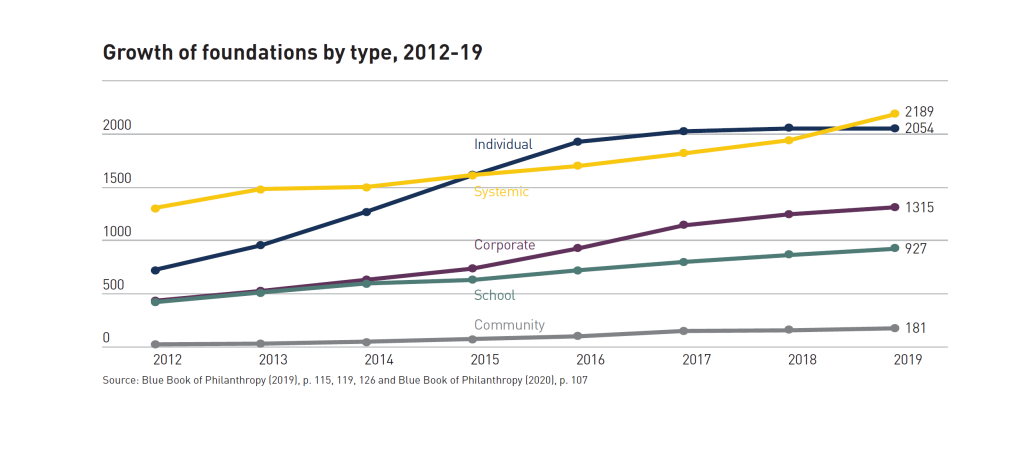

China is rapidly becoming one of the most philanthropic nations in the world. While it is impossible to know with certainty how much philanthropic capital is flowing, we do know that it is, and in massive amounts. One indicator of this is the explosive growth of foundations. According to China’s Blue Book on Philanthropy, the number of foundations soared from around 3,000 in 2012 to almost 8,000 by the end of 2019.[1]

Philanthropy in China is unique and has distinct Chinese characteristics. This is particularly due to the structure of China’s social sector. ‘Foundations’, known as jijinhui (基金会) in the Chinese context, are a good case in point. There are five different types of foundations in China. Some of them are grantmaking and act much in the same way as foundations around the world. Others are operating foundations that are more akin to NGOs. A large segment are systemic foundations or ‘GONGOs’ (government-organized non-governmental organizations), a seemingly contradictory but widespread organization structure in China.

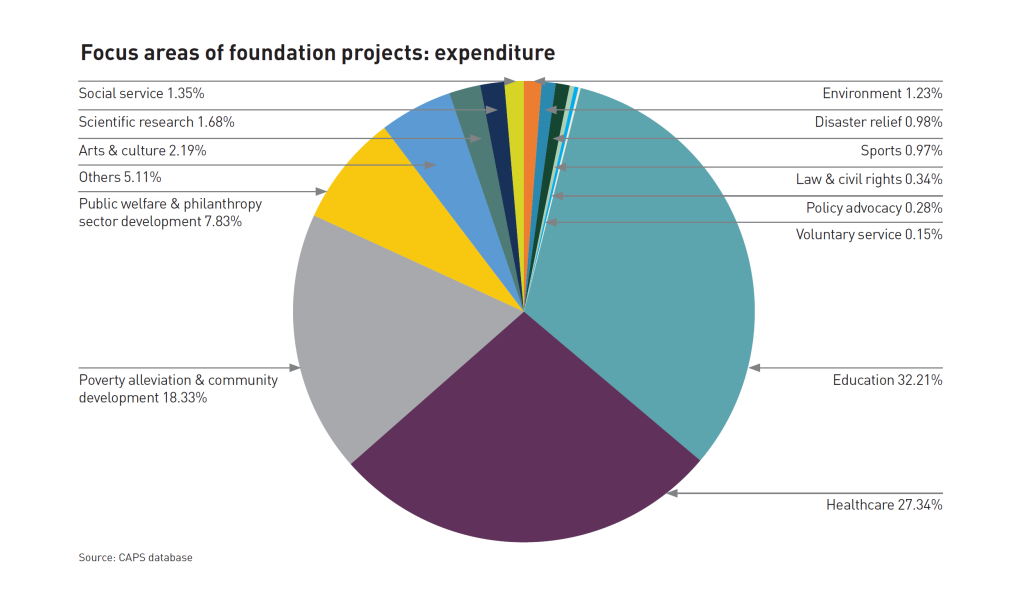

CAPS’ China Issue Guide study examines at a project level how philanthropic capital is deployed in China. Our findings reveal philanthropy in China is a highly coordinated, cross-sectoral effort that cuts across the public, private and social sectors. The study is divided into four reports, each focusing on a key issue for philanthropic support: health, environment, education and poverty alleviation.

Health philanthropy

By our most conservative estimate: health projects in China account for less than 10 per cent of all charitable projects. At the same time, 27 per cent of total philanthropic spending, or ¥27.04 billion (approximately US$4.18 billion), went to healthcare projects between 2017-18, second only to education.[2]

But where does this funding go and how does it reflect Chinese characteristics of philanthropy?

When we talk about philanthropy with Chinese characteristics, we first have to acknowledge the relationship with government policy and government agencies. Health philanthropy, like other forms of private social investment in China, tends to be aligned with government priorities and initiatives. As exemplified by the existence of GONGOs, sometimes philanthropic activities are organizationally linked.

For example, we found that 43 per cent of health philanthropy went to ‘major disease assistance’ (大病救助), a cornerstone of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s flagship campaign on poverty alleviation (脱贫攻坚), carried out from 2015-20. Specific activities under this label include cash payments for basic health insurance costs and hospital bills that are only partially covered by insurance, drug donation or subsidies, and donations supporting livelihoods of patients and their families. These measures aid the goal of poverty alleviation. The program succeeded in channelling a great deal of philanthropic capital to augment government programs and provided a blueprint for future efforts, including the current push for ‘Common Prosperity’ (共同富裕).

While drug donations have been a significant portion of all health-related philanthropy—estimated at 35 per cent of the total pool—since well before the poverty alleviation campaign, pharmaceutical companies can be seen to be diversifying their patient assistance projects, to include screening and patient education and care. This diversification is occurring in tandem with the government’s increased focus on health promotion and management.

Alignment with government is critical to operating in China.

Another characteristic of philanthropy in China is the tendency for individuals and businesses to utilize their expertise and resources to craft solutions. These efforts can supplement government programs but can also be used to craft and pilot social innovations with the hope that government picks up the solution and establishes policy around it.

Meinian OneHealth, which runs for-profit health centres across the country, provides a good example of private resources supplementing existing government programs. The company provides free check-ups and health education for vulnerable communities in clear alignment with Healthy China 2030, a national strategic plan that calls for the transition from curative care to one of health promotion and management.

Founder of Ribo Group, Qu Jiangting, demonstrates philanthropy supporting social innovation. After a boating accident left her with depression, she found mental healthcare difficult to access partially due to the stigma surrounding it. After her recovery was aided by positive psychology and coaching, Qu was motivated to create the Flourish Magic School program, aimed at providing mental, emotional and behavioural support for school children. More than 240,000 children in 1,310 schools are now part of the program.

An additional motivation for philanthropy in China draws on traditional filial piety and loyalty to one’s hometown. For instance, philanthropist and founder of Midea Group, He Xianjiang, spoke about his intention to build a state-of-the-art hospital in his family’s hometown. He said, ‘[I want to] give back to society this way and do one more meaningful thing for my hometown and society.’ This sentiment was expressed in almost every interview we did for our study.

When looking at Chinese philanthropy, it is helpful to understand the parameters in which the donor is operating. Alignment with government is critical to operating in China.

In the next article on the theme of environmental philanthropy, we look at the unique features of this relatively new area of focus in China’s philanthropic landscape.

Ruth A. Shapiro, PhD, is Co-Founder and CEO of the Centre for Asian Philanthropy and Society (CAPS). And Vincent Cheng is Research Manager at CAPS.

Alliance Magazine is collaborating with CAPS to publish a series of four articles about ‘Philanthropy with Chinese Characteristics’ over the next several months. Drawing upon the insights of CAPS’ latest China Issue Guide Series, each piece will dive into the features of Chinese philanthropy addressing health, environment, education, and poverty alleviation. Read the full report.

Comments (0)