Civil society is under fire—sometimes literally—in many countries and in all regions of the world. Governments are clamping down on fundamental civic freedoms. This year’s Global Risks Report highlights the threat to civic space, noting ‘a new era of restricted freedoms and increased governmental control could undermine social, political and economic stability and increase the risk of geopolitical and social conflict.’

Civil space is defined by three fundamental rights: the freedom of association, freedom of assembly and freedom of expression. The attacks closing down civic space come from a host of angles, including from political leaders who want to shut down dissent, government agencies regulating how people communicate or associate, security services trying to protect national security, and organized crime and extremists trying to silence their enemies. These crackdowns pose a threat to open and free societies and erode the underlying framework of a stable economic environment which businesses need for investment and operation.

People run as Turkish riot police use water cannons to disperse protesters on November 5, 2016 in Istanbul. Photo credit: Yasin Akgul of AFP.

Historically, driving progress and innovation across the political, social and economic spheres has been a stalwart trait for civil society actors. They have advanced human rights, the rule of law and sustainable development; shutting off civil society today puts efforts such as migration crisis solutions, implementing the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and pushing for transparent government at risk.

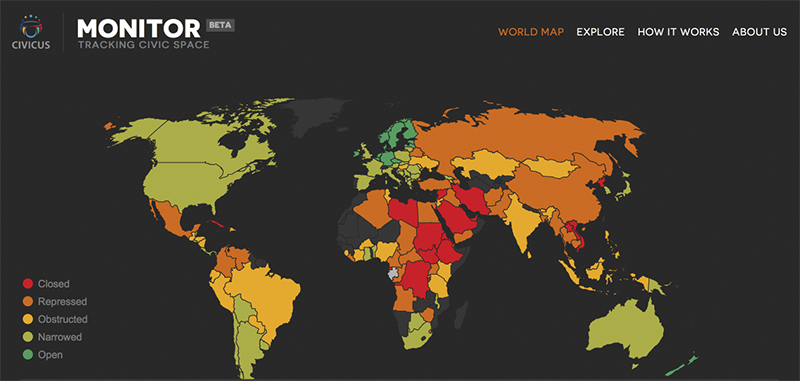

The recently launched CIVICUS Monitor shows that more than 3.2 billion people live in countries in which ‘civic space’ is either closed or repressed. It also shows that conditions in few countries—16 out of 134 countries with verified data – are genuinely open. This means that scope for citizen action is constrained and getting worse in much of the world, including some countries – such as the United States – where one might least expect it. The spillover effect to other countries cannot be understated.

Taken globally, these developments threaten the very social solidarity on which the legitimacy of our economic and political systems rests.

Trust in established political institutions such as parliaments and political parties is low and falling, leaving a vacuum that regressive and undemocratic forces have filled. The challenge for progressive businesses and civil society is to come together to defend fundamental freedoms and find new, constructive ways of channelling the thirst for citizen participation. This will require new levels of cooperation between civic leaders and business, but it will also require us to tackle big issues that drive feelings of insecurity.

For too long businesses and governments have failed to invest in, and at times undermined, civil society—the social glue that brings communities together, that allows for grievances to be aired and power to be challenged. A healthy and vibrant civil society can also help prevent the kind of runaway inequality that undermines stable economic and political environments. The Brexit vote, the election of Presidents Donald Trump in the U.S. and Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and the rise of populist political movements across Europe and elsewhere all point to society in turmoil.

Sadly, it has not been difficult for political leaders to whip up discontent with the current global economic order—leading, in many cases, to a rejection of the concept of global—or regional—cooperation. This is hardly surprising since, according to the Global Risks Report, the most important global trend of the next 10 years is rising inequality.

Businesses and governments have failed to convince citizens that globalization is in their interests as well. To many citizens, it seems like business and governments have colluded to amass all of the benefits of the global economy without considering the importance of investing in the communities their profits come from.

At the heart of the challenge lies a deliberate misrepresentation by some political leaders and media pundits of the nature and value of civil society: those formations that engage “good causes” are seen as good and those that seek to channel political grievances or empower citizens are seen as problematic.

It is easy to see the value of civil society in delivering development projects and social services that states are unable or unwilling to provide. But the true value of civil society lies in its diversity and freedom, including undertaking functions such as advocacy, sensitization about rights, mobilization, research, documentation and pursuing accountability. These functions of civil society may make life uncomfortable for political and business leaders on occasion, but we need to work hard to protect a vocal and vibrant civil society.

The challenge is also felt at the international level. Restrictions on international funding for civil society organizations have prevented them from working across borders. These restrictions have also made it more difficult for civil society to work in some of the world’s poorest countries—including on issues related to climate change despite the global nature of the threat. Meanwhile, civil society organizations continue to have only limited involvement in multilateral organizations.

As the 2017 Global Risks Report shows, there is a growing rejection of the global cooperation that businesses have come to rely upon. Supporting civil society to work across borders is one way that businesses and governments can work to ensure that local and global communities maintain the stability needed to support ongoing and inclusive economic growth.

Danny Sriskandarajah is secretary general of CIVICUS. Email danny.sriskandarajah@civicus.org

This article originally appeared on the BRINK website on 14 February 2017. The original article can be found here.

Comments (0)