMF debts, all the while inflation and the cost of living rise, and foreign regimes take over effective governments. One study found that ‘Poor nations spend five times more on debt than climate crises.’

In terms of global legal responsibility for floods, Wewerinke said ‘Debt makes it almost impossible for developing nations to make the investments needed to achieve sustainable development, build resilience to climate change, and address loss and damage.’

‘In addition to debt cancellation, there is a need for scaled-up climate finance in accordance with international law and honouring political commitments,’ Wewerinke said, arguing for a legal stand on climate finance.

In 2010 during the floods disruptions, the IMF issued $450 million in loans for the crises that needed to be paid back. Oxfam International, a global poverty alleviation organization, spoke out against this arguing that it was counter-productive to economic empowerment in Pakistan.

‘After a week of talks with the IMF, Pakistan has not been given what it needs to recover from a disaster of this magnitude. This is a disappointingly inadequate response. Pakistan cannot be expected to service debt as it struggles to cope.’ said Elizabeth Stuart, an Oxfam spokesperson.

The same rationale can be applied here, as climate justice activists and professionals call for wealthy nations to pay climate reparations.

‘I don’t think it’s it shouldn’t be framed as philanthropy makes it sound like those who are giving the money are doing it out of the goodness of their hearts, which creates the kind of power relationship between those who are providing aid and those receiving,’ said Dr Nida Kirmani, an associate professor of sociology at LUMS University in Pakistan, reflecting on the power relationship that emerges from the term philanthropy.

Aid, like situation described above, is often handed out in situations where colonized nations beg for money, and that often comes with strings attached, leaving the colonized vulnerable to the colonizer. It is the very reason why philanthropy aid is ineffective in Pakistan’s circumstances and that of many nations in the Global South.

The Koh-i-noor diamond was taken from the Indian Subcontinent in the 13th century. It is now in the British Royal collection of Crown Jewels. Photo credit: ‘Koh-i-noor diamond‘ by aiva. is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

Dr Kirmani also said that, compared to debt in resources the global north owes to Pakistan, what is being offered now seems to be mere pennies. ‘It’s not a question of aid, it’s a question of justice,’ she said. ‘The amount of money promised in terms of flood relief is still not even close to what is needed to cover the damage and, it doesn’t account for the massive profits that were made off of this capitalist economy that has led to the situation in the first place.’

This event is largely the fault of the American and British regimes in Pakistan and the western world’s lack of responsibility for the crises they created. Stolen money and resources and the climate crises are intersectional. Britain stole approximately $45 trillion from India pre-independence and partition. Before Britain’s economic imperialism, the Indian subcontinent was a quarter of the world’s economy and less than three per cent after independence. Even today countries like Pakistan are used as cheap labour for western corporations, and as sites for mineral resource extraction, this too is a form of economic imperialism.

After the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, many colonial nations publicly called for compensation, the Koh-i-Noor diamond, which is a royal jewel, was taken from the Indian Subcontinent in the 13th century. For NBC, Danielle Kinsey, a historian at Carleton University adds how the extraction of resources is economic injustice for these nations.

‘It has a history of being part of war booty or trophies taken as the result of the war in South Asia. So in a lot of ways, it is a symbol of plunder and represents the long history of plunder imperialism,’ Kinsey said.

‘Beyond climate reparations, what Pakistan really needs are colonial reparations,’ said Shozab Raza, editor of Jamhoor magazine.

Philanthropy is seen as charity – but reparations are a responsibility, a duty for nations that deprived, not just Pakistan, but many nations across the Global South. Regardless of urgent need, for us to fully decolonize philanthropy and see economic justice, reparations must be paid.

Aina Marzia is a Journalist and Reporter Based in El Paso, Texas. She covers intersectional political and cultural beats, her work has been seen in Teen Vogue, Allure, Yes! Magazine, The Austin Chronicle, Prism Reports, and more. Reach her on Twitter at @ainamarzia_ or LinkedIn.

Alliance magazine’s climate change coverage is supported by Fondation de France.

New issue: Decolonising philanthropy

The word ‘decolonisation’ was coined to describe the withdrawal of colonial powers from territories they had occupied. What forms have decolonisation practices taken among foundations? Should philanthropy be making reparations? And what significance does decolonisation have for philanthropic institutions when they are geographically distant from the former colonies? These are among the questions to be explored in the latest issue of Alliance. Guest edited by Shonali Banerjee, Centre for Strategic Philanthropy, Cambridge University and Urvi Shriram, Indian School of Development Management.

The word ‘decolonisation’ was coined to describe the withdrawal of colonial powers from territories they had occupied. What forms have decolonisation practices taken among foundations? Should philanthropy be making reparations? And what significance does decolonisation have for philanthropic institutions when they are geographically distant from the former colonies? These are among the questions to be explored in the latest issue of Alliance. Guest edited by Shonali Banerjee, Centre for Strategic Philanthropy, Cambridge University and Urvi Shriram, Indian School of Development Management.

Subscribe today to read it!

Comments (0)