Social movements have rarely featured in funders’ theories of change or strategies. This is slowly changing and international interest in movements is rising

Friday’s for Future, NiUnaMenos, Lucha, #BlackLivesMatter, the uprisings in Chile and HongKong, #MeToo, Le Balai Citoyen, Abahlali BaseMjondolo… the civic space is radically changing. Where in the last few decades ‘formal’ third sector organisations have dominated civil society, social movements and other civic actors are now playing a central role. Their relevance is highlighted by the swift responses of alternatively organised mutual aid groups to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite their prominence, social movements have rarely featured in funders’ theories of change or strategies. Data from Candid in the US suggests that funding for social movements accounts for less than 1 per cent of funding; in the Global South, institutional funding for movements is minuscule. This is slowly changing. In Europe, the emergence of Extinction Rebellion and Fridays for Future have put movements on the funding map, sparking curiosity and imagination. In Africa, international interest in movements is gradually rising.

As guest editors of this issue of Alliance , we have tried to bring together voices from around the world to raise the profile of progressive movements for equality and justice in the hope that it inspires the funding community to (i) think how to respond to a civic space that is broader and deeper than it generally supports; (ii) deepen their understanding of movements and explore appropriate ways to engage; and (iii) get excited about the potential of the work of movements. The voices featured in this issue were selected to provide an overview of social movement philanthropy drawing on our respective vantage points across Africa, Latin America and Europe.

Understanding movements

Social movements, while not homogeneous, are a way for people to give voice to and address grievances and systemic injustices – from the local to the transnational. Through collective action and the enactment of alternative values, they seek to alter existing power structures and prefigure their societal vision. Movements are thus not only sites of resistance but also important actors in producing alternative forms of social relations, ways of working and organising, and political authority.

Many movements have different but related concerns and engaging these appropriately will require a holistic funding approach.

Movements employ multiple approaches. The Intersex Movement for instance, works through smart advocacy and coalition building, while a national-level mass movement like LUCHA uses large scale mobilisation combined with advocacy. The configurations are many. While the majority of progressive movements are non-violent, there are those where violence is part of the movement strategy or is provoked by repression. There are also movements who gradually become political, demanding regime change to end social injustice. How funders engage, if at all, with these are often much debated.

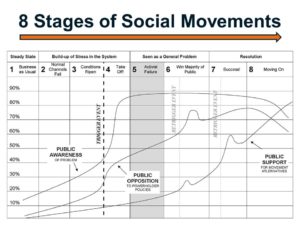

Movements are like ecosystems: a web of interconnected campaigns, people, groups and networks, whose frames, tactics and demands evolve dynamically; where distributed leadership and downward accountability often dominate as principles and uncertainty and risk are inherent elements in operations. They seldom institutionalise, their nature is constantly negotiated, and their form varies according to constituency, tactics and context. They thus have structures and processes that are unfamiliar to foundations and so remain marginal in funding strategies.

Why should philanthropy engage with social movements?

In spite of these difficulties, we argue it is vital to move beyond seeing institutional form as the criterion for legitimacy and to think much more comprehensively about what civic action looks like in all forms, how we can engage these without harming, and enable organic civic spaces to lead. As Theo Sowa notes, it is not philanthropy’s role to seed movements, but to support those that emerge. As important, movements serve as expressions of local agency. If our goal is systemic change so that people can claim agency, then we need to see support for movements (and other alternative organising) not just as means to an end, but as important civic spaces in their own right.

Do movements even want our funding?

It is important to recognise that self-financing and other types of resourcing by movement participants and their individual supporters form the bedrock of the sustainability of social movements. In Europe, many southern European progressive movements have little or no experience with foundations, and activists often express negative attitudes towards funders . This is unsurprising because the foundation landscape is dominated by banks and private companies whose conservativism precludes engagement. Alternatively, in countries like Germany or the UK, with a small but established infrastructure of social movement funders, resources are flowing into non-financial support for social movements in the form of trainings, network formation or campaign coaching. Here, crowdfunding also allows movements to remain independent from funders even if accepting institutional support.

In Latin America, newer independent local funds play a fundamental role in resourcing movement activity. Although corporate philanthropy plays an important role in Latin American philanthropy mainly in Mexico and Brazil and to a lesser extent in Argentina, Colombia, Chile and Peru, social movements certainly do not occupy a prominent place in their agendas.

Engagement must be rooted in what movements deem relevant, not in how funders ordinarily fund the third sector.

In Africa, local foundation contributions for movements are minimal and those from international funders are slowly emerging. With some exceptions, African movements do not want external funding for core activities and actions – preferring to find it within the movement and through support from communities and the diaspora. While they are open, in principle, to institutional funding to magnify impact, deal with emergencies, enable solidarity and broaden advocacy, their proviso is that funding must not impose external priorities. The experiences of several African movements have shown that many funders have not been able to refrain from this agenda setting.

In India, anecdotes reflect that many movements neither seek nor accept external funding, seeing it as a threat to their work and values. Any engagement with movements thus needs to be grounded in what they themselves think appropriate.

Money and power

Given the potentially corrupting effects of external funding and the potential displacement of internal resourcing mechanisms, does funding destroy more than it helps? Several points require consideration. First, our current extractive neoliberal economic system, rooted in patriarchy and secured by top-down militaristic governance, is the result of a concerted – and well-funded – effort of the political right. It seems naive to assume that we can turn things around just with the funding that comes from communities suffering oppression and exploitation themselves.

Second, money can be harmful for movements, but smart funding can help build space for reflection, peer support and strategic adjustment to help think through some of the challenges presented by inequitable access to information and distribution of power.

Third, as Gambian activist Muhammed Lamin Saidykhan notes in his article, money often brings with it demands that movements conform to funders’ requirements – actively challenging and limiting their action, so it is important that funders think about ways to avoid this. Here, local funds such as the Prospera Network of women’s funds and the Brazilian Philanthropy Network for Social Justice, are playing an important role involving marginalised populations in their funding of movements. Other funders like Grassroots International, Bewegungsstiftung, Thousand Currents, Solidaire, The Guerrilla Foundation, African Women’s Development Fund, and Urgent Action Fund-Africa, are showing that it is possible to foster respectful, appropriate and effective relationships between funders and movements. Collaborative, movement-led and participatory funds like that being set up by a collaborative involving Afrikki and others, demonstrate potential options for advancing movement-led decision making on funding.

Funding movements means understanding and trusting a way of working that might be far from your comfort zone. Trust is critical. When established, funders can act as amplifiers of movements rather than competitors.

Politics vs party politics

Funders are often hesitant to engage with movements because (particularly in the Global North) their charitable status restricts them from influencing party politics. However, funders are often over-cautious about this: where movement demands are not politically partisan and/or are aimed at transforming democratic practice, foundations can and should get involved. For example, foundations could support organising efforts to stimulate community action on issues and increase the capacity of people to make use of the political system. If, ultimately, new political parties emerge from an organised civil society and take over municipal governments, foundations might help publicise such successes, support networks of municipal actors, or help the creation of a new politics from below. Foundations need to stand up for the values they want to see in society; we strongly believe that the crises of our time demand all of us to be political, as individuals and within our institutional capacity.

Intersectionality and cross-movement organising

Despite evidence reflecting the intersectionality of the challenges faced, most funders continue to silo their support. Many movements have different but related concerns and engaging these appropriately will require a holistic funding approach. Philanthropy can create fertile ground by funding community organising, supporting the spread of a movement by strategically convening people or offering platforms for movement advocacy that link to transnational/global fora. Philanthropy can also fund broad-based organising, cross-movement organising, movement infrastructure/support spaces and shared civic platforms – but too little of this is currently happening. Doing so requires that funders make a fundamental shift from questioning the role of movements to thinking about how they can best support a civic space where movements are an intrinsic role-player.

Outcomes and impact

Funders frequently measure outcomes in narrow, project-oriented ways. Movements, operating with longer-term horizons, in fluid contexts, require them to adopt an altered perspective on what they value and how they measure it. So, could we look at organising as a way to build relationships and solidarity, rather than look for a successful campaign? The Occupy movement, for example, was ‘unsuccessful’ in that demands weren’t fulfilled but provided an important inflexion point for many activists who continue to do social justice work.

From strange bedfellows to partners: how should philanthropy engage?

Recognise that movements know best what they need: the biggest shift funders must make is acknowledging that they do not know best. Engagement must be rooted in what movements deem relevant, not in how funders ordinarily fund the third sector, or even in how they fund movements in the North.

Understand and become part of the movement ecology: attend meetings, listen to participants, discuss the risk you’re willing to take institutionally and let that inform your strategy. Learn as you go along until you’re knowledgeable enough to identify and work with promising grassroots groups and activists, without directing them. Foundations need to recognise the different actors in movements (reformers, rebels/activists, citizens and change agents according to Bill Moyer’s Movement Action[1] Not every foundation needs to support the ‘rebels’ but, building on their work, can support the change agents and reformers to develop long-term solutions and policies for issues that were first taken up by activists.

We are in an unprecedented time where going back to normal is not the goal because, in fact, normal is the problem.

Understand alternative methods of organising: activists are often involved in multiple groups and collectives, working on intersecting issues, and funders need to look at cross-movement organising and intersectional ways of support, without demanding institutionalisation as a pre-requisite – which often harms movements in significant ways. Funding movements means understanding and trusting a way of working that might be far from your comfort zone. Trust is critical. When established, funders can act as amplifiers of movements rather than competitors.

Don’t pretend you’re neutral! Supporting movements requires that we take sides and question our own values and practice. Movements often question the origins and role of foundations in maintaining the status quo, and funders need to engage this. Participatory processes in foundations and participatory grantmaking are potential ways to build trust and increase accountability to those you serve. Foundations need to further align themselves with the movements they support and contribute to changing philanthropy by advocating for meaningful engagement with social movements by other funders.

All of this demands that funders dig deeply and honestly into their motivations for wanting to work with movements, and acknowledge that there exists fundamentally different theoretical and practical approaches to how a just society can be achieved. We are in an unprecedented time where going back to normal is not the goal because, in fact, normal is the problem. As funders, we must be ready to make the changes we demand of others.

Halima Mahomed is an independent philanthropy consultant and researcher.

Email: halimamahomed@gmail.com

Twitter : @HalimaMahomed

Graciela Hopstein is executive coordinator, Brazilian Philanthropy Network for Social Justice.

Email: gracielahopstein@gmail.com

Romy Krämer is managing director, Guerrilla Foundation.

Email: romy@guerrillafoundation.org

Twitter: @romykraemer

Comments (1)

A great read, thank you and greetings from Harare! Please keep up the good work to increase support for grassroots movements.....since global leaders have failed us (e.g. COP....what has it really achieved? just a lot of very expensive talk and flights and non-binding commitments....the only real action is being taken on the ground by communities....even our CHILDREN have done better than our leaders.....Greta/school strikes etc)