The security and political crisis in Afghanistan has touched many around the world who are ready to help, host and welcome Afghan refugees as the Taliban carefully calibrate and repackage their religious brand, using a very ‘Western’ social media strategy.

The global response for Afghans and, in particular, in support of Afghan women and girls is laudable as it speaks to the essence of philanthropy, the love of humankind. But to be effective and far-reaching these efforts need to be framed and contextualised to respect the human dignity of those in whose name human compassion is unleashed.

Framing Philanthropy

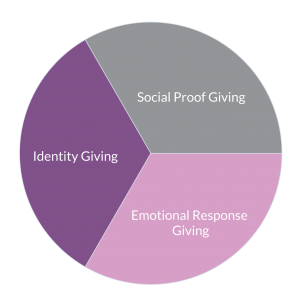

As Simon Sinek brilliantly advocates, let’s begin with the Why. The first step in framing any charitable effort is to understand the motivations for giving. Typically, the majority of giving consists of ‘identity-giving’ (say religion or alma mater), followed by ‘social proof-giving’, which Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker describes as ‘appearing beneficent and generous’ or ‘earning friends and cooperation partners’. In some cases, these may overlap with ‘emotional response-giving’, such as donations made in response to natural catastrophes, humanitarian crises, epidemics, or disturbing storytelling, as in the case of Afghanistan currently.

A Typical Philanthropic Portfolio

A Typical Philanthropic Portfolio

Questioning why one is giving is fundamental not only for self-honesty – a rare commodity in a world of blitzkrieg self-marketing – but to maximise one’s impact.

Here are some suggestions:

- Consider thoughtful, rational giving for a sustained period of time. While emergency funding is needed, consider what happens next. Is short-term, punctual funding creating other unmet needs for those evacuated and embarking on a long resettlement journey? What can be learnt from so many global cases of ‘compassion fatigue’? Is your giving mindful of the 40 million people quite literally ‘left behind’?

- Let your motivation intersect with the need of the end-user. Because philanthropy is fundamentally top-down, a power relationship, it needs to be balanced by an understanding of the need of the recipient, the end-user. For instance, would you consider giving your own child lots of pens as a proxy for a good education? Or building a school with no teachers? Or wearing donated clothes that may be unsuitable? And yet many well-intentioned efforts treat recipients like this. Understanding the need of end-users through real empathy – a key principle of design thinking, consultation and feedback is not only recommended but is also respectful of the dignity of fellow human beings.

- Move the focus from the act of giving, and amount, to the result. What are you aiming to achieve? What is the desired result of your donation and how will you know your impact was positive? Success in philanthropy must go beyond giving and self-promotion, towards aiming, listening and impacting lives through validation by the end-users.

Following these three simple rules may help to fix a philanthropic system that is too often short-term oriented, top-down and disconnected from results.

Contextualising Philanthropy

In a world of information overflow, ubiquitous ‘breaking news’ and remarkable access to knowledge and research, it should be easy to demonstrate ‘the love of humankind’ through a more thorough understanding of context. While the previous section is cautioning around the tendency of philanthropists to decide for the end-users, here the cautioning is around how philanthropists talk about the end-users. Here are some suggestions:

- Avoid speaking in generic terms, also about women. Would you like an aid project to be labelled as for ‘American women’ or ‘British girls’. There is no such thing as a homogeneous group called ‘Afghan women’. They are, as in every other country on earth, different and similar based on the urban-rural divide – some 75 per cent of Afghans live in rural areas, as well as on their ethnicity, class, tribe etc. For instance, in capturing Herat, the Taliban were met by women with AK-47s ready to defend their freedom, families and the cultural heritage of their city. However, the bulk of women living in rural areas may be far less concerned by the change of regime. Labelling matters, particularly if it is further disempowering.

- Read more, read history (or ‘her story’). 1979 is a seminal year in history, particularly to understand the rise and success of particular religious discourses. In Afghanistan, however, the role of the United States and other allies, including Gulf countries, in supporting these against the backdrop of the Soviet invasion, is well-documented. 99 per cent of Afghans had access to radios and batteries, even under the Taliban, which ruled the country from 1996 to 2001. This is generally a highly informed, engaged as well as hospitable, dignified, and poetic people. The irony of history will not escape them – both for those who manage to migrate to the West and for those left behind, yet again. The current plight of Afghans may be new to some, or ‘trending’ thanks to an awakened media, but it is sadly not new, entirely man-made and deplorably predictable.

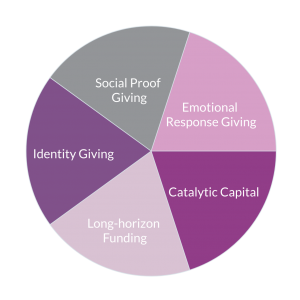

- Be solutions-oriented. In the last two decades some phenomenal Afghan entrepreneurs, including female entrepreneurs, created viable businesses both in Afghanistan and beyond. Many of these ventures struggled to find seed or growth capital, both externally and internally. Now may be the right time to use philanthropic capital to invest and support such businesses both in-country and globally, particularly if they help to develop products or services that are relevant for Afghanistan and other similar contexts. Think of basic services around education, health care or supply chain. In a country with a 40 per cent dependence on rapidly decreasing foreign aid, some 70 per cent mobile penetration and over 20 per cent of Internet connectivity, the potential to help some 40 million Afghans and hundreds of millions more in neighbouring countries, is massive. This kind of philanthropic catalytic capital, or solutions capital, may soon be the only type of capital available to fill the gap by foreign aid agencies and pave the way for daring private investors. Long-term horizon funding, in the form of educational endowments and research, will also be needed to make a dent in seemingly intractable challenges in the region. With the right framing and understanding of context, a suggested philanthropic allocation could look like this:

A New Model Philanthropic Portfolio Allocation

A New Model Philanthropic Portfolio Allocation

What Afghanistan teaches us, yet again, is that if we are to honour our shared humanity, our response must involve heart, and mind, to imagine and actually build a better future for all.

Farahnaz Karim is the founder of Insaan Group, an impact investment entity that allocates philanthropic capital to tackle poverty. She worked in Afghanistan during both what was known as the Taliban era, and the post-Taliban era.

Comments (0)